Beth Comstock's Imagine It Forward: An excerpt

Have you joined our book club? Image: REUTERS/Albert Gea

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Book Club

This excerpt is from Beth Comstock's book "Imagine It Forward". The book was chosen as April's book for the World Economic Forum Book Club. Each month, a new book will be selected and discussed in the group. The author will then join in on the last day of the month to reply to some questions from our audience.

Join here: wef.ch/bookclub

I was able to see the sunset fade from red to purple as the plane began to descend over the rolling hills of Northern Virginia. A few moments later we were down, puttering to a stop in a small airstrip carved into rural Virginia farmland barely 40 miles from where I’d grown up. A man in a blue jumpsuit waved me over after the pilot had helped me down the plane’s narrow stairs to the grass. As I walked toward him, carrying my overstuffed tote bag, notes hastily crammed in the side pocket, I heard the plane’s engine fire back up. Soon it was rid-ing up over the trees, and banking into the purple sky. “Anything I need to know?” I asked. “Sorry, ma’am. They just pay me to bring the planes in and then guide them back out,” he said.

I didn’t know exactly who was going to pick me up, and I had no number to call. All I knew was that the CIA wanted my advice. I closed my eyes and inhaled the autumn air. Wild grasses, oak and pine trees. The smell of home. Soon a black SUV with tinted windows pulled up in front of me. Three men get out, each in a dark jacket and, of course, aviator- style glasses. “Beth? Come with us.” We talked a bit about the weather, about my hometown (where one of them lived), before I turned my mind to the notes I’d scrib-bled down after a brief talk with the CIA deputy director a few days before: We’re siloed. We need to collaborate more with each other and across the agency. It’s hard to keep up with the pace of change. We’re in the busi-ness of secrets and yet we need to continually open up to new per-spectives, to taking risks, and being ready when change shows up. We need to continually reinvent ourselves. Although it would be my first time lecturing our nation’s spy-masters, the worries they expressed were the same urgent concerns I have been hearing from organizations and businesses around the world: How do we navigate the relentless pace of change? How can we open up our culture and innovate more quickly? How do we stay relevant in a world that is being constantly disrupted? Inside a CIA training center, about thirty- five regional leaders were having predinner cocktails. I’ve been brought into this kind of gathering on hundreds of occasions. Sometimes I play the spark, an instigator to seed new ideas and directions for change. Sometimes I’m brought in to play the explorer, teaching others the process I use to truffle- hunt for new ideas. Other times I’m the champion, preaching the need for leaders to support the lonely voices at the edge that are calling on their organizations to change.

And sometimes my role is to coach a team to create the prototypes that will serve as the “proof points” that justify a leap into the new. As we chatted, they didn’t talk about what they did, which I understood, of course. But I found it telling how eager they were to steer the conversation away from the work I did— spreading change. It’s not polite dinner conversation. It’s easier to keep your nose to the grindstone, do what you are doing and do it well, than it is to lift your head up and figure out where you or your organization is going and what the future may bring. It’s usually not until an organization is engulfed by chaos or, more simply, wakes up to a stark reality that it has been left behind, that it begins to seek a new way forward. And by that point it lacks either the energy or the time to make it through to the other side. Fifty years ago, the life expectancy of a Fortune 500 firm was around seventy- five years; now it’s less than fifteen. And the sobering reality is that the world is never going to be slower in terms of change than it is today. Futurist Ray Kurzweil predicts that “we won’t experience 100 years of progress in the 21st century— it will be more like 20,000 years of progress.” What we are witnessing is the battle for the future of many of our businesses. One of the defining characteristics of our new age of rapid- fire change is that leaders, managers, and employees have to be able to move forward without having all the answers. They have to feel their way in the dark. It is very disconcerting, particularly when you have to do it at full speed. They know they need to be more inventive to succeed, but they admit to being uncomfortable with creative people and their rule- breaking ways. They realize they need to partner more with other companies, but are afraid of reaching beyond their own insular communities. They know they need to make changes, but want proof of success before doing so. I’ve been courting change my whole career. It has taken me from media manager to Business Innovations leader and vice chair for GE, a company that lived through 125 years of change and adaption.

I’m known as a change wrangler, the person who chases tornados of disruption, driving full speed into the funnel clouds. Not a week goes by when I don’t hear from some leader or practitioner seeking advice on how to reinvent their way forward. An Australian official asks me to be part of a working group to outline a vision for Australia 2030; they want to know how to “surf the crest of the wave of change.” A team manager asks me how to convince her boss to pursue a big idea— the customer needs it desperately. An executive at a major broadcast network calls me to brainstorm how to help her people spot disrupters before the competition does. An energy executive corners me after the Saudis initiated a major OPEC price cut and caused a collapse in oil prices. “How the hell did I miss that?” he wondered. I’ve learned that you have to pay close attention to what’s emerging before it turns into a crisis or an emergency for your company or industry. Things are good until they aren’t. The question about how to respond to the uncertainty and the chaos is coming from many quarters now: the taxi industry, the media world, big box and one- store retail, the post office, the school board. “How do I get a handle on change? How do we adapt, evolve, thrive?”

