Busting five myths about natural resources

Misconceptions about one of the most serious and widely discussed topics on the global agenda are at the heart of the World Economic Forum’s recent report, The Future Availability of Natural Resources: A New Paradigm for Global Resource Availability. This exploration of which resources will be available and for how long – involving over 300 experts and decision-makers – has uncovered that too often we rely on assumptions and clichés when thinking about supply, demand and the broader future of water, food, energy and mineral resources.

In analysing different perspectives on the availability of natural resources in the medium term (until the year 2035) we’ve drawn together five key insights.

Myth 1: “Resource availability is all about physical supply.”

Reality: What matters most are evolutions in technology, preferences, policies and prices.

Stakeholders tend to overemphasize the biophysical availability of natural resources, in the form of known reserves. But the supply of a particular resource is not determined only – or even primarily – by the existence of physical stocks; having a resource in the ground is only where the story starts.

What matters most in a 20-year timeframe is the “market” or “end-user” availability of a given resource; something that cannot be predicted by dividing known stocks by existing demand. Indeed, the impact of evolutions in technology, preferences, policies and prices are all critical inputs when it comes to projecting estimates of supply and demand. Yet major resource estimates (and the models they rely on) regularly underestimate these evolutions, or simply assume that they are constant.

In terms of resource demand, for example, consumer preferences and behaviours vary widely across countries and cultures. There are even differences between countries at the same level of economic development: the rates of growth in Japan and the US, for example, are miles apart.

Myth 2: “Population growth will cause the world to run out of resources.”

Reality: Economic growth and development are the major drivers of future resource demand.

Many commentators see the world’s growing population as a key challenge to future resources. However, contrary to popular perceptions, economic growth and development are far more significant in driving resource demand.

Over the next 20 years, estimates based on trending energy and population demand indicate that China, for example, will contribute only 4% of the world’s expected population growth, but will account for almost 40% of additional energy demand.

