We need to predict human-machine errors before they happen – here's how

Today, industrial policy is back on the agenda. Image: REUTERS/Remo Casilli

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Emerging Technologies

In the January 1954 issue of The Atlantic, John F. Kennedy, then the junior US senator from Massachusetts, argued that the ongoing migration of industries from New England to the American South should not be hindered. He called on the government instead to provide loans and other forms of support to assist New England-based businesses, retrain industrial workers, and fund local industrial development agencies.

Kennedy recognized that the government had an important role to play in both lifting the South and spurring new industries in New England. Today, industrial policy is back on the agenda, after having spent decades on the fringes of the policy debate. In addition to China’s Made in China 2025 initiative, the United Kingdom’s recently released Industrial Strategy, and a new Franco-German policy manifesto, Gulf Cooperation Council countries have also adopted strategies to develop non-oil sectors, and many developing countries are pursuing similar diversification efforts.

These policies have emerged as a response to pressures from international competition, a broad slowdown in productivity growth, manufacturing job losses, and rising inequality. But industrial policy has always stirred an intense debate among policymakers and academics. Critics argue that such strategies have not worked in many countries, and have instead resulted in cronyism and corruption. A better approach, they argue, is to reduce the role of the state in the economy, improve the business environment, and invest in infrastructure and education. Under favorable conditions, firms and entrepreneurs will emerge and grow in multitudes. The real-world failures of industrial policies in Latin America and elsewhere attest to the validity of this view.

In contrast, proponents of industrial policy argue that we live in a world of market failures that require some sort of state intervention. Otherwise, new sectors, especially advanced technology sectors, simply would not emerge, even in a good business environment. Naturally, this camp focuses on past successes, particularly in East Asian economies.

In a recent International Monetary Fund working paper, we use these past successes to identify three principles that underlie what we call a “true” industrial policy. In the Asian “miracle” economies – such as Singapore and South Korea – as well as in Japan, Germany, and the United States, the government intervened early on to support domestic firms in emerging, technologically sophisticated sectors. The successful policies placed special emphasis on export orientation, and held firms accountable for the support received. Given the strong focus on cutting-edge sectors, this “true” industrial policy is essentially a technology and innovation policy (TIP).

