The paradox of technology’s impact on inequality in Africa

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Africa

Thirty years ago, a UN commission published the Maitland Report, proposing that, by the early 21st century, every individual on the planet should “be within easy reach of a telephone” given its economic benefits. That was interpreted as being within a one-day walk of a phone. Anyone suggesting back then that over 90% of the global population would be covered by mobile cellular signals, and over half of the world’s population would have a phone in their pocket, would have been labelled a crazy optimist. Yet, today it’s all about high-speed broadband connections, which total over 3.4 billion as of 2014 ‒ nearly half of the world’s population.

This year’s Global Information Technology Report, and chapter 1.2 in particular, details the history of information and communications technologies (ICTs) as a powerful driver of economic growth and reviews the remaining barriers to more inclusive prosperity. The available evidence presents a paradox where ICTs are driving economic growth and decreasing global inequality while, at the same time, contributing to rising within-country income inequality. Leaders gathering this week in Cape Town for the World Economic Forum on Africa, marking 25 years of change on the continent, will debate and detail the role of ICT in driving the next stage of innovative approaches to growth and sustainable development for the region.

For sub-Saharan Africa, the new report highlights the region’s overall stable performance since 2012 in its ICT ecosystem. The report’s Networked Readiness Index (NRI) ‒ a measure of 143 countries on the basis of their ICT environment, readiness, usage and impact ‒ notes that the majority of countries in the region are in the bottom half of the global sample. However, most of these countries have displayed consistent progress either in ranking or in overall score. Six of the region’s countries made the top 100, including Mauritius, Seychelles, South Africa, Rwanda, Kenya and Cape Verde. Ghana just missed the mark at 101st.

South Africa, while dropping in the rankings this year to 75th, maintained its overall score of 4.0. Kenya’s ranking rose six places to 86th and, like South Africa, its score has been slowly improving since 2012. Rwanda improved both its score and its ranking by three positions (83rd) and scored especially well for government usage, ranking 12th worldwide in that dimension. Mauritius, sub-Saharan Africa’s highest-ranked country, not only improved its score, but also rose in the rankings to 45th, breaking into the top half of all NRI-rated countries. Additionally, Lesotho has earned sub-Saharan Africa’s award for most improved in 2015, rising nine spots from its 2014 score to reach 124th.

The performance of the region is noteworthy: on average, sub-Saharan Africa performs better in terms of liberalization than emerging and developing Asia or regions within the Middle East and North Africa. Many sub-Saharan African countries have fully liberalized their ICT markets, and some – including Kenya and Tanzania – are already reaping the benefits of doing so. Increased investments in addition to the introduction of new business models and services represent just a few of the positive side-effects of cultivating a market that is open to digitization.

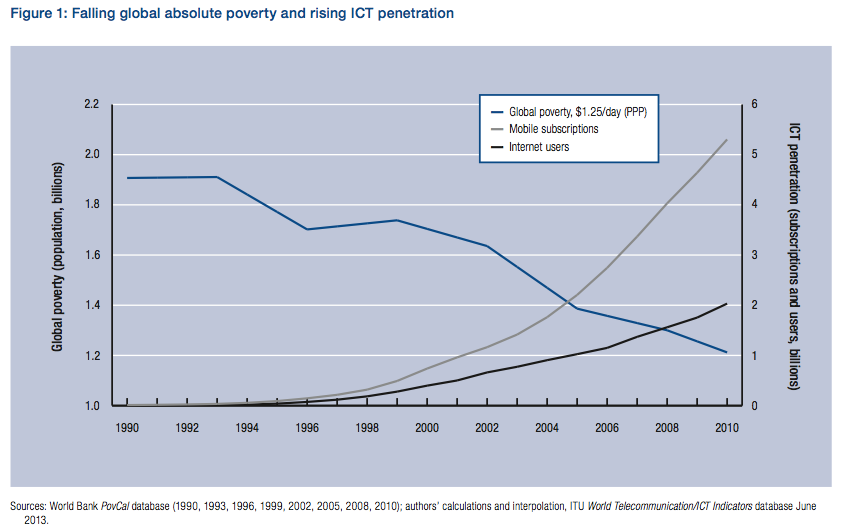

A direct result of ICT adoption is the steady decline in absolute poverty across developing regions. The global extreme poverty rate (those individuals surviving on less than $1.25 per day) dropped from 1.9 billion people in 1981 to 1.3 billion in 2010, according to the World Bank; and extreme poverty rates in developing countries dropped from more than 50% to 21%. This decline in extreme poverty has been driven by long-run economic growth in China and India, recent growth across Africa, and the impact of social programmes in Latin America.

