6 charts on education around the world

The OECD report card is in. How does your country compare? Image: REUTERS/Eric Gaillard

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Education

The world is more educated than ever before, with the average number of years spent in school increasing constantly. So how do levels of education in your country compare?

A new report from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Education at a Glance 2017, looks at the state of education in all 35 member countries and a number of partner countries.

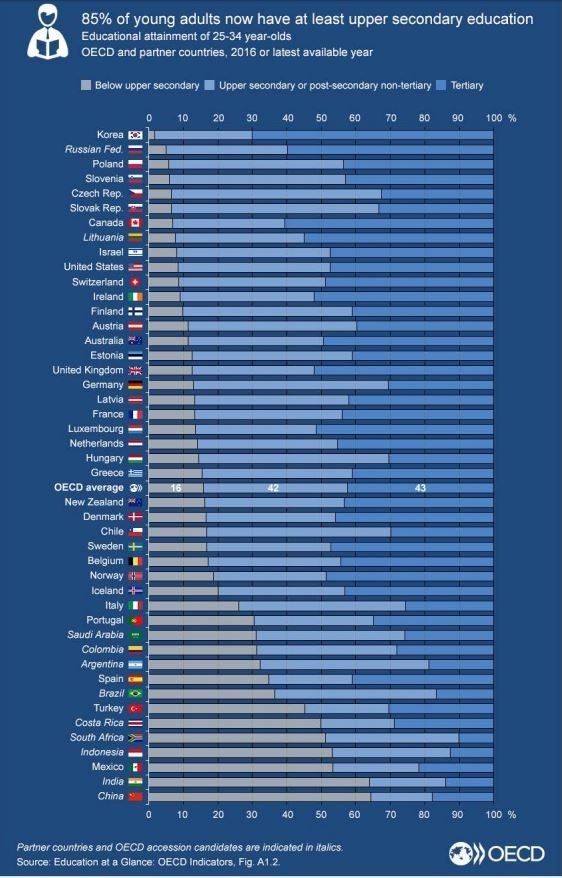

It found that 85% of young adults (aged 25 to 34) have attained upper secondary education, which typically starts at around 15 or 16 years old.

Almost half (43%) have gone further and have a tertiary degree. In some countries the proportion of young adults with a university degree is even higher, at 50% or more including Canada (61%), Ireland (52%), Japan (60%), Korea (70%), Lithuania (55%) and the Russian Federation (60%).

Primary and secondary education

On average across OECD countries, only 6% of adults have not gone further than primary school.

In some countries, however, this percentage is much higher. A quarter of young adults in China (25%) and Saudi Arabia (24%) never made it past primary school. This figure rises to around one-third or more in Costa Rica (29%), Indonesia (43%), Portugal (30%), and Turkey (43%).

The share of young adults who have not reached upper secondary education is 16% on average across OECD countries.

But it’s much higher than that in some countries: more than half of young adults lack an upper secondary or higher education in China (64%), Costa Rica (51%), India (64%), Indonesia (53%), Mexico (53%) and South Africa (51%).

Parental education really matters

The most important factor when it comes to predicting a child’s future education level is parental education.

A young person is much more likely to study for a degree if one or both of their parents have.

The only exception is Japan, where gender and parents’ educational attainment seem to have an equal influence.

What do they study?

