Artificial intelligence will save jobs, not destroy them. Here's how

Image: REUTERS/Thomas Peter

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

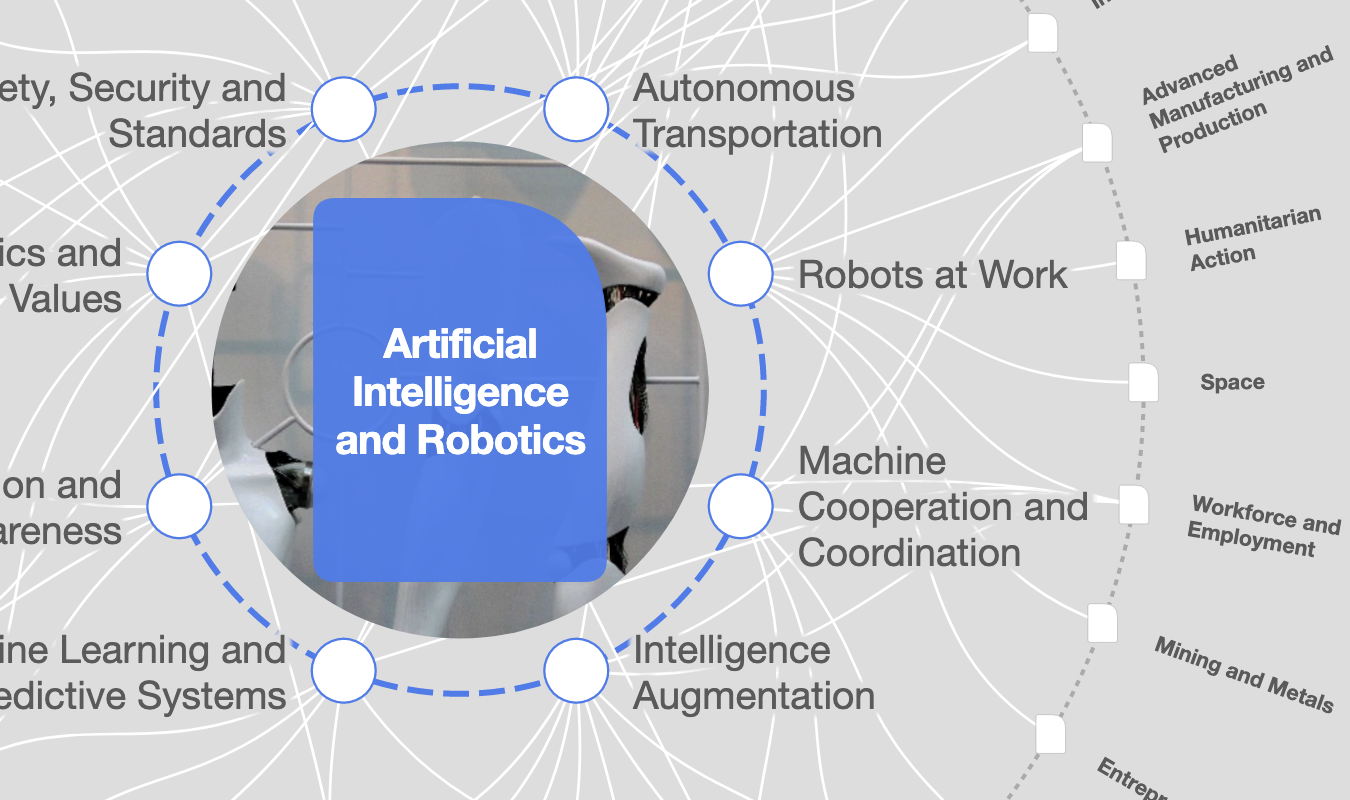

Artificial Intelligence

In the latter half of the 1980s a debate ensued between two camps of economists roughly grouped around the views of Edward Prescott, on the one hand, and Lawrence Summers, on the other.

Prescott argued that by and large, the booms and busts of the economic cycle were due to “technological shocks”; and Summers dismissed the notion as speculation not supported by evidence.

Over the years, the ‘technological shock’ model of economic shifts (TS) has surfaced over and over again in many forms, rising to the occasion whenever the debate over cycles rears its head.

Today, TS has penetrated the discussion on the nexus between Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the employment situation in advanced economies, with some AI enthusiasts like former Googler Sebastian Thrun offering fodder to those economists who are pessimistic about the impact of technology on the job market.

The famous Oxford Martin study by Frey and Osborne in 2013 concluded that “[a]ccording to our estimates, about 47 percent of total US employment is at risk.” It did offer the somewhat elite-reassuring view that the highest paid jobs and those requiring the highest educational attainment (and the two categories are often conjoined) might be safe for a significant time. The question, of course, is: “for how much longer?”

To be blunt, trying to predict the future more than two decades at a stretch is more science fiction than anything else. This article will thus focus on the ‘near horizon’ rather than the ‘distant future’.

A full generation after the Prescott-Summers debate, the issue of ‘productivity’ remains central. In recent comments, Summers has pointed to an interesting anomaly: despite the significant withdrawal of many blue collar jobs from the US economy (and others like it), partly because of the march of automation, productivity growth has been unimpressive, or even anemic.

