Another reason the Fed might not raise rates

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

United States

Let’s forget about China for a moment.

The turmoil that the world’s second-largest economy has incited in global financial markets has ramped up speculation over when the Federal Reserve will finally raise its target interest rate, with the odds of that happening when the central bank meets next month falling rapidly.

But that doesn’t mean September was a done deal before the latest crisis.

Fed officials have repeatedly pushed out their forecasts for the first rate hike and moved down their expectations of the path of subsequent increases. One of the main culprits? Inflation, or rather a lack thereof.

The central bank has stated that it wants to be “reasonably confident” that inflation is headed back up to its goal of 2 percent before it begins to withdraw its support for the U.S. recovery. But something is always getting in the way — a surge in the dollar, a drop in oil prices, weak productivity.

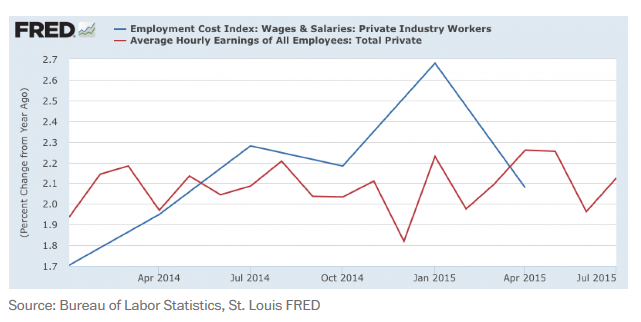

There were glimmers earlier in the year that prices were starting to move back up. Wage growth, in particular, seemed to have some momentum after stagnating for years. Average hourly earnings for private workers rose by 2.3 percent this spring compared to a year ago. Meanwhile, the employment cost index, which tracks how much businesses spend on wages and salaries, saw its biggest year-over-year jump since the Great Recession during the first quarter.

The activity, combined with the strong hiring and a rapidly falling unemployment rate, gave the Fed hope that the economy would be able to withstand the first rate hike in nearly a decade by the end of the year.

In a March speech in California, Fed Chair Janet Yellen laid out a strong case for an interest rate increase this year. She emphasized that monetary policy works with long lags and the dangers of waiting too long to make a move:

I would not consider it prudent to postpone the onset of normalization until we have reached, or are on the verge of reaching, our inflation objective. Doing so would create too great a risk of significantly overshooting both our objectives of maximum sustainable employment and 2 percent inflation, potentially undermining economic growth and employment if the FOMC is subsequently forced to tighten policy markedly or abruptly.

In her remarks, Yellen explicitly stated that a pickup in inflation was not a precondition to a rate hike. But she also said that she would be “uncomfortable” raising the Fed’s target rate if wage growth or inflation were to weaken.

Guess what happened?

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, St. Louis FRED

The employment cost index posted its smallest quarterly gain on record during the spring. The pickup in average hourly earnings turned out to be just another blip. Oil prices resumed their slide. Productivity remains a puzzle.

The standard driver of a Fed rate hike is the appearance of inflation on the horizon. But it would take a telescopic lens to find any sign of it now. And as the threat of inflation becomes increasingly remote, the catalyst for the Fed to act becomes weaker.

It’s worth noting that this is essentially the same position that Chicago Fed President Charles Evans staked out last year: The lack of inflation pressure gives the central bank plenty of room to be patient, even as the unemployment rate continues to fall.

So the Fed was heading into the September meeting with lukewarm arguments on both sides of the coin: Any urgency to act to combat inflation was fading, but a tiny increase in the target rate wasn’t likely to do much harm.

Now add China back to the equation. The uncertainty surrounding the world’s second-largest economy provides the Fed with a good reason to stay the course when it meets next month. And bets are growing that it will wait a while longer.

This article is published in collaboration with Wonkblog. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Ylan Q. Mui is a Reporter in Washington, D.C.

Image: The United States Federal Reserve Board building is shown behind security barriers in Washington. REUTERS/Gary Cameron

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.