10 years of the flexible Renminbi

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Financial and Monetary Systems

On Thursday July 21, 2005, Australia opened the batting at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London on the way to winning the first Ashes test against England.

Currency traders, however, had to tear themselves away from the action after China’s out-of-the-blue announcement that it would replace its decade-old currency peg with a more flexible exchange rate regime.

The move loosened the renminbi’s strict Rmb8.276-8.28 range against the dollar and from the next day, it was allowed to fluctuate by up to 0.3 per cent against the greenback and by up to 1.5 per cent against other currencies.

Since then, the renminbi has gained about 30 per cent against the dollar in nominal terms, its trading bands have widened and an offshore renminbi market has developed.

What did — and does — it mean?

For China-watchers, the renminbi’s gradual moves towards full convertibility with long pauses along the way have become the classic example of China’s general gradualist approach to economic reform. In other words, while the overall direction of travel is clear, the timing never is.

An internationally-accepted currency would help China shift wealth from its foreign exchange reserves ($3tn and counting) to the private sector. If it became a reserve currency it could lessen the impact of monetary policy of other countries — like the US — on China’s own economy.

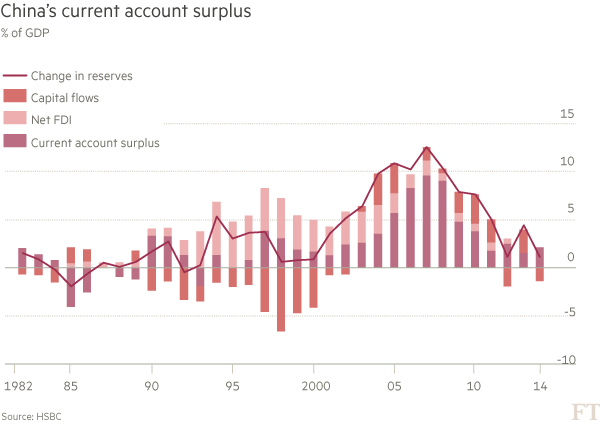

The renminbi’s rise also helped China’s trade surplus to fall, easing tensions with other countries, notably the US, and slowing its accumulation of dollars.

As part of wider economic reforms, future renminbi moves are expected to keep nudging the currency towards full convertibility.

“To that end, we expect restrictions on firms’ abilities to make FX transactions will be loosened further, while individuals’ FX quotas will also be increased or maybe even removed,” says Qu Hongbin, chief China economist for HSBC.

Who gains?

Banks with strong Hong Kong businesses, for one. The likes of HSBC and Standard Chartered have been positioning themselves as renminbi leaders, competing to plant flags whenever China allows another product in a new market.

Hong Kong, Singapore and London are the leading offshore centres but others like Taipei and Seoul are also active.

About Rmb2tn ($327bn) of renminbi has accumulated offshore in the past five years, according to HSBC.

What next?

China’s goal for this year is for the International Monetary Fund to add the renminbi to its so-called special drawing rights basket of currencies that it deems to have reserve status.

The IMF in May declared the renminbi “no longer undervalued” — a key shift in tone — but China’s heavy-handed stock market intervention of the past month has raised fears it could set back SDR acceptance, which is based on a currency being freely usable.

Yet even as Beijing waded into the stock market, it loosened restrictions on foreign investment in its interbank bond markets, allowing central banks, supranational institutions and sovereign wealth funds access to the market without preapproval.

Koon How Heng, an analyst at Credit Suisse, said the move was “yet another sign of commitment” from China to internationalising the renminbi.

“It would appear that the very volatile swings in the onshore equity market over the past few weeks have not deterred the authorities,” he added.

Meanwhile, the renminbi’s use in trade continues to grow and about a quarter of China’s overall trade is now settled in its own currency. The growing use of the renminbi in real business transactions is a key sign that its internationalisation is more than just politics.

Other articles from The Financial Times:

China widens foreign access to bond market

New Brics bank in Shanghai to challenge major institutions

China considers options as market dust settles

This article is published in collaboration with The Financial Times. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: The Financial Times covers, comments and analyses the latest UK and international business, finance, economic and political news.

Image: Chinese 100 yuan banknotes are seen in this picture illustration. REUTERS/Jason Lee.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Financial and Monetary SystemsSee all

Lucy Hoffman

April 24, 2024

Michelle Meineke

April 24, 2024

Annamaria Lusardi and Andrea Sticha

April 24, 2024

Emma Charlton

April 24, 2024

Piyachart "Arm" Isarabhakdee

April 23, 2024

Kate Whiting

April 23, 2024