Can education beat inequality?

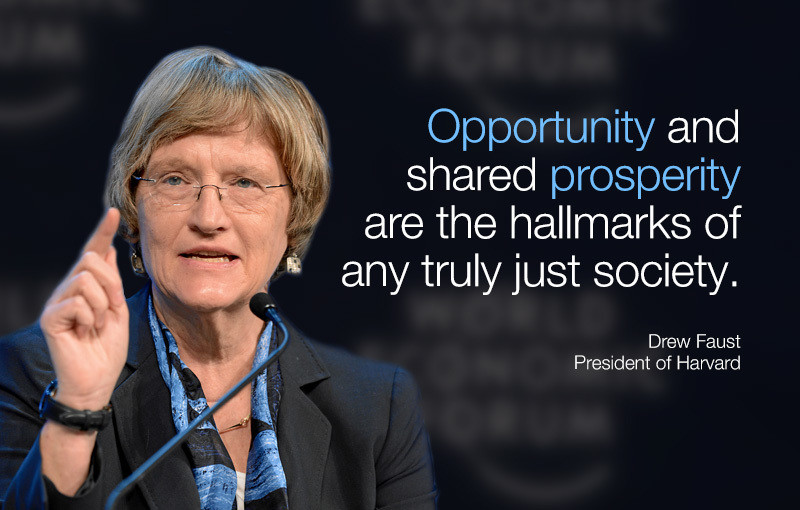

"Addressing inequality requires far more than educating the relatively small share of the total population that we welcome to our campuses each year." Image: REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Education

This year’s World Economic Forum challenges participants to consider and assess the “Fourth Industrial Revolution,” an era of sweeping and rapid technological advances that will disrupt industries and change the future in ways that none of us can predict. What is predictable, however, is that inequality will continue to cast a long shadow on humanity’s progress unless we choose to act.

What role does higher education have to play in ensuring that more individuals are prepared to reap the benefits of the coming age? Knowledge is — and will remain — the most powerful currency, and economic mobility continues to be contingent, in large part, on access to quality education.

Universities expand opportunity and prepare young people for meaningful engagement with their work and with the world. Students encounter points of view and ways of thinking that may be completely foreign to them—and learn to situate their own lives in a broader context as a result. They develop habits of mind that privilege flexibility and resilience, and they graduate with economic advantages that persist throughout their lifetimes.

But confronting and addressing inequality requires far more than educating the relatively small share of the total population that we welcome to our campuses each year. The relatively recent proliferation of online learning opportunities has enabled universities to reach people around the world in ways that would have been unimaginable just a few years ago. Some six million students have enrolled in more than 650 courses provided by edX, a platform co-founded by Harvard and MIT, and they represent just a fraction of individuals who have discovered communities of like-minded learners online. These efforts do more than share knowledge far beyond our campuses. They encourage and test new approaches and methods, and they create unprecedented amounts of data that are shedding light on the most effective methods of teaching and learning.

The scholarship of inequality

Universities are also drivers of research that yields deeper understandings of the mechanisms that perpetuate a poverty of opportunity and the ways in which they are entangled and entrenched.

Scholarship related to inequality is extraordinarily diverse. It explores disparities that touch every dimension of people’s lives, from their preschools to their paychecks to their prognoses. How do the circumstances of a person’s birth affect economic mobility? What causes differences in educational achievement or starting salaries or life expectancies? Who is imprisoned and who is empowered? The answers to these complex questions cut across economics, education, government, law, philosophy, public health, and public policy, and universities are especially well suited to convene experts and practitioners who bring complementary perspectives to the conversation.

Higher education—and the knowledge it produces and advances—can have an extraordinary impact not just on what we know but also on what we do. In the United States, for example, the communication and adoption of best practices among healthcare providers could help to improve outcomes for all patients. A thoughtful reconsideration of sentencing laws and a renewed focus on community engagement and crime prevention could change the nation’s criminal justice system from the inside out. And the development of high-quality education could close achievement gaps—important work being advanced by the Harvard Education Innovation Laboratory as it untangles the relationship between race and unequal education outcomes.

Other efforts develop interventions deployed halfway around the world. Projects to incentivize education in Africa, Asia, and Latin America are encouraging better attendance and performance among schoolchildren. Researchers affiliated with the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership recently revealed that secondary schooling helps to reduce the risk of HIV infection, especially among girls.

“What is fair? How should we treat one another?”

Revolutions — industrial and otherwise — change dramatically the ways in which people understand themselves and their place in the world, and a full consideration of inequality necessarily addresses the meaning of life as well as the means of living. What is fair? How should we treat one another? Why should we work towards the common good? On these and other questions, we must look to the past at least as often as we consider the present and the future.

Here, the humanities hold particular sway. In anthropology and history, for instance, we learn that societies are and have been different across space and time, and that the world has been different and will be different again. These and other fields and disciplines cultivate and refine the ability to recognize and articulate difference, and they are crucial to conversations about where humanity ought to go—and why.

A recent survey conducted by the Harvard Business School identified shared prosperity as “a hallmark of any truly competitive economy.” Opportunity and shared prosperity are the hallmarks of any truly just society. Universities will continue to make important contributions to this goal through the students they educate, the knowledge they produce, and the work and partnerships they support. Stepping out of inequality’s shadow is essential if we hope to master the Fourth Industrial Revolution—and to realize the potential of this remarkable moment in our history.

Author: Drew Faust is the President of Harvard and the Lincoln Professor of History. She is participating in the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on EducationSee all

Natalia Kucirkova

April 17, 2024

Morgan Camp

April 9, 2024

Scott Doughman

March 12, 2024

Genesis Elhussein and Julia Hakspiel

March 1, 2024

Jane Mann

February 28, 2024

Malvika Bhagwat

February 26, 2024