War costs us $13.6 trillion. So why do we spend so little on peace?

A child holds bullets picked from the ground, in Rounyn, a village in North Darfur Image: REUTERS/Albert Gonzalez Farran

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Humanitarian Action

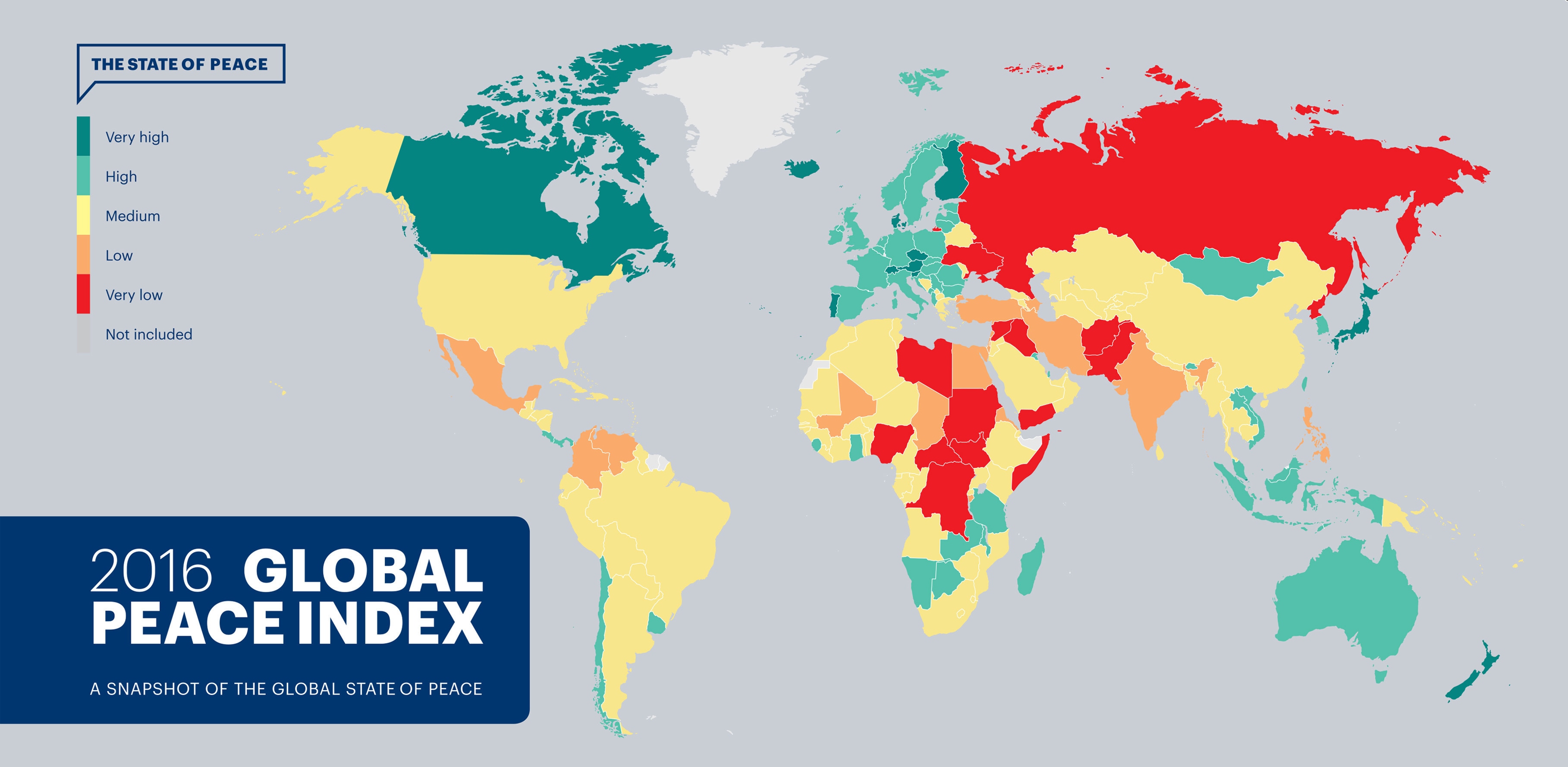

The latest Global Peace Index report, released today, finds that 2015 was a bad year for international peace and security. It recorded a further deterioration in global peace based on historic trends. 2015 witnessed the highest number of global battle deaths for 25 years, persistently high levels of terrorism, and the highest number of refugees and displaced people since World War II.

This violence had a huge cost. The report finds that the economic impact of violence to the global economy was $13.6 trillion in 2015 in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP). This is equivalent to $5 per day for every person on the planet, or 11 times the size of global foreign direct investment (FDI).

The toll of violence is typically counted in terms of its human and emotional cost, but the financial damage to the economy is yet another additional factor to consider. When counting the economic impact one must look at the costs of preventing and containing violence, as well as measuring its consequences. This is important because spending on containing violence, while perhaps necessary, is fundamentally economically unproductive.

