Fake news: Can kids be taught to spot it?

Students are now being encouraged to examine the sources, verify facts and flag up fabricated stories to relevant authorities. Image: REUTERS/Michael Kooren

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Media, Entertainment and Sport

More than 2 million people have shared, commented on and reacted to a story that former president Barack Obama had signed an executive order banning schoolchildren from taking the pledge of allegiance.

The story is – as many of you readers will have guessed – completely untrue.

It was first posted on a site called ABCNews.com.co – a fake site made to look like ABC News. And it has the dubious distinction of being the most widely shared piece of fake news last year, according to BuzzFeed.

Meanwhile, during last year’s US election campaign, fake news was circulated almost 40 million times according to research from Stanford University, including claims that the Pope had endorsed Donald Trump and the terrorist group Daesh had endorsed Hillary Clinton.

Now Italy, facing elections of its own next year, has taken a preemptive strike against the spread of fake news through its education system.

“Fake news drips drops of poison into our daily web diet and we end up infected without even realizing it,” said the Italian politician Laura Boldrini who is spearheading a project with the Italian Ministry of Education to teach school children how to spot fake news.

“It’s only right to give these kids the possibility to defend themselves from lies,” she told the New York Times.

The initiative will be rolled out in 8,000 high schools across the country, with students encouraged to examine the sources, verify facts and flag up fabricated stories to the relevant authorities.

Some fake news hoaxes – you can charge an iPhone by popping it in the microwave, for example – should be easy to spot if students are taught to check sources rather than just skim read and to think twice (or maybe just once) before sharing an article.

But the dark arts of disseminating misinformation are increasingly sophisticated and, in the case of Russian interference in the US election, require an FBI investigation rather than a lesson at school to untangle.

Politics is especially susceptible to persistent, coordinated and well-disguised campaigns which spread fake news.

The deliberate spreading of false information has played its part in the UK’s referendum on whether to stay in the EU, the upcoming elections in Kenya and the animosity between presidential candidates Marine le Pen and Emmanuel Macron in France.

In fact, it is only in countries with strict internet censorship where fake news is not expected to enter the fray of daily politics.

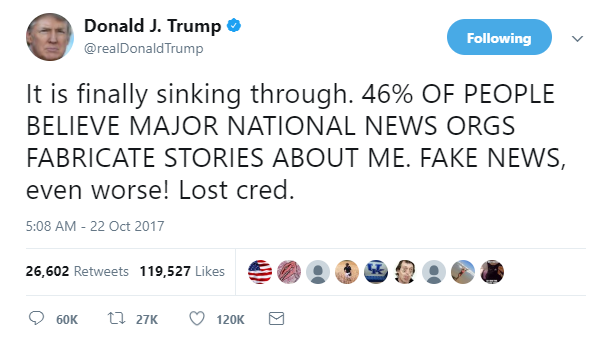

Politicians often complain about being the victims of fake news.

The Spanish foreign minister told the BBC that many of the pictures showing police violence against Catalan voters were fake news. And US President Donald Trump is consistent in his criticism of the media for spreading fake news.

But that in turn causes some people to worry that politicians themselves could use the existence of fake news to get rid of inconvenient stories.

Social media firms such as Facebook and Twitter are grappling with how to police the content of their sites. And governments around the world are wrestling with how to legislate against it.

But while training schoolchildren to try to spot it may be a good start, fake news stories aren't likely to disappear anytime soon.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Industries in DepthSee all

Robin Pomeroy

April 25, 2024

Daniel Boero Vargas and Mandy Chan

April 25, 2024

Abhay Pareek and Drishti Kumar

April 23, 2024

Charlotte Edmond

April 11, 2024

Victoria Masterson

April 5, 2024

Douglas Broom

April 3, 2024