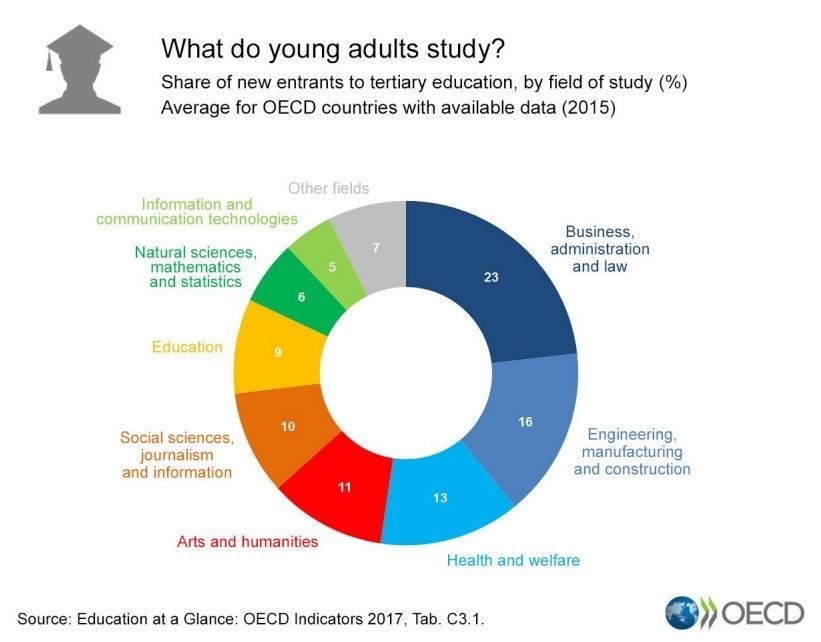

Business, administration and law are by far the most popular areas of study in the countries surveyed, chosen by around one in four students (23%).

This varies across countries, of course. In Korea it’s only 14%, while in Luxembourg it’s 37%.

Yet in terms of employability, young people would be better off studying science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects, according to the report.

Only 16% study engineering, construction and manufacturing, and less than 5% of students opt for information and communication technologies (ICT), despite graduates in these subjects having the highest employment rate on average across OECD countries.

The gender imbalance

Women’s participation in higher education has been increasing across the countries surveyed in recent years. Women are also more likely to complete their degrees than men.

Yet they will earn less.

Average earnings are higher for degree-educated men than for their female peers. Also, rates of employment for men with tertiary degrees tend to be higher than for women with the same level of education.

There is an obvious gender gap in the subjects that young adults choose at university. Far more women than men choose to study education and health and welfare.

And many more men than women study STEM subjects and ICT. Close to three out of four engineering students and four out of five ICT students are men.

That’s despite the fact that on average, girls outperform boys in the PISA science test.

Results from the PISA 2015 assessment indicate that boys’ and girls’ career paths start to diverge well before they actually select a career.

Boys are more likely than girls to envisage themselves in a science-related career when they are 30. Meanwhile, more than seven out of 10 teachers on average across OECD countries are women. Given the number of women choosing to study education versus men, this is unlikely to change soon. Teachers earn up to 60% less on average than similarly educated workers.

Graduate premium

There is also a gender imbalance for the graduate premium – the extra money a graduate can expect to earn as a result of the extra study.

There are only two countries where women see a higher net return from university study than men: Spain and Estonia. For the average woman elsewhere, net financial returns for tertiary education are $167,400, representing only two-thirds of those for a man.

In seven countries, men saw a higher return of up to 50%. The difference was particularly pronounced in Japan, where male graduates can expect a net financial return of almost $240,000, compared with just $28,200 for women.

Spending on education

As a percentage of GDP, the UK spends more on education than any other OECD country, followed closely by Denmark and New Zealand.

France and Sweden spend the least as a percentage of their GDP.

Benefits of higher education

The benefits of a university education remain high. University graduates are more likely to be employed, they earn 56% more than those without a degree, and they are less likely to suffer from depression.

“Tertiary education promises huge rewards for individuals, but education systems need to do a better job of explaining to young people what studies offer the greatest opportunities for life,” said OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría.

“Equitable and high-quality education fuels personal fulfilment as well as economic growth. Countries must step up their efforts to ensure that education meets the needs of today’s children and informs their aspirations for the future.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on EducationSee all

Natalia Kucirkova

April 17, 2024

Morgan Camp

April 9, 2024

Scott Doughman

March 12, 2024

Genesis Elhussein and Julia Hakspiel

March 1, 2024

Jane Mann

February 28, 2024

Malvika Bhagwat

February 26, 2024