How to make a machine hear like a human

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Emerging Technologies

People trying to talk to Siri may soon no longer have to look like they’re about to eat their iPhones, thanks to a new technology demonstration that solves the “Cocktail Party” conundrum.

In a crowded room with voices coming from every direction, the human auditory system is incredibly good at homing in on a single voice while filtering out the background jabber.

Computers are not.

A new approach from engineers at Duke University, however, may soon improve their performance in loud environments. The sensor uses metamaterials—the combination of natural materials in repeating patterns to achieve unnatural properties—and compressive sensing to determine the direction of a sound and extract it from the surrounding background noise.

The study was featured in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on August 11, 2015.

“We’ve invented a sensing system that can efficiently, reliably and inexpensively solve an interesting problem that modern technology has to deal with on a daily basis,” said Abel Xie, a PhD student in electrical and computer engineering at Duke and lead author of the paper. “We think this could improve the performance of voice-activated devices like smart phones and game consoles while also reducing the complexity of the system.”

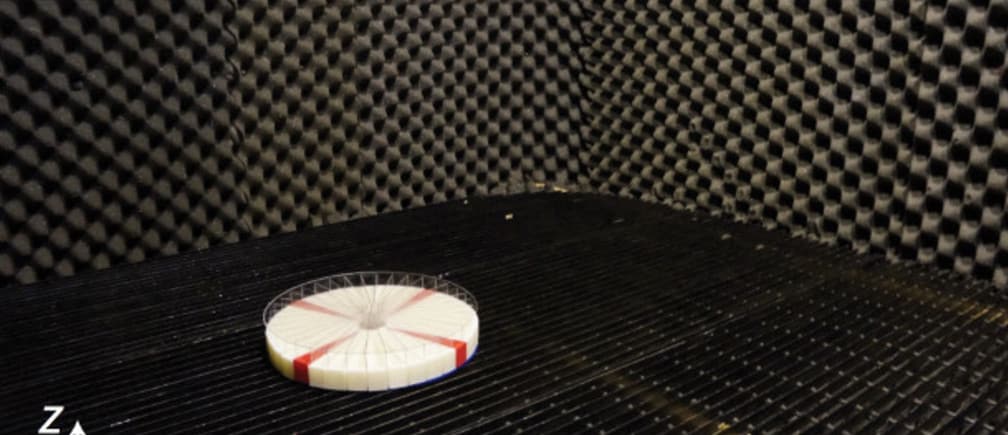

The proof-of-concept device looks a bit like a thick, plastic, pie-shaped honeycomb split into dozens of slices. While the honeycomb openings may all look the same, their depth varies from hole to hole. This gives each slice of the honeycomb pie a unique pattern.

“The cavities behave like soda bottles when you blow across their tops,” said Steve Cummer, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Duke. “The amount of soda left in the bottle, or the depth of the cavities in our case, affects the pitch of the sound they make, and this changes the incoming sound in a subtle but detectable way.”

When a sound wave gets to the device, it gets slightly distorted by the cavities. And that distortion has a specific signature depending what slice of the pie it passed over. After being picked up by a microphone on the other side, the sound is transmitted to a computer that is able to separate the jumble of noises based on these unique distortions.

This prototype sensor can separate simultaneous sounds coming from different directions using a unique distortion given by the slice of “pie” that it passes through.

This prototype sensor can separate simultaneous sounds coming from different directions using a unique distortion given by the slice of “pie” that it passes through.

The researchers tested their invention in multiple trials by simultaneously sending three identical sounds at the sensor from three different directions. It was able to distinguish between them with a 96.7 percent accuracy rate.

While the prototype is six inches wide, the researchers believe it could be scaled down and incorporated into the devices we use on a regular basis. And because the sensor is made of plastic and does not have any electric or moving parts, it is extremely efficient and reliable.

“This concept may also have applications outside the world of consumer electronics,” said Xie. “I think it could be combined with any medical imaging device that uses waves, such as ultrasound, to not only improve current sensing methods, but to create entirely new ones.

“With the extra information, it should also be possible to improve the sound fidelity and increase functionalities for applications like hearing aids and cochlear implants. One obvious challenge is to make the system physically small. It is challenging, but not impossible, and we are working toward that goal.”

This work was supported by a Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative under Grant N00014-13-1-0631 from the Office of Naval Research.

This article is published in collaboration with Duke. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Ken Kingery is a science writer for Duke.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Emerging TechnologiesSee all

James Fell

April 26, 2024

Alok Medikepura Anil and Uwaidh Al Harethi

April 26, 2024

Thomas Beckley and Ross Genovese

April 25, 2024

Robin Pomeroy

April 25, 2024

Beena Ammanath

April 25, 2024

Vincenzo Ventricelli

April 25, 2024