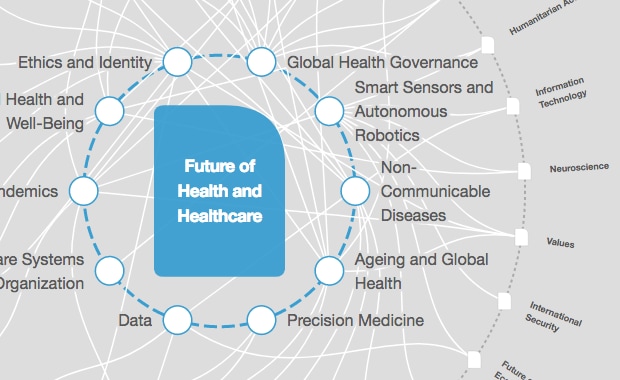

A new weapon in the fight against cancer: sticky nanoparticles

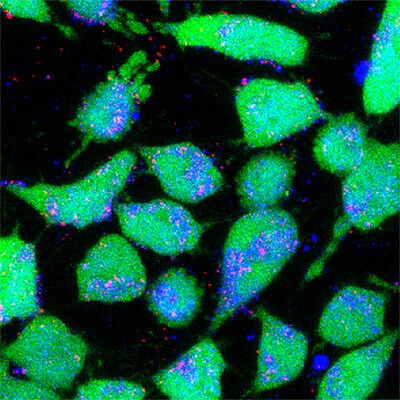

The nanoparticles are loaded with a drug known as epothilone B. Image: REUTERS/Jonathan Bachman

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Health and Healthcare

Sticky nanoparticles that deliver drugs precisely to their targets — and then stay there — could play a crucial role in fighting ovarian and uterine cancers.

A team of researchers at Yale found that a treatment using bioadhesive nanoparticles loaded with a potent chemotherapy drug proved more effective and less toxic than conventional treatments for gynecological cancer. The results of the work, led by professor Mark Saltzman at the Yale School of Engineering and Applied Science and professor Alessandro Santin at the Yale School of Medicine, appear Sept. 19 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The nanoparticles are loaded with a drug known as epothilone B (EB) and injected into the peritoneal space, the fluid of the abdominal cavity. EB has been used in clinical trials to target tumor cells resistant to conventional chemotherapy agents. The drug proved effective in these trials, but severe side effects caused by the drug’s high toxicity prevented further use.

The Yale Cancer Center researchers’ treatment significantly reduces the drug’s toxicity by encasing it in a nanoparticle that gradually releases the drug in high concentration at the cancer site. The problem with conventional nanoparticles, though, is that they are cleared from the target region too quickly to have much of an effect due to their small size, note the scientists.

“The challenge was to find a way to use that drug, which is very effective if you can keep it in the right place for a long enough period,” said Saltzman, the Goizueta Foundation Professor of Biomedical and Chemical Engineering.

To that end, the Yale team developed nanoparticles covered with aldehyde groups, which chemically adhered to mesothelial cells in the abdominal cavity when injected into the peritoneum. Tested on mice with human tumors growing in their abdominal regions, the bioadhesive nanoparticles stayed in place for at least 24 hours. Non-adhesive nanoparticles injected into control mice began to leave the abdominal cavity after five minutes. Sixty percent of the mice receiving the treatment with the bioadhesive nanoparticles survived for four months — a significant improvement over mice in the control groups, where 10% or fewer lived as long.

By localizing the delivery of the drug, Santin said, they both decreased the toxicity of the drug and increased its effectiveness. This treatment could be particularly beneficial to patients with later stages of ovarian and uterine cancer, which is extremely difficult to treat due to how the cancer spreads in the peritoneal region, he said.

“They’ve been treated with surgery and chemotherapy and are now resistant to any standard treatment, and we’ve shown that this agent can be effective,” said Santin, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences, and research team leader of the Gynecologic Oncology Program at Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven.

For future studies, Saltzman said, they may “tune” the nanoparticles’ properties. For instance, they can adjust the adhesiveness of the particles, and how quickly the particles release the drugs at the target site.

Additional co-authors of the paper, all from Yale, are Yang Deng, Fan Yang, Emiliano Cocco, Eric Song, Junwei Zhang, Jiajia Cui, Muneeb Mohideen, and Stefania Bellone.

The work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Women’s Health Research at Yale.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Health and HealthcareSee all

Johnny Wood

April 17, 2024

Adrian Gore

April 15, 2024

Carel du Marchie Sarvaas

April 11, 2024

Nancy Ip

April 10, 2024

Shyam Bishen

April 10, 2024