What is the fourth industrial revolution?

A new era is beginning that builds and extends the impact of digitization in unanticipated ways Image: REUTERS/Reinhard Krause

Nicholas Davis

Professor of Practice, Thunderbird School of Global Management and Visiting Professor in Cybersecurity, UCL Department of Science, Technology, Engineering and Public PolicyAre the technologies that surround us tools that we can identify, grasp and consciously use to improve our lives? Or are they more than that: powerful objects and enablers that influence our perception of the world, change our behaviour and affect what it means to be human?

Technologies are emerging and affecting our lives in ways that indicate we are at the beginning of a Fourth Industrial Revolution, a new era that builds and extends the impact of digitization in new and unanticipated ways. It is therefore worthwhile taking some time to consider exactly what kind of shifts we are experiencing and how we might, collectively and individually, ensure that it creates benefits for the many, rather than the few.

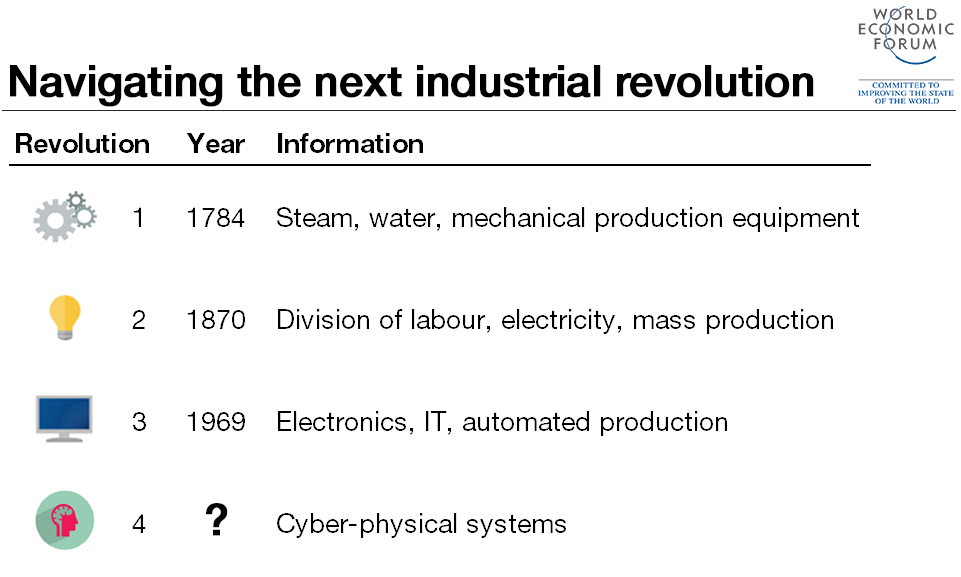

When were the other industrial revolutions?

The First Industrial Revolution is widely taken to be the shift from our reliance on animals, human effort and biomass as primary sources of energy to the use of fossil fuels and the mechanical power this enabled. The Second Industrial Revolution occurred between the end of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century, and brought major breakthroughs in the form of electricity distribution, both wireless and wired communication, the synthesis of ammonia and new forms of power generation. The Third Industrial Revolution began in the 1950s with the development of digital systems, communication and rapid advances in computing power, which have enabled new ways of generating, processing and sharing information.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution can be described as the advent of “cyber-physical systems” involving entirely new capabilities for people and machines. While these capabilities are reliant on the technologies and infrastructure of the Third Industrial Revolution, the Fourth Industrial Revolution represents entirely new ways in which technology becomes embedded within societies and even our human bodies. Examples include genome editing, new forms of machine intelligence, breakthrough materials and approaches to governance that rely on cryptographic methods such as the blockchain.

As the novelist William Gibson famously said: “The future is already here – it's just not very evenly distributed.” Indeed, in many parts of the world aspects of the Second and Third Industrial Revolutions have yet to be experienced, complicated by the fact that new technologies are in some cases able to “leapfrog” older ones. As the United Nations pointed out in 2013, more people in the world have access to a mobile phone than basic sanitation. In the same way, the Fourth Industrial Revolution is beginning to emerge at the same time that the third, digital revolution is spreading and maturing across countries and organizations.

The complexity of these technologies and their emergent nature makes many aspects of the Fourth Industrial Revolution feel unfamiliar and, to many, threatening. We should therefore remember that all industrial revolutions are ultimately driven by the individual and collective choices of people. And it is not just the choices of the researchers, inventors and designers developing the underlying technologies that matter, but even more importantly those of investors, consumers, regulators and citizens who adopt and employ these technologies in daily life.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution may look and feel like an exogenous force with the power of a tsunami, but in reality, it is a reflection of our desires and choices. At the heart of discussions around emerging technologies there is a critical and central question: what do we want these technologies to deliver for us?

