Why the EU needs macro-prudential policies

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

European Union

This article was originally published by Bruegel, the Brussels-based think tank. Read the article on their website here.

The original design of EMU did not include tools to prevent (or deal with) non-fiscal imbalances, and financial instability was not perceived as a significant risk. Ex post, this view proved short sighted as cross-border capital flows became highly de-stabilizing. In light of this lesson, the set-up of an effective macro-prudential framework appears especially important for the future of the euro area, especially in the current low rate environment.

In a recently published paper, I show that the set up of effective macro-prudential policy in the Euro area faces special challenges due to two facts.

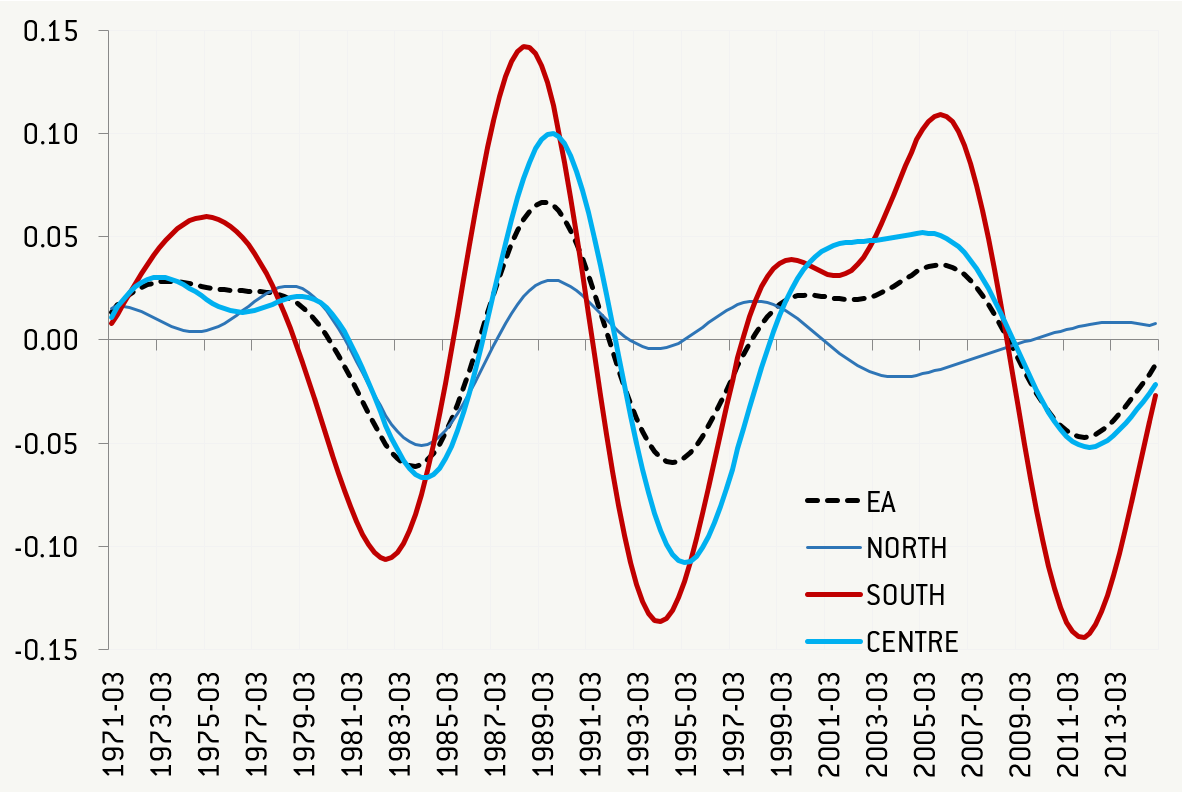

First, over the pre-crisis decade, monetary policy unification and the convergence of interest rates resulted into diversified credit developments across countries, which in turn translated into significant divergence of financial cycles at the country level (figure 1). While the financial cycle of the euro area as a whole was ‘well-behaved’, fluctuating very moderately, individual countries’ positions diverged substantially within the euro area. For Northern countries, the introduction of the euro seems to have marked the turn of the cycle into a contraction phase that lasted till very recently. For countries in the South the opposite happened, and currency unification seems to be associated with the start of a big expansion. France and Italy experienced more moderate fluctuations and remained closely aligned with the euro-area cycle. The macroeconomic counterpart of this was the dis-anchoring of savings and investment as mirrored in the build-up of macroeconomic external imbalances

Figure 1 Financial Cycle: principal component of cycles in real house prices and credit

Source: author’s calculations based on data from BIS; National Sources; IMF; AMECO; OECD.

