How researchers can analyse the causes of cancer

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Emerging Technologies

In the majority of cases, the onset of cancer is characterised by a minor change in a person’s genetic material. A cell’s DNA mutates in a particular area to the extent that the cell no longer divides in a controlled manner, but begins to grow uncontrollably. In many cases, this type of genetic mutation involves chemical changes to individual building blocks of DNA. These changes are induced by smoking tobacco and consuming foods such as cured meats. This is because the contents of these materials can chemically react with and change building blocks of cellular DNA, thereby creating DNA adducts. Up to now, scientists have been able to determine whether gene samples contain adducts and if so, how many. However, the procedure is laborious and finding out exactly where a building block in the genetic code has been altered into an adduct has not been possible.

Researchers from the team led by Shana Sturla, professor of Food and Nutrition Toxicology, have succeeded for the first time in amplifying gene samples containing DNA adducts while retaining references to these adducts. This type of amplification is a prerequisite for the majority of technologies used by researchers to determine a gene’s DNA sequence. In the future, it may therefore be possible to expand DNA sequencing from the four basic DNA building blocks to include adducts. “The scientific community would have an important tool for making a detailed analysis of the molecular mechanisms involved in the initiation of cancer and the corresponding risk factors,” says Sturla.

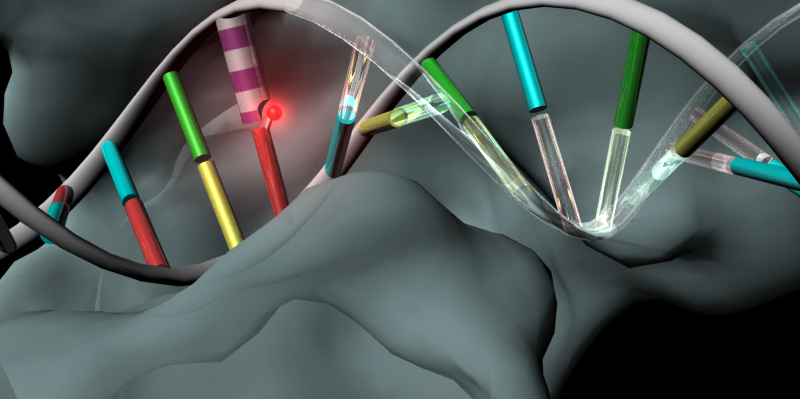

Genes including altered DNA building blocks (glowing in red) can be amplified thanks to an artificial DNA building block created by ETH researchers (striped). (Illustration: O’Reilly Science Art)

Genes including altered DNA building blocks (glowing in red) can be amplified thanks to an artificial DNA building block created by ETH researchers (striped). (Illustration: O’Reilly Science Art)

Artificial counterpart found

The researchers focused their efforts on a specific, typical DNA adduct, an alkylguanine called O-6-benzylguanine. They recreated an enzyme reaction in a test tube to obtain a negative copy of the genetic material – analogous to how DNA is replicated naturally in cells. The scientists first had to find an artificial counterpart of the alkylguanine to be incorporated into the negative copy in its position – due to the fact that nature produces molecular counterparts to the basic DNA building blocks, but not to DNA adducts. This is why replicating genes usually leads to copy errors (or mutations) when adducts are present.

The ETH researchers produced several artificial derivatives of the basic DNA building blocks in the laboratory and tested them as potential counterparts to the alkylguanine. One proved particularly suitable. The researchers were then able to produce a negative copy of a gene containing the alkylguanine.

The aim of the work carried out by Sturla and her colleagues was to demonstrate that it is feasible to amplify genes even when adducts are present. It should now be possible for researchers to find artificial counterparts to other adducts using the same method. As the ETH Professor points out, this means that altered genes could be amplified in the future and their sequences more easily ascertained. In 2010, Shana Sturla was awarded a five-year ERC Starting Grant from the European Research Council. The current project was partly financed by this award.

Literature reference

Wyss LA, Nilforoushan A, Eichenseher F, Suter U, Blatter N, Marx A, Sturla SJ: Specific incorporation of an artificial nucleotide opposite a mutagenic DNA adduct by a DNA polymerase. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 9 December 2014, doi:10.1021/ja5100542

This article is published in collaboration with ETH Zurich. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with Forum:Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Fabio Bergamin studied Biotechnology in Basel and Strasbourg and received a Ph.D. from the University of Bern in Immunology.

Image: A radiologist examines breast X-rays after a cancer prevention medical check-up at the Ambroise Pare hospital in Marseille, southern France, on April 3, 2008. REUTERS/Jean-Paul Pelissier.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Emerging TechnologiesSee all

Sebastian Buckup

April 19, 2024

Juliana Guaqueta Ospina

April 11, 2024

Nikolai Khlystov and Gayle Markovitz

April 8, 2024

Simon Torkington

April 8, 2024

Victoria Masterson

April 4, 2024