As the CIA dinner came to dessert, I walked to a lectern at the front of the room. I smiled at their skeptical expressions and said hello. I was about to tell them the message of this book in front of you. But first I was going to have to answer two questions that you probably have as well: Why are so many of our organizations shortsighted— unable to see around corners and unable to move forward in the face of accelerating change? And, why do people think I have some of the answers that will lead them to the way forward? About three years after the September 11 attacks, an independent commission issued a report that cited “deep institutional failings” at the CIA leading up to the attacks. The most important failure, it said, was “one of imagination.” What started out as seemingly isolated, episodic incidents has come to resemble an epidemic. We are failing in government, fail-ing in education, and, too often, failing in business. Thrust into an unpredictable and profoundly complex world, the nature of today’s challenges cannot be solved by yesteryear’s tried- and true expertise. Instead of investing more resources in understanding the art and science of innovating our way forward, we’ve doubled down on the diminishing returns of financial engineering. That is why we are now confronting such a huge gap between the knowledge, critical thinking, problem- solving, and creativity needed to survive the challenges and exploit new opportunities, and our dogged insistence on doing things as they’ve always been done. I call this the imagination gap, where possibility and options for the future go to die. But I refuse to give up on possibility. We have to narrow the gap— that is why I had to write this book.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Book ClubSee all

Ian Shine

November 27, 2023

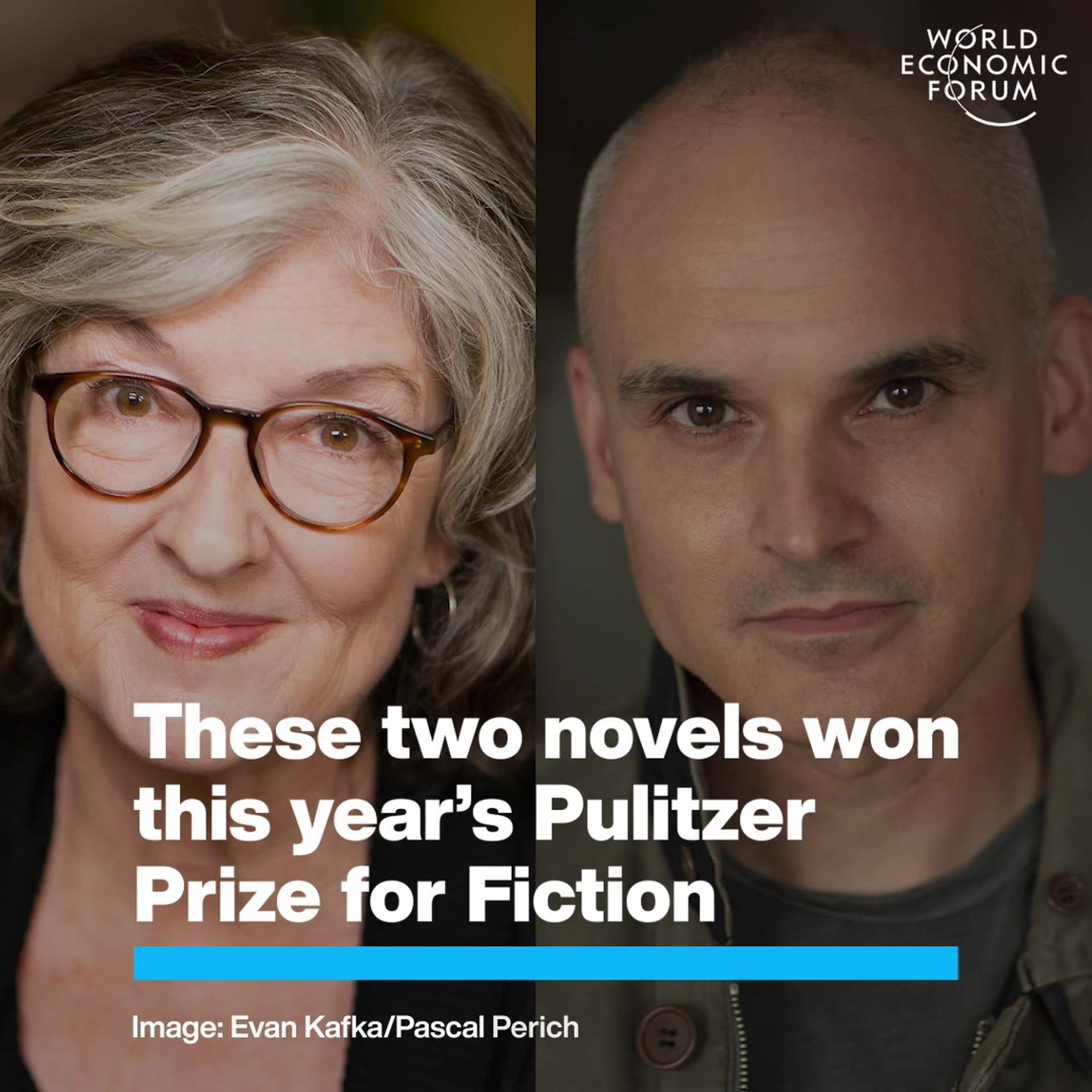

Rebecca Geldard

June 2, 2023

Emma Charlton

May 31, 2023