How sustainable is global debt?

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Economic Progress

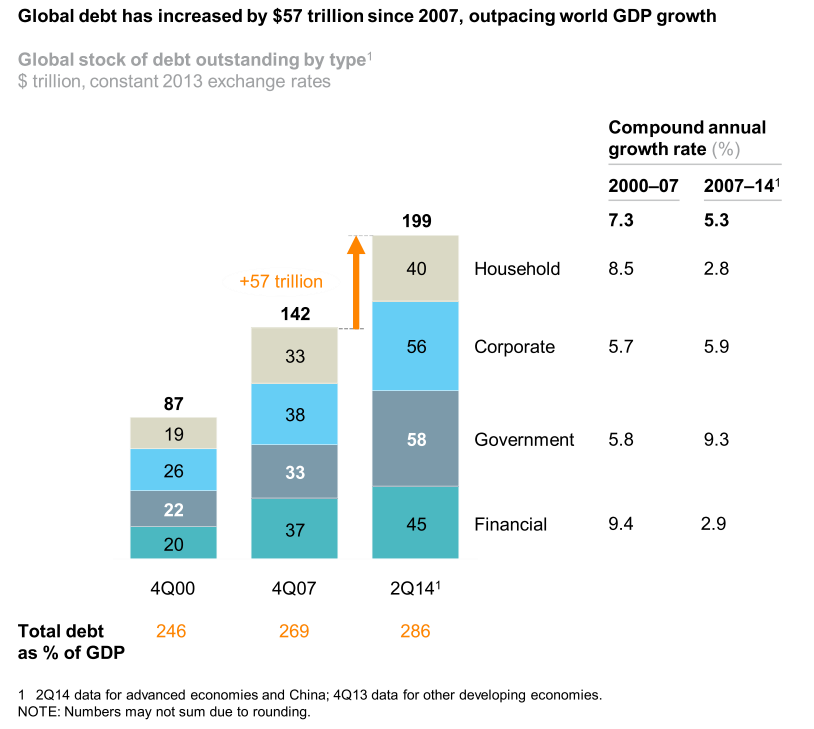

McKinsey published a report titled “debt and (not much) deleveraging”, which raises the point that seven years after the bursting of the global credit bubble, debt continues to grow. In fact, rather than reducing indebtedness, or deleveraging, all major economies today have higher levels of borrowing relative to GDP than they did in 2007. Global debt in these years has grown by $57 trillion, raising the ratio of debt to GDP by 17 percentage points (see chart below). That poses new risks to financial stability and may undermine global economic growth. They conclude that the current solutions for sparking growth or cutting fiscal deficits alone will not be sufficient. New approaches are needed to start deleveraging and to manage and monitor debt. This includes innovations in mortgages and other debt contracts to better share risk; clearer rules for restructuring debt; eliminating tax incentives for debt; and using macroprudential measures to dampen credit booms.

Source: McKinsey

Focusing on the euro area, the Bundesbank reports that credit demand has stabilized since mid 2013, and picked up significantly since autumn 2014. Nevertheless, major country differences remain. Looking at the four biggest members of the Euro area (Germany, France, Italy, Spain), they find that credit growth is driven by a more-or-less advanced economic recovery. However, Spanish and Italian credit growth is weaker compared to the historical trend, while French and German credit growth are more aligned. The factors behind the weak credit performance over the last years are the necessity of the non-financial sector to fix its balance sheet, and the damaged banking sector. On a more positive note, Spanish companies managed to reduce their respective debt overhang since 2012, which is contributing to the strong recovery observed. Moreover, indicators show that the financial fragmentation has been reduced in both countries, but non performing loans are still weighing on the banking sector.

Secular stagnation versus the debt-super-cycle

Kenneth Rogoff argues that excessive debt issue and over-leverage lies behind of what has happened in the past seven years. He believes that the difficulties will end when deleverage has reduced the overhang of risky and underwater debt to a sustainable level.

“some argue that we are living in a world of deficient demand, doomed to decades of secular stagnation. Maybe. But another possibility is that the global economy is in the later stages of a debt “super cycle”, crushed under a burden accumulated over years of lax regulation and financial excess.”