The picture is more mixed, however, when looking at ICTs’ impact on income inequality. At the global level, the latest available data from the World Bank show income inequality (the distribution of income across all people in the world) to be on the decline. The most recent analysis finds that global income inequality has fallen steadily from a Gini coefficient of 72.2 in 1988 to 70.5 in 2008, with the decrease attributed to the large overall income gains of the global median (around the 50th percentile) of the population.

However, the decrease in global income inequality masks the income inequality increases observed within individual countries. Within-country income inequality appears to be rising in many countries, in both the developed and developing world. The reason for this paradox is that, while ICT improves the standard of living for those who adopt it, those who do not adopt and use ICT do not improve their standard of living as fast or as much. One analysis by the International Monetary Fund suggests that technological progress, measured as the share of ICT capital stock, has a statistically significant impact on inequality.

In addition, the full benefit of ICTs has yet to accrue to lower income groups. For example, network effects and externalities that multiply the impacts of ICTs require minimum adoption thresholds before those impacts begin to materialize. One analysis finds a positive impact of 2.8% increase on GDP resulting from a 10% increase in telecommunications infrastructure, but only once a minimum threshold density is reached. In this case, the threshold is at 24% of the population.

In other words, countries will only experience the full growth impacts of ICTs once penetration passes that point. Similarly, a 2009 analysis determined that increasing returns to broadband investment occur when a critical mass of penetration ‒ above 20% (20 subscriptions per 100 people) ‒ is reached.

Evidence from the last two decades demonstrates that ICTs, particularly broadband internet, are income multipliers. At the country level, macroeconomic data links fixed telephony, mobile telephony, internet use and broadband use to GDP growth in a causal relationship across developed and developing countries. And increasing the intensity of data use also drives per capita income growth. This growing body of evidence highlights the fact that we are long past the days of the “Solow paradox” when, in 1987, Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow noted: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

At the microeconomic level, emerging analysis highlights the impact that ICTs can have on driving income growth at the bottom of the economic pyramid. Mobile phones in particular have spread across the developing world and this “mobile miracle” is contributing to income growth as handsets act not only as a communications device for sharing public and private information, but also as educational tools for delivering learning content, and as a financial transfer and savings device.

To counter the disparity in the use of ICTs between lower- and higher-income groups, immediate actions should focus on closing the disparity in ICT adoption/penetration. To ensure that benefits of ICT accrue to lower-income populations, more needs to be done to increase broadband availability and adoption, particularly through policies that achieve universal access, increase affordability, increase digital skills and close the gender gap. These include:

- Focusing public resources and incentives for building broadband internet access out to rural and underserved communities

- Connecting schools and libraries to broadband internet service and ensuring widespread connectivity within schools

- Removing excessive taxation on devices and access, and considering targeted subsidies for certain populations

- Developing robust ICT training curricula and programmes

- Focusing on closing the gender gap in ICTs

The data in this year’s Global Information Technology Report leave no question that the adoption and use of ICTs have a positive effect on income and growth on lower-income countries and populations. However, the challenge to accelerate ICT adoption, particularly among lower-income groups, remains. Combining the positive economic growth impact of ICTs with targeted interventions focusing on alleviating poverty will improve the well-being of citizens everywhere, especially those in absolute poverty at the bottom of the pyramid.

The World Economic Forum on Africa 2015 takes place in Cape Town, South Africa from 3-5 June.

Author: Dr Robert Pepper is Cisco’s Vice-President for Global Technology Policy

Image: A Somali woman talks to her cell-phone outside her house in Mogadishu, November 4, 2009. REUTERS/Feisal Omar

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on AfricaSee all

Efrem Garlando

April 16, 2024

Babajide Oluwase

April 15, 2024

Eliza L. Swedenborg

April 3, 2024

Christiane Zarfl and Rebecca Peters

March 27, 2024

Brian D’Silva and Abir Ibrahim

March 19, 2024