The post-pandemic planet: Will our relationship with the natural world really change?

What will the planet look like after the pandemic? Image: REUTERS/Clodagh Kilcoyne

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

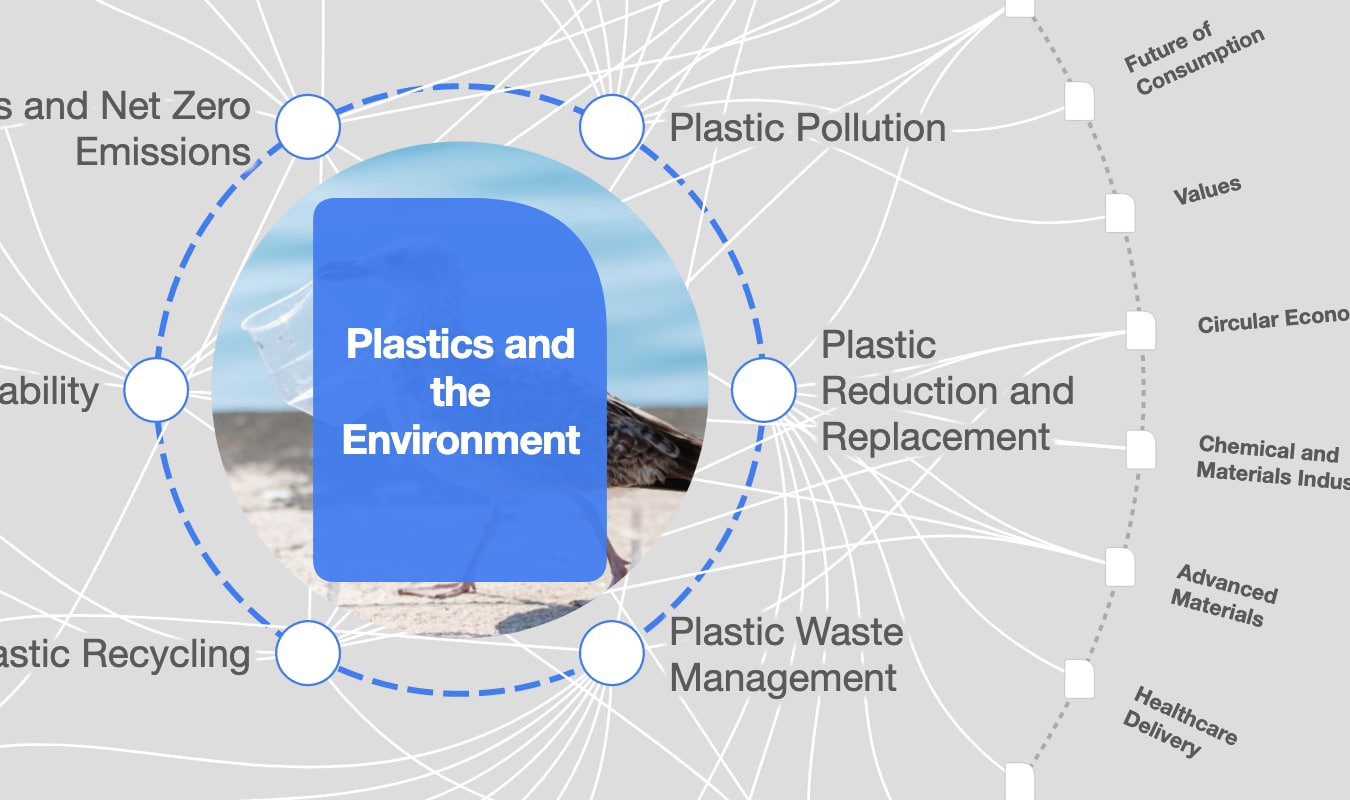

Plastics and the Environment

- Businessman and philanthropist André Hoffmann explores the ways our relationship to nature, and the environment, can change after the pandemic.

- He notes that green recovery packages tend to lead to a greater level of return, as well as well as ensuring long-term environmental protection.

- Hoffmann stresses the risk of deforestation, as it increases the likelihood of zoonotic diseases spreading from animals to humans.