He dismisses the idea of secular stagnation, as it is always very difficult to predict long-run future growth trends, and although there are some headwinds, technological progress seems at least as likely to outperform over the next two decades as it is to exhibit a sharp slowdown. Unlike secular stagnation, a debt supercycle is not forever. After deleveraging and borrowing headwinds subside, expected growth trends might prove higher than simple extrapolations of recent performance might suggest. In this respect, the US appears to be near the tail end of its leverage cycle, Europe is still deleveraging, while China may be nearing the downside of a leverage cycle. Though many factors are at work, the view that we have lived through a debt supercycle, marked by a severe financial crisis, is far more constructive for policy analysis than the view that the world is suffering from long-term secular stagnation due to a chronic shortfall of demand.

Paul Krugman dismisses Rogoff, by stating that he doesn’t address the key point that Larry Summers and others, including him, have made — that even during the era of rapid credit expansion, the economy wasn’t in an inflationary boom and real interest rates were low and trending downward — suggesting that we’re turning into an economy that “needs” bubbles to achieve anything like full employment. More generally, Krugman argues that nobody understands debt: The demands that everyone tighten their belts were based on a misunderstanding of the role debt plays in the economy. You can see that misunderstanding at work every time someone rails against deficits with slogans like “Stop stealing from our kids.” It sounds right, if you don’t think about it: Families who run up debts make themselves poorer, so isn’t that true when we look at overall national debt? No, it isn’t. An indebted family owes money to other people; the world economy as a whole owes money to itself. And while it’s true that countries can borrow from other countries, America has actually been borrowing less from abroad since 2008 than it did before, and Europe is a net lender to the rest of the world. Because debt is money we owe to ourselves, it does not directly make the economy poorer (and paying it off doesn’t make us richer). True, debt can pose a threat to financial stability — but the situation is not improved if efforts to reduce debt end up pushing the economy into deflation and depression.

Debt overhang in the EME

The IMF just published a chapter on corporate leverage in emerging markets, reporting that corporate debt of nonfinancial firms across major emerging market economies quadrupled between 2004 and 2014. The upward trend in recent years naturally raises concerns because many financial crises in emerging markets have been preceded by rapid leverage growth. Firm- and country-specific characteristics in explaining leverage growth have diminished as opposed to the role of global drivers. Leverage has risen in more cyclical sectors, particularly in construction, and is, on average, associated with rising foreign currency exposures. Despite weaker balance sheets, emerging market firms have managed to issue bonds at better terms, with many issuers taking advantage of favorable financial conditions to refinance their debt. To address these issues, monitoring vulnerable and systemically important firms, as well as banks and other sectors closely linked to them, is crucial, and improved data collection is paramount. Also, macro- and microprudential policies could help limit a further buildup of foreign exchange balance sheet exposures and contain excessive increases in corporate leverage. As advanced economies normalize monetary policy, emerging markets should prepare for an increase in corporate failures and, where needed, reform corporate insolvency regimes.

Carmen Reinhart makes the point that emerging markets are rife with symptoms of increasing economic vulnerability, especially when it comes tohidden debts.

“it was not until after the eruption of the 1994-1995 peso crisis that the world learned that Mexico’s private banks had taken on a significant amount of currency risk through off-balance-sheet borrowing (derivatives). Likewise, before the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the IMF and financial markets were unaware that Thailand’s central-bank reserves had been nearly depleted (the $33 billion total that was reported did not account for commitments in forward contracts, which left net reserves of only about $1 billion). And, until Greece’s crisis in 2010, the country’s fiscal deficits and debt burden were thought to be much smaller than they were, thanks to the use of financial derivatives and creative accounting by the Greek government.”

She states that though emerging economies’ debts seem largely moderate by historic standards, it seems likely that they are being underestimated, perhaps by a large margin. If so, the magnitude of the ongoing reversal in capital flows that emerging economies are experiencing may be larger than is generally believed – potentially large enough to trigger a crisis. In this context, keeping track of opaque and evolving financial linkages is more important than ever.