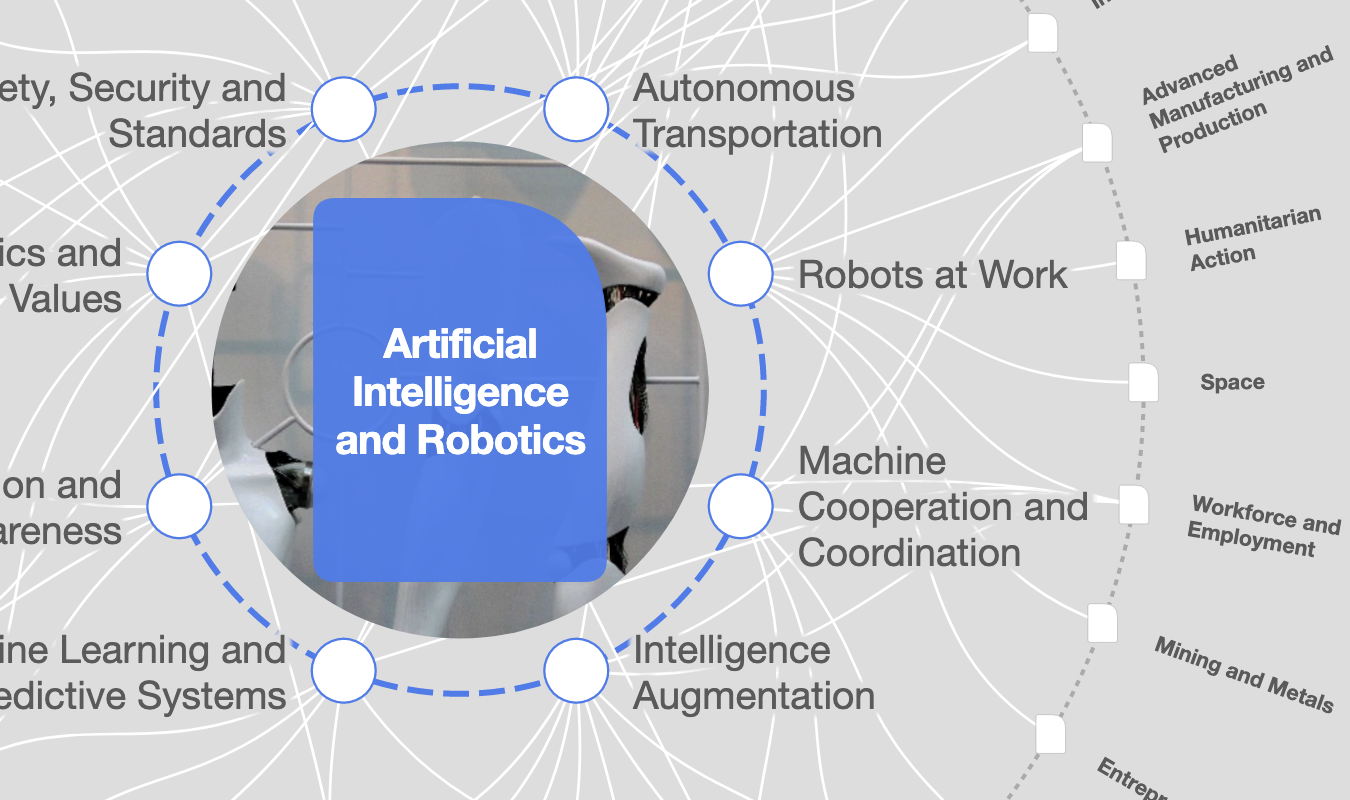

Technology and innovation are key to economic growth. China’s Made in China 2025 program essentially emulates the strategy used by South Korea (and Japan before it) to escape the so-called middle-income trap. Likewise, the new UK and Franco-German industrial strategies focus on the industries of the future: renewable energy, artificial intelligence, and robotics.

Capitalizing on the potential of disruptive innovation is an option for advanced and developing countries alike. Regardless of one’s place on the global value chain, producing cutting-edge technologies creates opportunities not only for domestic investors and businesses but also for consumers and industries elsewhere. Moreover, technological advances in the US, China, the UK, France, Germany, and other countries could be beneficial to all, contributing to competition, innovation, and living standards globally.

Just as it takes two wings to fly, both the state and the market are needed to implement an effective TIP. Indeed, “state vs. market” is precisely the wrong way to think about it. As we argued in our 2016 book Breaking the Oil Spell, the state must take the lead in steering resources toward activities that the market might not initially support on its own. At the same time, governments also must adhere to decision-making processes based on market signals, in order to guarantee space for an autonomous, competitive private sector. As economist Mariana Mazzucato argues, “When the public takes the lead and is ambitious, not just facilitating or being meek, it can push the frontier.”

As Mazzucato explains in The Entrepreneurial State, back when the US was dealing with the disappearance of New England’s old industries, it was also actively promoting technological innovation and spurring the creation of new sectors through public investment in research and development, as well as through government procurement policies. Indeed, in 1979, US federal government procurement accounted for over half of total purchases of aircraft, radio, and television equipment.

More broadly, there are many theoretical and empirical reasons for the state to support the maturation and commercialization of new technologies through public R&D, provision of risk capital, and investments in infrastructure and skills. Such outlays not only benefit existing innovation hubs, but also help to create new ones. The impact of state-led development is best illustrated by Kennedy’s call in 1961 for a moonshot: a seemingly impossible task became a reality by the end of the decade.

America’s drive to support technology and innovation has led to pathbreaking advances in science and disruptive technologies, and to the birth of the world’s leading high-tech industries. Following in its footsteps, many Asian economies have achieved economic miracles of their own by pursuing a “true” industrial policy. Now, all countries have a chance to find a niche in which to implement a TIP. If they succeed, the knowledge spillovers will benefit us all.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Emerging TechnologiesSee all

Kalin Anev Janse and José Parra Moyano

April 22, 2024

Sebastian Buckup

April 19, 2024

TeachAI Steering Committee

April 16, 2024

Maria Alonso, Markus Hagenmaier and Ivan Butenko

April 15, 2024