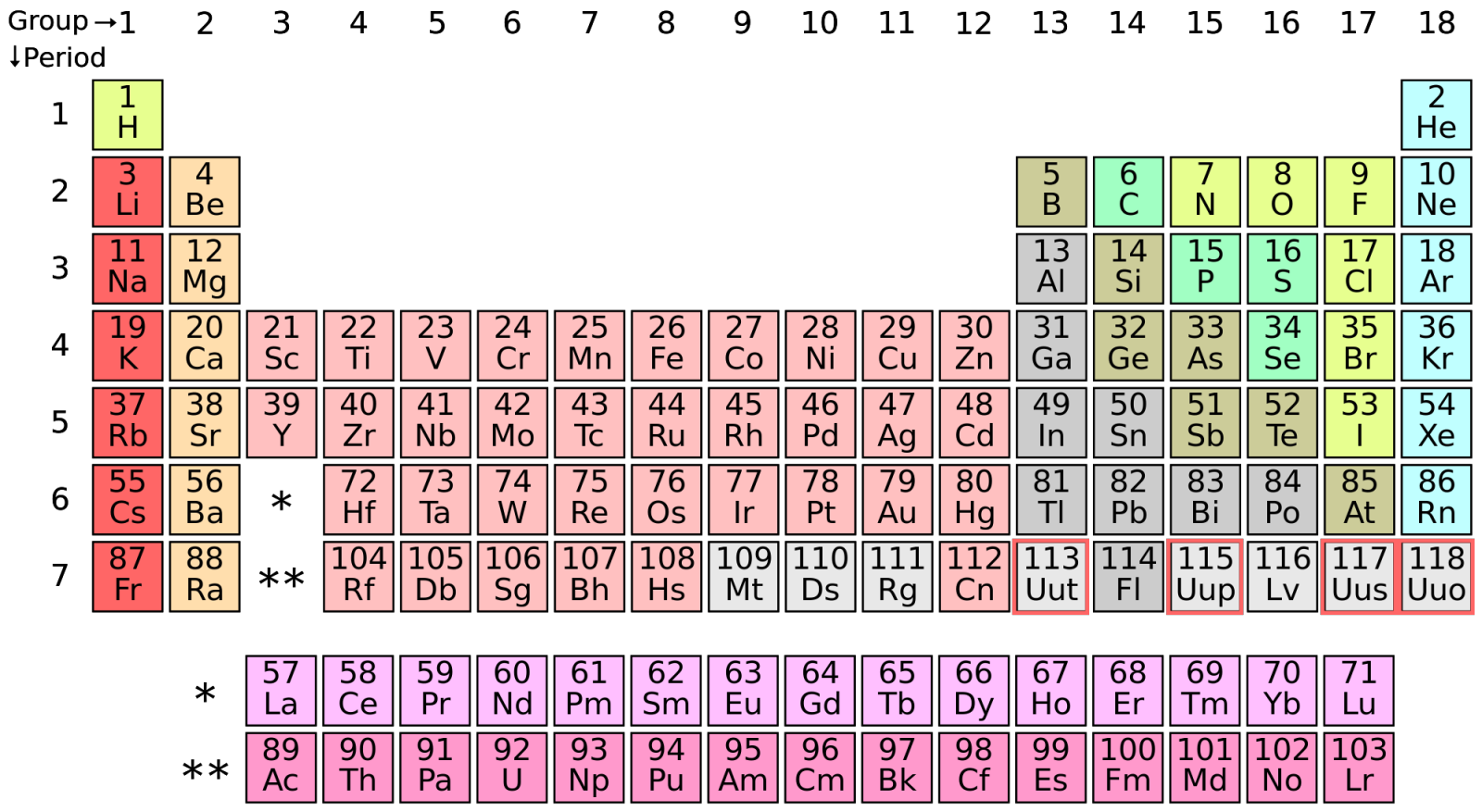

The periodic table gets 4 new elements

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

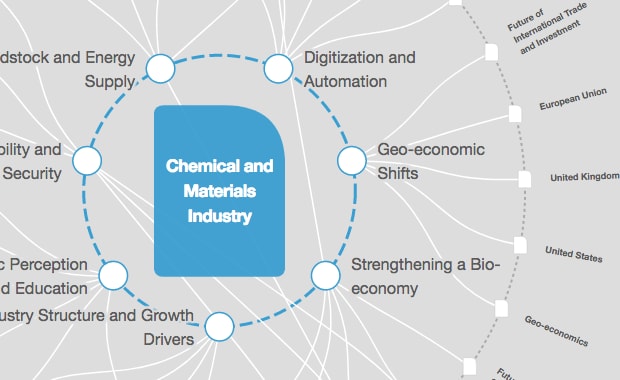

Chemical and Advanced Materials

This article is published in collaboration with Quartz.

If science has an iconic image, it is that of the periodic table of elements.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Akshat Rathi is a reporter for Quartz in London.

Image: A sign showing titanium on the periodic table of elements is seen at the Nobel Biocare manufacturing facility in Yorba Linda, California. REUTERS/Mike Blake.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Industries in DepthSee all

Abhay Pareek and Drishti Kumar

April 23, 2024

Charlotte Edmond

April 11, 2024

Victoria Masterson

April 5, 2024

Douglas Broom

April 3, 2024

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

March 28, 2024