5 factors limiting the impact of the BRICS nations

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Russian Federation

The BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa – now represent 3 billion people and a combined GDP of 16 trillion dollars. The group is the ‘third giant’ after the EU and the US. But BRICS member nations are too different, and have too few synergies, to represent a solid economic and political power.

- The dominance of the Chinese economy and its role in trade relations makes the BRICS much more a China-with-partners group than a union of equal members.

- BRICS countries lack mutual economic interests. Trade between them is now less than 320 bln dollars a year and declining. Their trade with the US and EU is 6.5 times higher. China’s trade with the rest of the world is 12.5 times higher. Bilateral trade between China and South Korea is almost as large as that between BRICS nations.

- Members are too similar in some key areas. All members (apart from Russia) hold huge foreign reserves (15-35% of GDP) and have low external debt (15% to 37% of GDP.) Apart from Russia, they are heavily integrated into consumer goods production with the ‘West’.

- BRICS nations compete in third markets. In many areas, from clothing (China, India and Brazil), through economic influence in Africa (China, South Africa and India) to international aircraft and military equipment markets (China, Russia and Brazil) BRICS countries compete with one another. All are able to re-engineer and copy technologies, which means sharing R&D results and innovations and the development of cross-country scientific cooperation has limited potential.

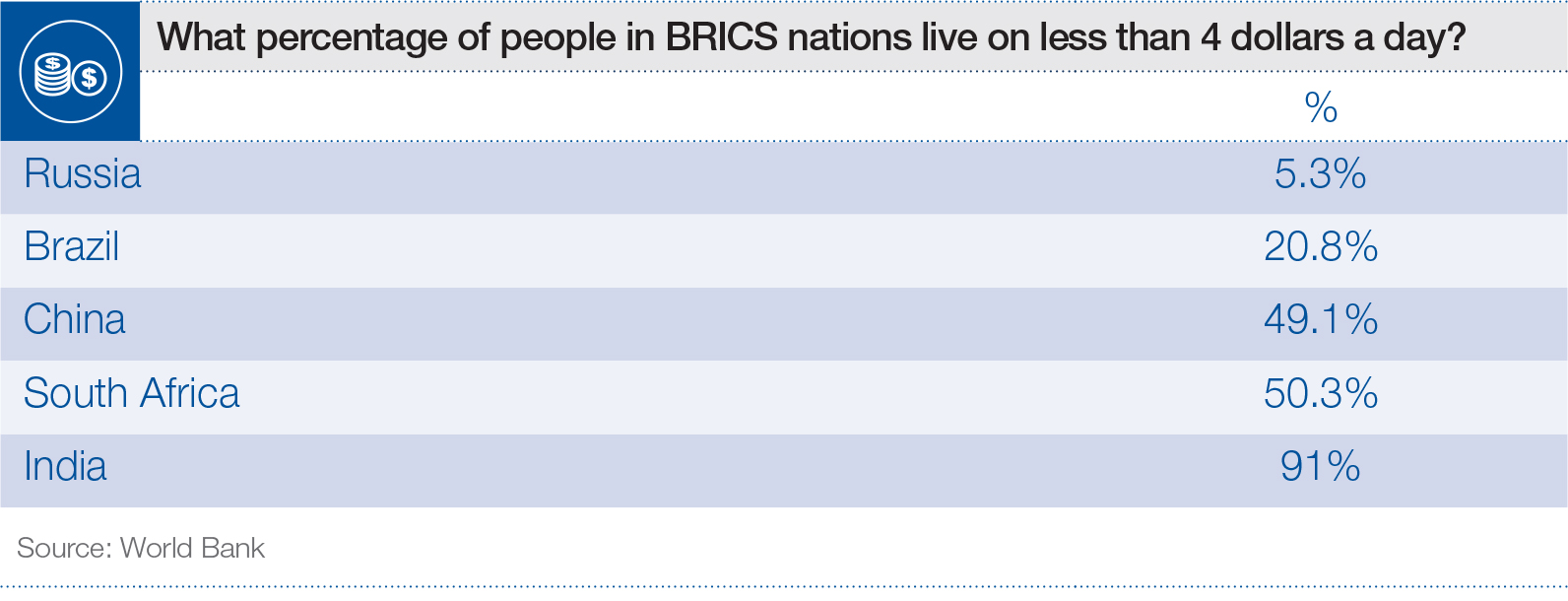

- Diversity of cultures. Phases of economic development, ideologies, definitions of poverty and other cultural differences mean BRICS members lack common understandings about priorities that are necessary for productive sharing of experiences.

While a union of BRICS is undoubtedly positive, its role as the ‘third economic power’ should not be overestimated. For most members the bloc represents a means to discuss opinions and perhaps take a joint position on any areas of mutual interest. China views the organization as a useful test-bed for its ambitious development ideas, while Russia alone sees the possibility of mobilizing finance from a new channel.

The Russian economy is in its third year of decline, and with no meaningful programme for turning things around, currency reserves may start falling fast enough to require Moscow to seek external financing. Having alienated major powers with recent actions, and despite its role as a source of energy for developed nations, Russia’s ability to borrow from the developed world is at an end.

Russia is the only BRICS member dependent on resources (18% of GDP, more than 50% of the federal budget) and the recent dramatic drop in both oil prices and demand for natural gas, has cut the value of Russian exports by 30% over the past year. Against this backdrop, Russia sees BRICS as a potential source of funding and economic aid – an alternative to the US-led IMF and EBRD/IFC – and insensitive to political issues.

Trapped between political alienation with the ‘West’ and deep dependence on it for markets and finance, Russia needs an intermediary able to represent and support it in discussions with opponents. BRICS is viewed as such an intermediary and one that can be used to demonstrate to a domestic audience that Russia is not really isolated.

Unfortunately for Russia, its expectations are too great. Even in the unlikely case that all members were to direct all financial resources to Russia, they would not cover its needs. Intermediation between Russia and the West by BRICS is also hard to imagine: other BRICS countries will not risk their relations with the US and EU for the sake of weak and potentially loss-making relations with Russia. And the illusion of safety given to the Russian public by BRICS membership will, as any false hope does, only worsen the situation if and when the country is hit by new storms.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Andrey Movchan is Head of Economic program, Carnegie Foundation for peace and prosperity, Moscow center

Image: An employee cleans a board during the preparations for the BRICS summit in Ufa, Russia. REUTERS/BRICS Photohost/RIA Novosti

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Global CooperationSee all

Aba Schubert

April 26, 2024

Kiriko Honda

April 25, 2024

Lasse Jonasson

April 24, 2024

Tunde Kara

April 24, 2024

Ella Yutong Lin and Kate Whiting

April 23, 2024

Spencer Feingold and Kate Whiting

April 23, 2024