Here's how Finland solved its homelessness problem

Finland found a simple solution to its homelessness problem: giving people a place to stay. Image: REUTERS/John Schults

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Inequality

In the last year in the UK, the number of people sleeping rough rose by 7%. In Germany, the last two years saw a 35% increase in the number of homeless while in France, there has been an increase of 50% in the last 11 years.

These are Europe’s three biggest economies, and yet they haven’t solved their housing problem. Across Europe, the picture is much the same.

Except in Finland.

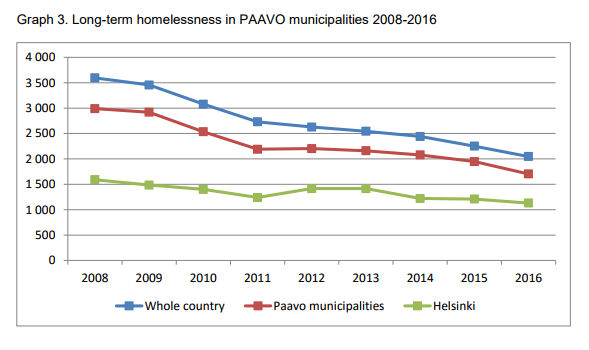

There, the number of homeless is steadily decreasing. So what have they been doing differently?

An ideology

The Finns have turned the traditional approach to homelessness on its head.

There can be a number of reasons as to why someone ends up homeless, including sudden job loss or family breakdown, severe substance abuse or mental health problems. But most homelessness policies work on the premise that the homeless person has to sort those problems out first before they can get permanent accommodation.

Finland does the opposite - it gives them a home first.

The scheme, introduced in 2007, is called Housing First. It is built on the principle that having a permanent home can make solving health and social problems much easier.

The homeless are given permanent housing on a normal lease. That can range from a self-contained apartment to a housing block with round-the-clock support. Tenants pay rent and are entitled to receive housing benefits. Depending on their income, they may contribute to the cost of the support services they receive. The rest is covered by local government.

Since the scheme started, thousands have benefitted.

Constant support

At the same time as being given a home, they receive individually tailored support services.

For instance, anyone can reserve an appointment with a housing advisor and receive advice in things like problems with paying the rent or applying for other government benefits.

There are also financial and debt counselling services to help people manage their finances and debts.

Much of the support can be provided in their own home.

Housing First works so well because it is a mainstream national homelessness policy with a common framework, according to Juha Kaakinen, Chief executive of Y-Foundation, a social enterprise that provides housing to Housing First. It involves a wide partnership of people: the state, volunteers, municipalities and NGOs.

More affordable housing

Chronic housing shortages contribute to homelessness. In Finland, increasing the supply of affordable rental housing was a critical part of the approach.

Finland used its existing social housing, but also bought flats from the private market and built new housing blocks in order to provide homes.

There are no more homeless shelters in Finland. They have all been turned into supported housing.

It all costs money, but it saves more

“All this costs money,” admits Kaakinen. “But there is ample evidence from many countries that shows it is always more cost-effective to aim to end homelessness instead of simply trying to manage it. Investment in ending homelessness always pays back, to say nothing of the human and ethical reasons.”

The savings in terms of the services needed by one person can be up to 9,600 euros a year when compared to the costs that would result from that person being homeless, he adds.

No consensus

Not everyone in Finland was happy with the new policy.

Firstly, many of those working with the homeless objected to the idea that they should receive a home first, without having to sort out any of their problems first.

But Housing First argues that it’s much more difficult to solve any problems without having a roof over your head. In the words of one person who benefitted from the scheme: “Homelessness also meant daily alcohol use. It was not so much about getting drunk, but a way to pass the time. When I’ve had an apartment, I’ve spent several months without drinking. You can’t get sober when you’re homeless, no one can.”

And in residential areas where new housing blocks were established, many residents were unhappy. They were worried that it would adversely affect their neighbourhood.

Part of the approach of Housing First is that a sense of community is very important. For instance, when a new housing block is built, much work is done in the local neighbourhood at the same time.

That includes keeping the local community informed through open house events, encouraging residents to interact openly with the local community as well as working in the local community picking up litter and taking care of the neighbourhood’s green spaces.

When a new supported housing unit opens, it typically takes about two years for the area to get accustomed to the unit and its residents. It takes about the same amount of time for the unit’s residents to adjust well to the environment.

Another issue with the policy was that it didn’t seem to be reaching women. Women’s homelessness has not decreased, even though homelessness and long-term homelessness in general has. Consequently, closer attention has been paid to solving and finding solutions to women’s homelessness.

Can this work abroad?

The Y-Foundation believes that the model can be replicated in Europe, even though housing conditions vary.

In the UK, a study by the homeless charity Crisis found that a policy of this kind in the UK could be more than five times as effective and nearly five times more cost-effective than existing services.

But a recent Government report concluded that, whilst the work of Housing First in Finland was to be commended, “we believe that resources should be focussed on supporting more mainstream efforts to tackle homelessness and prevent instances of entrenched homelessness.”

Kaakinen says: “There is no quick fix to all life situations but a solid base provides the foundations upon which to improve the welfare of the homeless. The first step in change is the change in attitudes.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on InequalitySee all

Liam Coleman

March 7, 2024

Nicolai Ruge and Danny Quah

February 28, 2024

Sreevas Sahasranamam

February 20, 2024

Charlotte Edmond

February 8, 2024

Samantha Akwei and Ginelle Greene-Dewasmes

February 5, 2024

Andrea Willige

February 5, 2024