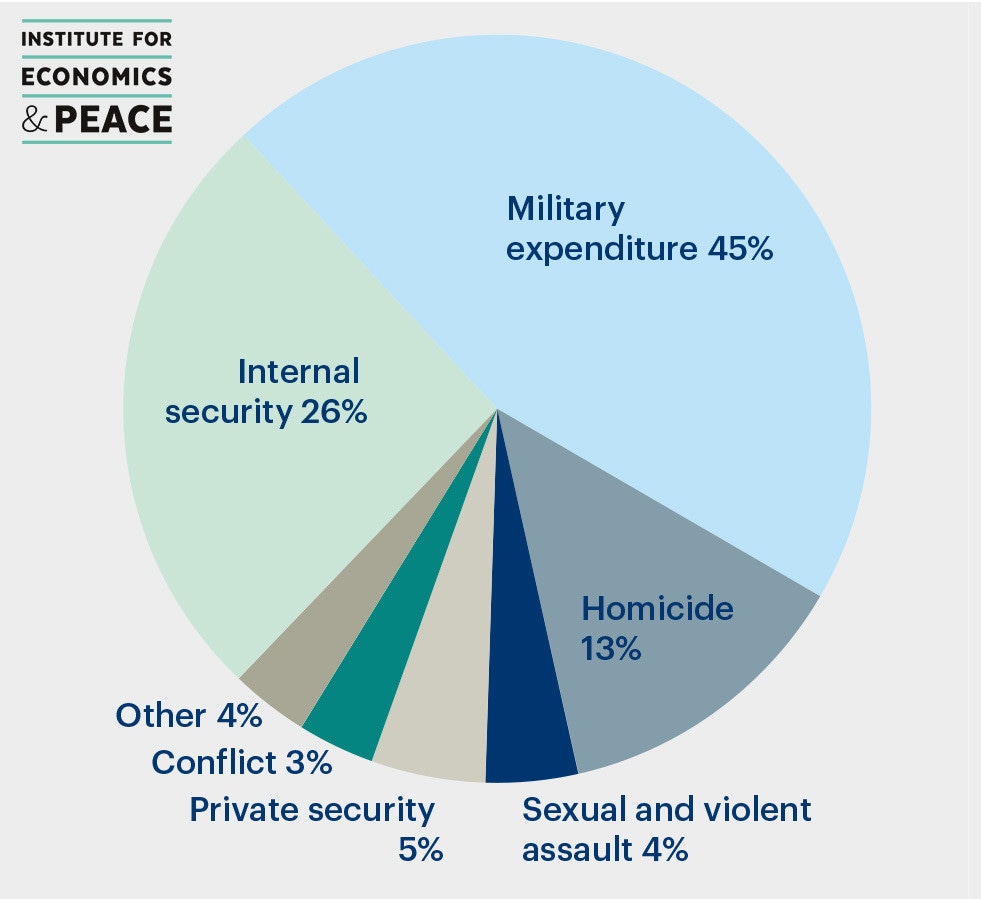

IEP’s method is a comprehensive accounting exercise to "add up" those direct and indirect expenditures related to creating and containing violence plus its consequential costs. These include not just military spending but domestic expenditures on security and police plus the losses from armed conflict, homicides, violent crime and sexual assault.

The $13.6 trillion of expenditures and losses represent 13.3% of world GDP. To break this figure down, it’s the equivalent of $1,876 for every person on the planet. The numbers refer to the current expenditures and their estimated flow-on effects in 2015, and are represented in PPP international dollars.

These numbers are notable for two reasons. Firstly, over 70% of the economic impact of violence accrues from what is mostly government spending on the military and internal security. This shows that significant amounts of government expenditure are tied up to this end. In a perfectly peaceful world, these huge resources could be directed elsewhere.

Secondly, the remaining amount is consequential losses from violence and conflict and these, too, are enormous. They significantly outweigh the international community’s spending on building peace.

A quick examination of the numbers reveals that the world continues to spend vastly disproportionate resources on creating and containing violence compared to what it spends on peace. In 2015 alone, UN peacekeeping expenditures of $8.27 billion totalled only 1.1% of the estimated $742 billion of economic losses from armed conflict.

When looking at peace-building – the activities that aim to create peace in the long term – those totaled $6.8 billion or only 0.9% the economic losses from conflict. The chart below highlights that the spending on peace-building and peace-keeping is minuscule when compared to the economic losses caused by conflict, representing just 2% in 2015.

But fundamental to future improvements in peace is a greater investment in peace-building and peace-keeping. Peace-keeping operations are measures aimed at responding to a conflict, whereas peace-building expenditures are aimed at developing and maintaining the capacities for resilience to conflict.

Peace-building expenditure aims to reduce the risk of lapsing or relapsing into violent conflict by strengthening national capacities and institutions for conflict management and laying the foundations of sustainable peace and development.

These numbers suggest a serious under-investment in the activities that build peace and demonstrate that the international community is spending too much on conflict and too little on peace. Given the fact that the cost of violence is so significant, the economic argument for more spending on peace is indeed powerful.

Furthermore, a new phenomenon is emerging as some countries grow more peaceful while overall levels of violence increase: peace inequality. This drives a broader dynamic of greater economic inequalities between nations; as the least peaceful countries spiral into greater violence and conflict, they are also further set back economically.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Humanitarian ActionSee all

Lisa Satolli

April 18, 2024

Spencer Feingold

March 22, 2024

Weekend reads: Our digital selves, sand motors, global trade's choke points, and humanitarian relief

Gayle Markovitz

March 15, 2024

Kalkidan Lakew Yihun

March 11, 2024

Liam Coleman

March 7, 2024

Andrew Herscowitz

February 27, 2024