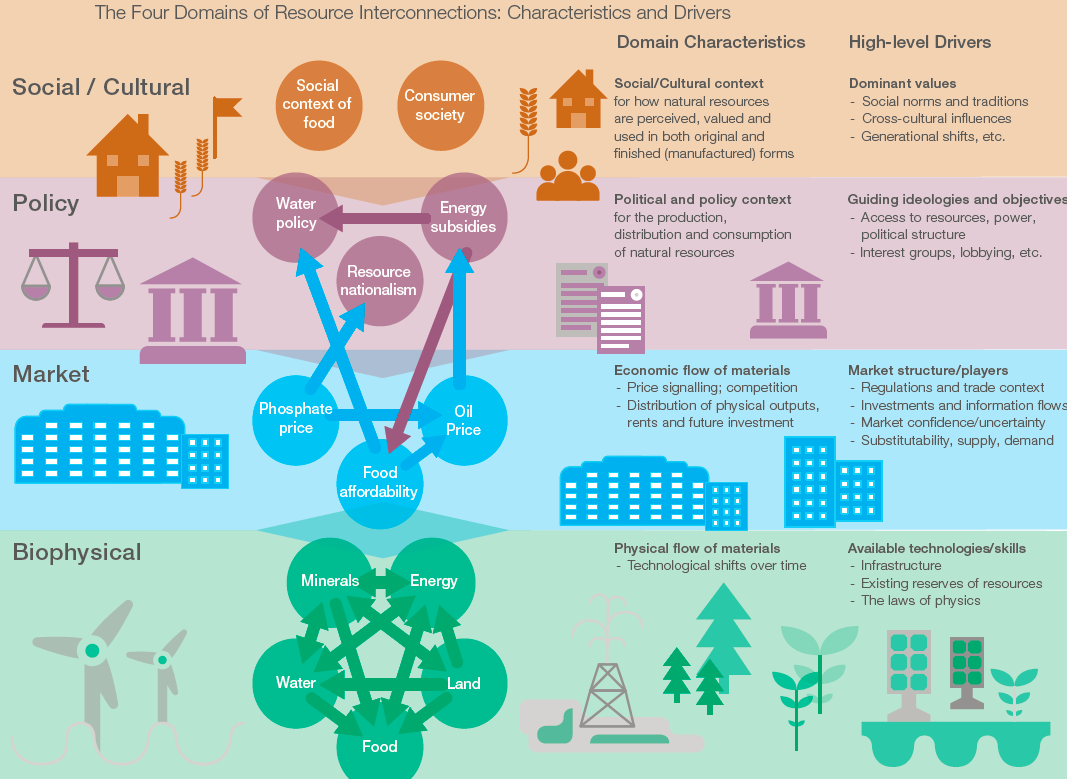

Myth 3: “Interconnections between different natural resources occur primarily at a biophysical level.”

Reality: Economic, political and social interconnections between resources also play an increasingly important role in their availability.

Great efforts have been made over the past few years to better understand the tight connections that bind natural resources to one another. Think of early biofuels, for example, which require vast swaths of land and often create a trade-off with food production to create energy. The “water-food-energy nexus”, once a niche concept, is now an increasingly common catchphrase for these connections. Yet we are still oblivious to the economic, political and social interconnections between resources. These are multiplying and will increasingly influence resource availability, to both positive and negative effect.

Cultural and legal factors play their part: there is greater concern about environmental hazards, for example. In the US, unlike in Europe, landowners have the right to sell underground resources, such as minerals. The shale gas revolution taking place in the US has proven difficult to replicate in European countries. Given the role of the shale-gas boom in the rebirth of US energy-intensive manufacturing, the economic repercussions of European nations not being able to follow suit could bring to light close interconnections at all levels –cultural, legal, political, economic and technological.

Myth 4: “Social justice is an important but auxiliary concern in ensuring supply of resources.”

Reality: Taking into account social justice and fairness of access is central to ensuring stable production and distribution of resources.

Definitions of natural-resource availability often fail to consider the ways in which resources are distributed, both among countries and among individuals within countries. Yet in a practical sense, what matters is not just whether there are enough resources “overall”. It also matters whether everyone within a given community has access to them, or if there are cases of serious disenfranchisement. If access is found to be lacking, disproportionate destabilizing effects can be felt throughout the system due to tight interconnections on multiple levels. It is not just a matter of morals to ensure that there is social justice in the distribution of natural resources, it’s also smart business.

Myth 5: “Choosing between resource availability and environmental conservation is a Sophie’s choice.”

Reality: Resources and the environment are two sides of the same coin, but that also means they may be solved hand in hand.

While most people understand that both natural-resource availability and environmental conservation are critical, few are fully aware that the issues are two sides of the same coin. In fact, natural resource availability and environmental sustainability go hand in hand; they are tied together in an intimate feedback loop. If the environment is degraded, as it is being degraded today, resources we need for the future will be destroyed. Conversely, if we mismanage our resource use, environmental degradation will inevitably result. We are currently locked in a vicious circle, but the important takeaway is that this cycle can be reversed.

As it states in the report’s conclusion, the world already possesses the necessary technical knowledge to service resource needs for the near future. Unlocking the potential of this knowledge, however, will require stakeholders to build a shared and holistic picture of the factors driving tomorrow’s resource availability. Only by developing such a shared worldview will we be able, effectively and collaboratively, to work towards better resource management.

Follow the Strategic Foresight team

Twitter @WEForesight

Authors: Kristel Van der Elst is senior director and head of the World Economic Forum’s Strategic Foresight practice, where Andrew D. Bishop is a senior manager. Nicholas Davis is the director and head of Europe at the World Economic Forum.

Image: The colors of Fall can be seen reflected in a waterfall along the Blackberry River in Canaan, Connecticut REUTERS/Jessica Rinaldi

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.