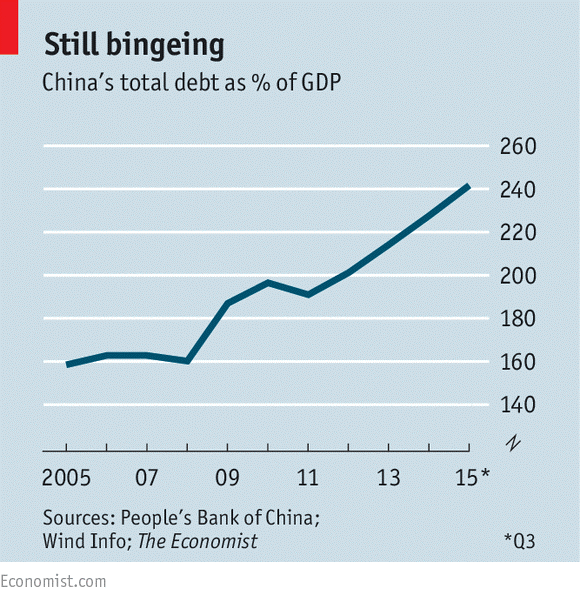

Turning to China, The Economist concludes that after massive credit expansion during the financial crisis, China should have started deleveraging by now. China’s total debt stands at 161 trillion yuan ($25 trillion), more than 240 percent of GDP. However, instead of putting on brakes, chinese banks continue to pump credit into the economy and the authorities are disinclined to address the issue fearing credit contraction. Continued borrowing and rapid increase in debt despite the cooling economy is partly explained by the fact that the biggest debtors are state-owned firms and biggest creditors are state-owned banks. As such, some argue that an acute crisis can be avoided by rolling over bad loans when they are due or abstain from calling them in. Avoiding an acute crisis doesn’t mean that the economy could be spared from a chronic ailment, when even more credit will be needed to sustain growth. To address its debt problem, China used monetary easing and a giant bond swap programme for local governments to reduce debt servicing costs. It isn’t too late to address the country’s debt problem still, however, until then the mountain of debt is expected to grow (see chart below).

Lisa Abramowicz reports further on the Chinese debt bubble and writes that despite an overvalued real estate market and slowing growth in the Chinese economy debt buyers’ appetite for dollar denominated Chinese junk bonds is not waning. There has been surprising market gains of up to 9 percent on a dollar-denominated bonds sold by deeply indebted Chinese property companies, in contrast to falling returns of U.S. high-yield bonds. Debt repayment of 12 billion USD is due this year and there has been numerous insolvencies already, but the investors are standing firm despite the looming property bubble and the clear message from China that it is not going to prop up borrowers headed for bankruptcy.

How to get out of it?

The Geneva Report on the World economy looks into the deleveraging issue and finds that global debt-to-GDP is breaking new highs in ways that hinder recovery in mature economies and threaten new crisis in emerging nations – especially China. The report warns of a “poisonous combination of high and rising global debt and slowing nominal GDP, driven by both slowing real growth and falling inflation”. The policy requirements for successful exit from a leverage trap are much broader than the appropriate conduct of monetary policy. The report also argues that – given the risks and costs associated with excessive leverage – more needs to be done to improve the resilience of macro-financial frameworks to debt shocks and to discourage excessive debt accumulation. Finally, it advocates enhanced international policy cooperation in addressing excessive global leverage.

Dieter Wermuth in der Herdentrieb writes that looking ahead, interest rates will stay low for a long time, as the debt overhang is weighing on inflation. Globally speaking, the attempts by households, companies, governments and banks to fix their balance sheets (meaning to reduce their respective debt overhangs and increase their creditworthiness) translate into lower capacity utilisation. This can only mean that it will not be easy to increase prices and wages in the usual way. He states that there is arguably no alternative to the expansionary monetary policy, including negative deposit rates and expanding central bank balance sheets. However, if deflationary tendencies remain,further steps towards helicopter money might have to be taken, until a general inflation rate of 2% is again considered as normal.

Adair Turner states that we are caught in a trap where debt burdens do not fall, but simply shift among sectors and countries, and where monetary policies alone are inadequate to stimulate global demand, rather than merely redistribute it. More radical policies – such as major debt write-downs or increased fiscal deficits financed by permanent monetization – will be required to increase global demand, rather than simply shift it around.

This article was originally published by Bruegel, the Brussels-based think tank. Read the article on their website here. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Uuriintuya Batsaikhan works as a Research Assistant in the area of European and Global Macroeconomics and Governance. Pia Hüttl is an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel.

Image: A man walks past buildings at a central business district. REUTERS/Nicky Loh.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Emma Charlton

April 24, 2024

Piyachart "Arm" Isarabhakdee

April 23, 2024

Pooja Chhabria and Kate Whiting

April 23, 2024

Pedro Conceição

April 22, 2024

Joe Myers

April 19, 2024

Joe Myers

April 12, 2024