Scientists have little doubt: the destruction of nature makes humanity increasingly vulnerable to disease outbreaks like the COVID-19 pandemic, which has sickened millions, killed hundreds of thousands, and devastated countless livelihoods worldwide. It also will impede long-term economic recovery, because more than half of the world’s GDP depends on nature in some way. Could the COVID-19 crisis be the wake-up call – and, indeed, the opportunity – we need to change course?

While some politicians have claimed that a pandemic of this scale was unforeseen, many experts believed that it was all but inevitable, given the proliferation of zoonotic diseases (caused by pathogens that jump to humans from other animals). More than 60% of new infectious diseases now originate in animals.

This trend is linked directly to human activities. From intensive farming and deforestation to mining and the exploitation of wild animals, destructive practices that we dismiss as “business as usual” place us in ever-closer contact with animals, creating the ideal conditions for disease spillovers. In this sense, Ebola, HIV, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) – all of zoonotic origin – were warnings the world failed to heed.

But COVID-19 could be different. After all, it has demonstrated more starkly than any of its predecessors just how fundamentally linked human health and prosperity are with the wellbeing of our planet – and how vulnerable that leaves us. Claims that protecting the environment would crash economies were not only shortsighted, but also counterproductive. It is environmental destruction that has ground the world economy to a halt.

Moreover, unlike previous recent disease outbreaks, COVID-19 has spurred unprecedented state intervention, with governments worldwide developing and implementing comprehensive recovery strategies. This provides a golden opportunity to entrench environmental protection and restoration in our economic systems.

Two principles should shape recovery strategies. First, stimulus alone is not enough; better environmental regulations, conceived with the active participation of business and investors, are also crucial. Second, public spending should be allocated in ways that support a better balance between the health of societies, economies, and the environment. This means investing in green industries, especially those that move us closer to a circular economy.

Leading economists such as Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern have found that green recovery packages would offer much higher rates of return, more short-term jobs, and superior long-term cost savings than traditional fiscal stimulus. For example, building clean-energy infrastructure – a particularly labor-intensive activity – would create twice as many jobs per dollar as fossil-fuel investments.

Other priorities include investment in natural capital, such as large-scale restoration of forest ecosystems. This would yield many valuable benefits, ranging from bolstering biodiversity and mitigating floods to absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. To complement such efforts, banks and other financial entities should be held responsible for lending practices that fuel the nature and climate crises.

Some decision-makers recognize this imperative. The International Monetary Fund has published broad guidance for a green recovery, and IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva has called for environmental conditions to be attached to corporate bailouts. The French government is already pursuing such an approach.

Furthermore, the European Union is drawing up a green COVID-19 recovery plan that would complement its European Green Deal, which aims to restore biodiversity and accelerate the shift to a zero-carbon economy. A group of 180 European politicians, companies, trade unions, campaign groups, and think tanks recently released a letter urging EU leaders to adopt green stimulus measures.

But, to achieve a sustainable global recovery, many more governments will have to embrace green-recovery policies. And, so far, many are doing the opposite, directing resources toward environmentally destructive industries and activities.

For example, according to the research involving Stiglitz and Stern, unconditional airline bailouts perform the worst in terms of economic impact, speed, and climate metrics. And yet billions are being channeled toward airlines, often with few strings attached.

In fact, according to a recent Green Stimulus Index report, more than a quarter of the stimulus spending implemented so far in 16 major economies is likely to cause substantial and lasting environmental damage. Some, such as US President Donald Trump’s administration, have also relaxed existing environmental rules, in order to help major polluters recover.

It is increasingly difficult to justify this approach. Lest we forget, just before the pandemic, countries were experiencing unprecedented wildfires and devastating flooding. As climate change advances, the extreme weather events that produce such disasters will become more frequent and severe.

Politicians and vested interests can try to divert attention from the challenges ahead. But this will not prevent future crises; it certainly won’t make them wait until the COVID-19 recovery is complete. On the contrary, a return to business as usual could hasten their arrival.

Rather than continue to stumble from one crisis to the next, we must build more resilient systems today. Putting environmental preservation and restoration at the center of the COVID-19 recovery is the perfect place to start.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Vincenzo Ventricelli

April 25, 2024

Shyam Bishen

April 24, 2024

Shyam Bishen and Annika Green

April 22, 2024

Johnny Wood

April 17, 2024

Adrian Gore

April 15, 2024