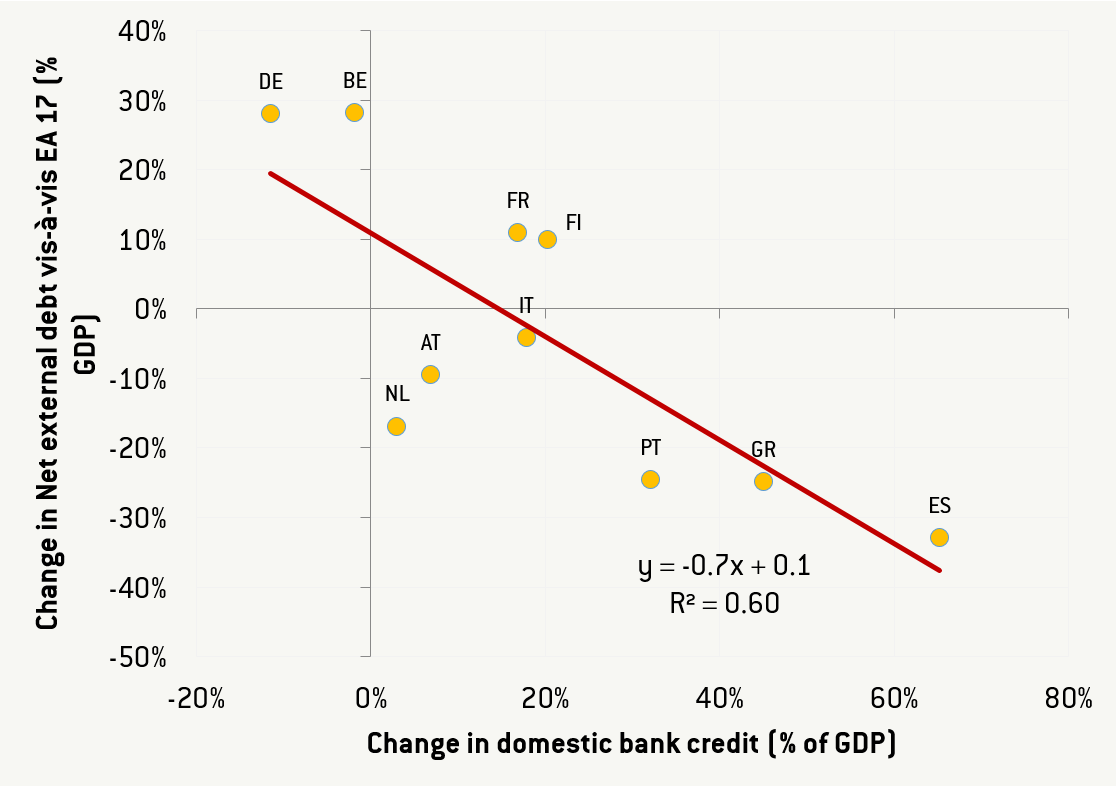

Second, the divergence in financial cycles is deeply rooted in the financial integration that followed the unification of monetary policy. The rapid convergence of interest rates fuelled a credit demand boom in the South. At the same time, banks became able to meet this higher credit demand thanks to increased cross-border banking flows within the euro area, which were facilitated by the currency union. As a result, the divergence in financial cycles at the country level was very strongly correlated with cross-border debt flows, and especially with the intra-euro area component of these flows (figure 2).

Figure 2 pre-crisis correlation between change in domestic credit and change in Net external debt position vis-à-vis other EA countries (2003-2008)

Source: author’s calculations based on data Hobza & Zeugner (2014), BIS, AMECO

In light of this evidence, macro-prudential policy in the euro area faces the task of resolving two (potentially conflicting) goals:

- Deal in an effective way with potentially divergent financial cycles across countries, preventing the build-up of risks to financial stability from underlying domestic imbalances;

- Cater for the cross-border implications of macro-prudential policy in a monetary union, where a high degree of financial integration might induce potential cross-country spillovers from domestic policies, which domestic authorities in turn would have little incentive to internalise

Financial cycles’ heterogeneity implies that macro-prudential policy will need to cater for country specificities, something that monetary policy cannot do. Yet financial stability in a monetary union is a supra-national issue: cross-country financial spillovers can be especially strong and national authorities would have little incentive to internalise them.

The current framework for macro-prudential policy in the euro area is unfit to deal effectively with the special challenges that macro-prudential policy presents in the context of a heterogeneous monetary union. The euro area’s macro-prudential system is currently a two-tier system in which national authorities and the ECB have certain tools governed in a complex relationship. Coordination problems are potentially very relevant, as is the risk of inaction by national authorities because of the political sensitivity of these tools.

There is a strong rationale for entrusting the ECB with stronger macro-prudential powers, making it the prime actor in macro-prudential policymaking, responsible for consistent and coherent application (including internalising cross-border effects), with appropriate divergences catering for national differences in financial conditions.

While the SSM has been given potentially relevant new competences, its effectiveness is limited by the fact that it cannot directly use borrower-based macro-prudential tools (which could be especially relevant in the EMU case), because these are not included in the EU legislation (i.e. CRR/CRD IV). This should be changed.

Finally, the close link between domestic financial cycles and intra-euro area capital flows raises the question of whether macro-prudential policy in the euro area would be compatible with free flows of capital. Before the crisis, intra-euro area debt flows played a major role in shaping the evolution of domestic financial cycles. But members of the currency union in principle cannot impose direct limits/controls on the flow of capital, to curb their domestic credit cycle.

In light of this, an especially important role could be played by the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP), established in 2011 to monitor and deal with excessive macroeconomic imbalances in euro-area member states. The macroeconomic counterpart of financial cycle divergence has been the build-up of significant macroeconomic imbalances. This creates a foundation for significant synergies between the MIP and macro-prudential policy. Many of the macroeconomic variables that form the MIP’s ‘scoreboard’ for assessing the existence of excessive imbalances are also important in the context of macro-prudential early warning. If effectively run, the MIP can potentially tackle the underlying macroeconomic drivers of the financial cycle in a pre-emptive way, and ease some of the hurdles that the ECB could face in implementing effective macro-prudential policy while remaining consistent with the very essence of a monetary union.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Silvia Merler is an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel.

Image: A Euro is shown close-up. REUTERS.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on European UnionSee all

Kimberley Botwright and Spencer Feingold

March 27, 2024

Simon Torkington

February 8, 2024

Mirek Dušek and Andrew Caruana Galizia

January 17, 2024