There are hints in the data, both formal and anecdotal, if one cares to look carefully that while technology may be improving the quality of life on the whole, its aggregate effect on enterprise efficiency could be exaggerated, which is precisely the suspicion that led me to this subject and to this article.

The subconscious trigger, however, must have been comparing the efficient flow of Fortnum & Mason’s human-manned checkout-tills in London’s Bond Street, with the relative bumbling at Sainsbury’s robot-manned checkouts less than a mile away.

At the time I made my impressions I was not aware of a damning study at the University of Leicester in 2015 which had found that the robot-checkout contraptions could trigger everything from aggressive behaviour to increased shoplifting, and that they were actually losing the supermarkets significant amounts of money.

When they first launched, the pitch was that auto-checkouts would save shoppers 500,000 hours of unnecessary queuing time. The reality today is depressingly different.

Similar attempts by Australian mining giants to induce human redundancy using robots have been beset with glitches, have led to lost production, and hasty retreats from the technology.

It is not surprising then that a careful look at the actual flow of R&D dollars into AI in many of the most tech savvy companies reveals a less prominent role for ‘hard automation’, defined roughly as ‘machine induced human redundancy (MIHRED), than is usually perceived to be the case.

Salesforce’s recently launched product, Einstein, focuses on helping salespeople write superior emails to targeted prospects. SAP’s HANA is integrating AI to help users better detect fraudulent transactions. Enlitic promises algorithms to make junior doctors read x-rays faster and more accurately, not to replace them. Affectiva wants to use its deep-learning kit to help empathy-challenged people become more emotively competent. It goes on and on.

At play here are two interlocking principles: the ideas of ‘digital bicephaly (dibicephaly)’ - a literal new ‘exended-hemisphere’ of the brain where accurate measurement, a behaviour largely alien to the human mind, can thrive on demand – and ‘cognitive exoskeletons (COGNEX)’ – a concept related to Flynn’s thesis of ‘new cognitive tools’ driving incremental increases in observed human IQ.

This is no Engelbart and Kurzweil style ‘machine-human symbiosis’ utopia however.

At the root of the cognex-dibicephaly vision of the future is, rather, a strong emphasis on the workplace and on the ‘mid-range’ scale of capabilities in both humans and machines (pseudo-AI). There are two contexts that converge on the same point.

Firstly, most people think of automation through the lens of assembly-line logic. Actually, ‘automation’ is a softer and more pervasive feature of all modern management. Every modern company in the world has been deploying more and more supply chain management (SCM), customer response management (CRM) and enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems in a bid to automate more and more functions. Rather than Human redundancy, improved HUMAN productivity has been the chief driver.

The problem though is that, as Denver-based Panorama Consulting has noticed, only 12% of companies report full satisfaction with their automation programs.

Gartner has found that 75% of all ERP implementations fail. In fact, Thomas Wailgum (a top executive of the American SAP Users Group) once estimated that the chances of a successful ERP implementation may be closer to 7%.

Poor automation outcomes make experimenting with innovative business models harder and prone to failure, and the single most cited cause is poor “personnel interfacing”. In every major lawsuit in the wake of a failed implementation, like Bridgestone’s $600 million suit against IBM, personnel-automation incongruity rise to the top of the pile. It has been widely observed that attempts to circumvent rather than enhance human input typically constitute the key failure points.

The question, it would seem then, is not how to remove humans from the chain altogether, but how to embed them more seamlessly.

The second point is the issue of ‘unfilled jobs’.

America alone has nearly 5.8 million of them. George Washington University’s Tara Sinclair is the lead author of a recent report that showed that a quarter of advertised jobs in the US and about a fifth in other rich countries like Canada and Germany were going unfilled.

The report correctly tied this mismatch of human skills and labour requirements with the sluggish growth in global productivity and thereby casts a more interesting complexion on the issue of human redundancy and artificial intelligence, at least in the near-term horizon.

In the same way that personnel inadequacies continue to undermine efforts to automate the enterprise, skills imbalances inflate unemployment rates and exaggerate the effect of efficiency-inducing technology. And both dynamics are strongest not in the unskilled or the superskilled segments (the tail-ends) but in the ‘middle-bulge’ of the employment curve.

It is reasonable to infer, given this background, that large-scale human redundancies caused by transhuman AI are fanciful, at least in the near-term horizon, given the actual performance of automation and the gaps in the enterprise today.

What is more likely is the proliferation of mid-tier AI systems transforming the capacity of mid-level skilled workers to better fill vacant jobs and to participate in human-critical automation of the enterprise, and in the search for novel business methods and models.

With superior virtual reality and machine-iteration systems, average food technologists can carry out a more varied range of biochemical explorations. Nurses can perform a wider range of imaging tests. Fashion design trainees can contribute more effectively to the fabric technology sourcing process.

And so on and so forth.

With improving personnel agility comes more nimble business models and an expansion of the job market.

Add these prospects to the potential productivity lift and the better synching of job openings and personnel availability and a whole new vision of what pro-human or cis-human AI might do for the job market emerges, one that is starkly different from the dystopian prophecies tethered to the rise of trans-human AI.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Artificial IntelligenceSee all

TeachAI Steering Committee

April 16, 2024

Darko Matovski

April 11, 2024

Juliana Guaqueta Ospina

April 11, 2024

Allan Millington

April 10, 2024