One. That's how many careers automation has eliminated in the last 60 years

Though almost all of today’s jobs have some aspect that can be automated by current technology, very few jobs can be entirely automated. Image: REUTERS/Dave Kaup

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

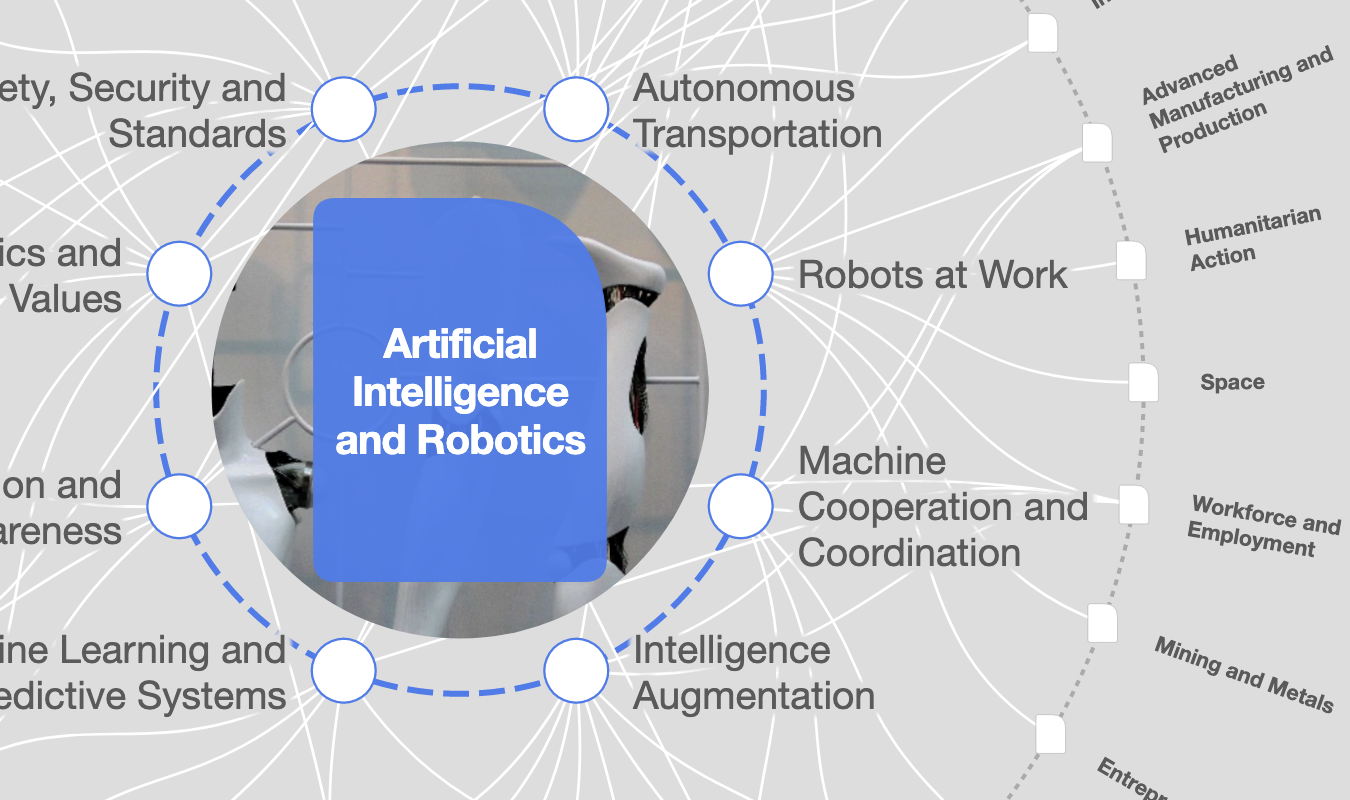

Artificial Intelligence

Automation often replaces human labor, but very rarely in the last sixty years has it eliminated an entire occupation.

Only one of the 270 detailed occupations listed in the 1950 US Census has since been eliminated by automation, according to a working paper by Harvard economist James Bessen. The one exception: elevator operator.

While the government has removed other occupations from the Census due to factors like lack of demand (boardinghouse keepers) and technological obsolescence (telegraph operators), only elevator operators owe their occupation’s demise mostly to automation, Bessen found.

The pattern of the last 60 years is likely to continue. Though almost all of today’s jobs have some aspect that can be automated by current technology, very few jobs can be entirely automated, according to a recent McKinsey analysis.

“This distinction is important because it implies very different economic outcomes,” Bessen wrote in a column last year. “If a job is completely automated, then automation necessarily reduces employment. But if a job is only partially automated, employment might actually increase.” This is what happened when weaving technology advanced during the Industrial Revolution, for instance. The price of cloth dropped, more people bought cloth, and factories hired more people to keep up with demand—even though each worker could, with the help of machines, be much more productive.

That is the positive scenario. For some products and services, falling prices won’t create more jobs, because falling prices won’t increase demand. And then there’s always the argument that modern technology is advancing so quickly that nothing about how the economy has adapted to new technologies in the past is relevant.

In any case, in the story of automation and jobs, elevator operators really got shafted.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Artificial IntelligenceSee all

TeachAI Steering Committee

April 16, 2024

Darko Matovski

April 11, 2024

Juliana Guaqueta Ospina

April 11, 2024

Allan Millington

April 10, 2024