What is the potential impact?

Every period of upheaval has winners and losers. And the technologies and systems involved in this latest revolution mean that individuals and groups could win – or lose – a lot. As Schwab says: “There has never been a time of greater promise, or one of greater potential peril.”

While the fact that we are still at the beginning of this revolution means that it is impossible to know the precise impact on different groups, there are three big areas of concern: inequality, security and identity.

1. Inequality

The richest 1% of the population now owns half of all household wealth, according to Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report 2015. Oxfam’s new report presents an even more dramatic concentration of assets, finding that 62 individuals controlled more assets than the poorer 3.6 billion people combined, half the world’s population. This is stunning gap – particularly given that researchers such as Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett have found that unequal societies tend to be more violent, have higher numbers of people in prison, experience greater levels of mental illness and have lower life expectancies and lower levels of trust.

History indicates that consumers tend to gain a lot from industrial revolutions as the cost of goods falls while quality increases, and it seems this is holding true for the latest. Both the Third and Fourth Industrial Revolutions are making possible products and services that increase the efficiency and enjoyability of our lives, while also reducing costs. Organizing transport, booking restaurants, buying groceries and other goods, making payments, listening to music, reading books or watching films – these tasks can now be done instantly, at any time and in almost any place. As Schwab puts it: “The benefits of technology for all of us who consume are incontrovertible.”

But what if these benefits fail to contribute materially to broad-based economic growth? Will everyone truly be able to access, afford and enjoy these innovations?

An important potential driver of increased inequality is our reliance on digital markets. As Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee point out in The Second Machine Age, globally connected digital platforms tend to grant outsized rewards to a small number of star products and services, which are in turn able to be delivered at almost zero marginal cost. In addition, the dominance of digital platforms themselves, given their power, influence and profitability, is concerning to many, including the European Commission. Research shows that in 2013, 14 of the top 30 brands were platform-oriented companies.

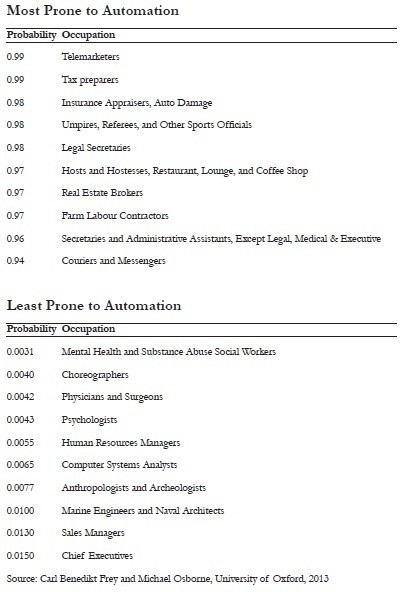

Perhaps the most discussed driver of inequality is the potential for the Fourth Industrial Revolution to increase unemployment. All industrial revolutions create and destroy jobs, but unfortunately there is evidence that new industries are creating relatively fewer positions than in the past. According to calculations by Carl Benedict Frey from the Oxford Martin Programme on Technology and Employment, only 0.5% of the US workforce is employed today in industries that did not exist at the turn of the 21st century, a far lower percentage than the approximately 8.2% of new jobs created in new industries during the 1980s and the 4.4% of new jobs created during the 1990s.

Furthermore, the type of jobs being created in these industries tend to require higher levels of education and specialized study, while those being destroyed involve physical or routine tasks. The Forum’s Future of Jobs Report surveyed leading human resources executives and presents evidence that future jobs will increasingly require complex problem-solving, social and systems skills. An upward bias to skill requirements disproportionally affect older and lower-income cohorts and those working in industries most prone to automation by new technologies.

Source: The Future of Jobs Report

Shifts in employment and skills may also increase gender inequality. Unemployment due to automation has in the past concentrated in sectors that mostly employ men, such as manufacturing and construction. But the ability to use artificial intelligence and other technologies to automate tasks in service industries puts many more job categories at risk in the future. These include jobs that are the source of livelihood for many young female workers and lower-middle-class women around the world, including call centre, retail and administrative roles.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution may affect inequality across economies as well as within them. In particular, the increasing flexibility of capital in the form of robots and other advanced manufacturing systems may erode the comparative advantage currently enjoyed by many emerging and developing countries, which are focused on labour-intensive goods and services. The phenomenon of “re-shoring” could have a particularly negative effect on those least developed economies just beginning to industrialize as they integrate into the global economy.

