How cows could help solve the problem of plastic pollution

Not your average environmentalists. Image: REUTERS/Christinne Muschi

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Plastics and the Environment

- Bacteria found in cow stomachs can be used to digest polyesters used in textiles, packaging, and compostable bags, according to a new study.

- Plastic is notoriously hard to break down, but bacteria from a cow’s rumen, one of the four compartments of their stomach can digest it.

- The new findings present a sustainable option for reducing plastic waste and litter.

- The study has only been carried out at lab scale, but its authors believe the process would be easy to scale up, having significant environmental benefits.

Bacteria found in cow stomachs can be used to digest polyesters used in textiles, packaging, and compostable bags, according to a new study by the open access publisher Frontiers. Plastic is notoriously hard to break down, but microbial communities living inside the digestive system of animals are a promising but under-investigated source of novel enzymes that could do the trick. The new findings present a sustainable option for reducing plastic waste and litter, co-opting the great metabolic diversity of microbes.

Plastic is notoriously hard to break down, but researchers in Austria have found that bacteria from a cow’s rumen – one of the four compartments of its stomach – can digest certain types of the ubiquitous material, representing a sustainable way to reduce plastic litter. The discovery is published today in the open access journal Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology.

The scientists suspected such bacteria might be useful since cow diets already contain natural plant polyesters. “A huge microbial community lives in the rumen reticulum and is responsible for the digestion of food in the animals,” said Dr Doris Ribitsch, of the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna, “so we suspected that some biological activities could also be used for polyester hydrolysis,” a type of chemical reaction that results in decomposition. In other words, these microorganisms can already break down similar materials, so the study authors thought they might be able to break down plastics as well.

Ribitsch and her colleagues looked at three kinds of polyesters. One, polyethylene terephthalate, commonly known as PET, is a synthetic polymer commonly used in textiles and packaging. The other two consisted of a biodegradable plastic often used in compostable plastic bags (polybutylene adipate terephthalate, PBAT), and a biobased material (Polyethylene furanoate, PEF) made from renewable resources.

They obtained rumen liquid from a slaughterhouse in Austria to get the microorganisms they were testing. They then incubated that liquid with the three types of plastics they were testing (which were tested in both powder and film form) in order to understand how effectively the plastic would break down.

According to their results, all three plastics could be broken down by the microorganisms from cow stomachs, with the plastic powders breaking down quicker than plastic film. Compared to similar research that has been done on investigating single microorganisms, Ribitsch and her colleagues found that the rumen liquid was more effective, which might indicate that its microbial community could have a synergistic advantage – that the combination of enzymes, rather than any one particular enzyme, is what makes the difference.

While their work has only been done at a lab scale, Ribitsch said, “Due to the large amount of rumen that accumulates every day in slaughterhouses, upscaling would be easy to imagine.” However, she cautions that such research can be cost-prohibitive, as the lab equipment is expensive, and such studies require pre-studies to examine microorganisms.

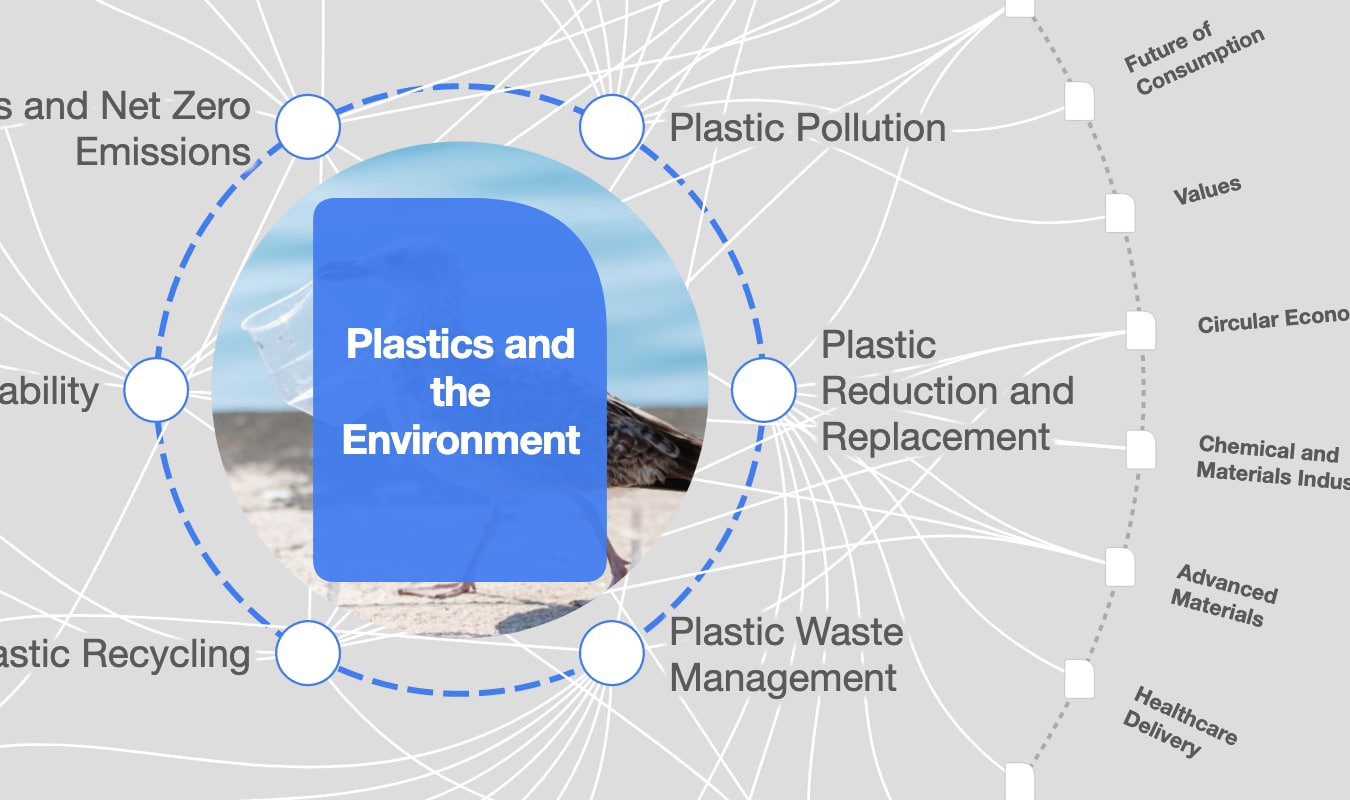

What is the World Economic Forum doing about plastic pollution?

Nevertheless, Ribitsch is looking forward to further research on the topic, saying that microbial communities have been underexplored as a potential eco-friendly resource.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

Dan Lambe

April 24, 2024

Roman Vakulchuk

April 24, 2024

Charlotte Kaiser

April 23, 2024

Jennifer Holmgren

April 23, 2024

Agustin Rosello, Anali Bustos, Fernando Morales de Rueda, Jennifer Hong and Paula Sarigumba

April 23, 2024

Carlos Correa

April 22, 2024