We've lost 60% of wildlife in less than 50 years

Many of us find it hard to grasp the real pace of decline going on in the natural world. Image: REUTERS/Baz Ratner

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

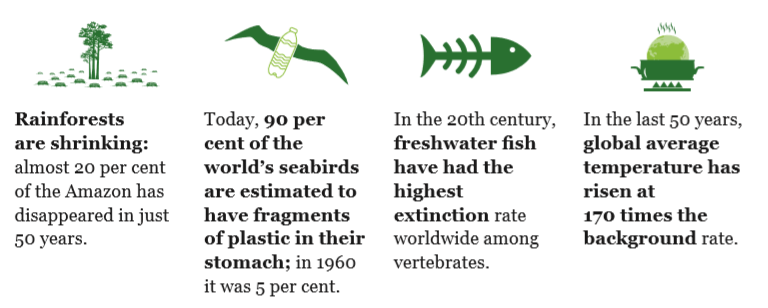

Human activity is having a devastating impact on our planet. But while most people understand how pollution, resource depletion and loss of biodiversity are pushing the natural resources to the brink, the reality can seem distant and difficult to quantify. Many of us find it hard to grasp the real pace of decline happening in the natural world. Sir David Attenborough has witnessed it first hand, and calls humans a plague on earth -- encapsulating in just a few words the widespread destruction we are responsible for.

The WWF’s latest Living Planet Index reveals just how rapid and dramatic those shifts are, calculating that the population abundance of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish has decreased by more than half in less than 50 years. The report attributes the declines to habitat loss, pollution, climate change, over-exploitation and the spread of invasive species and diseases, underscoring environmentalists’ concerns that human activity is taking a heavy toll.

This “is a grim reminder and perhaps the ultimate indicator of the pressure we exert on the planet,” said Marco Lambertini, the director general of WWF International. “There cannot be a healthy, happy and prosperous future for people on a planet with a destabilized climate, depleted oceans and rivers, degraded land and empty forests.”

If that seems bleak, the detailed findings and lack of commonly agreed solutions make it bleaker still, with current targets and actions amounting “at best, to a managed decline,” according to the report.

Lambertini said humans are facing “an unparalleled, yet rapidly closing, opportunity” to rethink how they value nature, and called for a “new global deal.”

The statistics are arresting. From 1970 to 2014 vertebrate population sizes plummeted by 60%, while freshwater populations sank by 83%.

An example of a critically endangered species is the gharial, found in India and Nepal.

Three other gauges in the report give context, all pointing to continued loss of biodiversity. The Species Habitat Index measures the suitable habitat available for each species, the IUCN Red List Index tracks extinction risk, and the Biodiversity Intactness Index, monitors how much of a region’s original biodiversity remains. Species’ population declines were the most dramatic in South and Central America, dropping 89% compared to 1970.

If that’s not enough, four so-called planetary boundaries have already been pushed beyond safe limits: climate change, biosphere integrity, biogeochemical flows (nitrogen and phosphorus) and land-system change.

The report authors suggest three steps for improvement and called on decision-makers at every level to take action. Setting clearly defined goals, developing a set of measurable and relevant indicators of progress, and agreeing actions as well as a time frame would help alleviate the current pressures, they wrote.

Such a framework should be drawn under the Convention on Biological Diversity, as it’s an international legal instrument. The UN Biodiversity Conference is due to be held in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, in November.

“It’s clear that efforts to stem the loss of biodiversity have not worked and business as usual will amount to, at best, a continued, managed decline,” the report said. “That’s why we, along with conservation and science colleagues around the world, are calling for the most ambitious international agreement yet – a new global deal for nature and people – to bend the curve of biodiversity loss.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Future of the EnvironmentSee all

William Austin

April 17, 2024

Victoria Masterson

April 17, 2024

Rebecca Geldard

April 17, 2024

Johnny Wood

April 15, 2024

Johnny Wood

April 15, 2024