2. Security

Increasing inequality doesn’t just affect productivity, mental health and trust – it also creates security concerns for both citizens and states. The Forum’s Global Risks Report 2016 highlights that a hyper-connected world, when combined with rising inequality, could lead to fragmentation, segregation and social unrest. This mix of factors creates the conditions for violent extremism and other security threats enabled by power shifting to non-state actors.

Furthermore, the strategic space for conflict is changing. The combination of the digital world with emerging technologies is creating new “battlespaces”, expanding access to lethal technologies and making it harder to govern and negotiate among states to ensure peace.

The rapid spread of digital infrastructure thanks to the Third Industrial Revolution means that during the Fourth Industrial Revolution, cyberspace is now as strategic a theatre of engagement as land, sea and air. As Schwab puts it, “while any future conflict between reasonably advanced actors may or may not play out in the physical world, it will most likely include a cyber-dimension simply because no modern opponent would resist the temptation to disrupt, confuse or destroy their enemy’s sensors, communications and decision-making capability.”

The technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution also offer expanded capabilities for waging war which are increasingly accessible to both state and non-state actors, such as drones, autonomous weapons, nanomaterials, biological and biochemical weapons, wearable devices and distributed energy sources.

On the frontier of emerging military technologies are those that interact directly with the human brain to augment or even control soldiers. Even these are not limited to government military programmes. “It’s not a question of if non-state actors will use some form of neuroscientific techniques or technologies, but when, and which ones they’ll use,” argues James Giordano, from Georgetown University Medical Center. “The brain is the next battlespace.”

Such security fears are further augmented by the fact that a proliferation of dual-use technologies available to a wider range of actors makes it much harder to put into place international agreements and norms to support the peaceful resolution of conflicts. The security challenge of the Fourth Industrial Revolution will be one of coordinating large numbers of potentially lethal private and public sector actors in multiple strategic and cultural contexts. A difficult task indeed.

3. Identity, voice and community

In addition to concerns around rising inequality and threatened security, the Fourth Industrial Revolution will also affect us as individuals and members of communities. Already, digital media is increasingly becoming the primary driver of our individual and collective framing of society and community, connecting people to individuals and groups in new ways, fostering friendships and creating new interest groups. Furthermore, such connections transcend many traditional boundaries of interaction.

Unfortunately, expanded connectivity does not necessarily lead to expanded or more diverse worldviews. Paradoxically, the dynamics of social media use can serve to narrow available news sources. In addition, controversial or anti-establishment views can be further undermined by states and other actors willing to use new technologies and platforms to restrict speech and harass citizens, as detailed in the Forum’s Global Risks Report 2016. It is important that the emerging technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution increase diversity and the potential for collaboration rather than driving polarisation.

Emerging technologies, particularly in the biological realm, are also raising new questions about what it means to be human. The Fourth Industrial Revolution is the first where the tools of technology can become literally embedded within us and even purposefully change who we are at the level of our genetic makeup. It is completely conceivable that forms of radical human improvement will be available within a generation, innovations that risk creating entirely new forms of inequality and class conflict.

Conclusion

Martin Nowak, a professor of mathematics and biology at Harvard University, stated that cooperation is “the only thing that will redeem mankind”. If we have the courage to take collective responsibility for the changes underway, and the ability to work together to raise awareness and shape new narratives, we can embark on restructuring our economic, social and political systems to take full advantage of emerging technologies.

The complexity of the technologies driving the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the breadth of their impact means that all stakeholder groups to work together on innovative governance approaches. As Andrew Maynard from the Risk Innovation Lab points out, we should learn from, implement and extend thoughtful approaches to dealing with the intersection of technology and society such as anticipatory governance and responsible innovation, supporting widespread reflection on the development, commercialisation and diffusion of current and emerging technologies.

The goal of this reflection is naturally to ensure that emerging technologies and the Fourth Industrial Revolution improve lives in as broad-based and meaningful a way possible. However, even greater possibilities could emerge from bringing stakeholders together in new ways to discuss the future of technology and society.

As Schwab writes: “The new technology age, if shaped in a responsive and responsible way, could catalyse a new cultural renaissance that will enable us to feel part of something much larger than ourselves – a true global civilization… We can use the Fourth Industrial Revolution to lift humanity into a new collective and moral consciousness based on a shared sense of destiny.”

More on the Fourth Industrial Revolution

The 7 technologies changing your world

The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means

Health and the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.