3 charts that show who pays most for the defence of Europe

Rather than simply spending more, European allies could improve the efficiency of their investment in defence Image: REUTERS/Ints Kalnins

This article is part of the World Economic Forum's Geostrategy platform

Global defence spending in 2018 amounted to over $1.67 trillion – up more than $80 billion on the previous year and reflecting higher spending in Western states, notably the United States, according to data in the IISS report, The Military Balance 2019.

Indeed, the US has driven the global rise in spending, with a 5% real-terms budget increase between 2017 and 2018. In 2018, the US accounted for 45% of the global increase in defence spending, in constant 2010 dollars.

European spending: still not enough?

The nominal increase in US defence spending ($44.5bn in 2018 dollars) was the largest increase in the world in 2018 – far above China, which was the second largest at $16.7bn. It almost amounted to Germany’s total defence outlays in 2018.

However, European nations also contributed to the global trend. After years of reduced spending after the end of the Cold War and in the wake of the financial crisis, NATO’s European member states increased their defence budgets by 4.2% in real-terms in 2018.

Their total spending would – if the aggregate figure of $264bn were considered on its own – amount to the second largest defence budget in the world. It would be equivalent to 1.5 times China’s official budget ($168bn), and almost four times Russia’s estimated total military expenditure ($63bn). (Canada sits just outside the top 15, in 16th place with $18.2bn.)

Yet this is still deemed insufficient by some, with Europeans in particular being accused by the Trump administration of not doing enough for their own security.

One quick way to measure European contributions to collective defence is to calculate how much of their GDP they dedicate to military expenditure. As measured by the IISS, in 2018 only four out of the 27 European NATO member states met the 2% symbolic threshold: Estonia, Greece, Lithuania and the United Kingdom.

Four countries were not far behind: France (1.91%), Latvia (1.99%), Poland (1.97%) and Romania (1.93%).

Based on 2018 budgets, NATO European members would have had to spend an extra $102bn, on top of their existing budgets, in order to spend 2% of GDP on defence.

This gap has narrowed in comparison to 2014, when the 2% pledge was made at NATO’s Wales summit. Then, they would have had to spend an extra $112bn. The Wales pledge was to ‘move towards’ 2% spending over ten years. On current trends, NATO’s European members will – as a whole - still be shy of that target by 2024. But while the percentage of GDP spent on defence may be a quick way to measure contributions, it is also a rather imprecise measure. Because the 2% target is a ratio based on GDP, if GDP grows the target is harder to reach. Conversely, when GDP contracts – as in the post-2008 period – the threshold is easier to reach.

In the meantime, US President Donald Trump has raised the rhetorical pressure on Washington’s European allies, saying they should actually spend up to 4% of their GDP on defence. Despite Trump’s suggestion to the contrary, that is a benchmark the US itself does not match (3.1% in 2018 according to the IISS; 3.50% according to NATO).

US commitments to European defence, 2018

This discussion of burden-sharing raises an additional question: how much does Washington spend on Europe’s defence? Since 2017, the IISS has estimated US outlays on European defence by examining three categories:

- Direct funding for NATO as an organisation, including common procurements and missile defence. This amounted to $6.74bn in 2018.

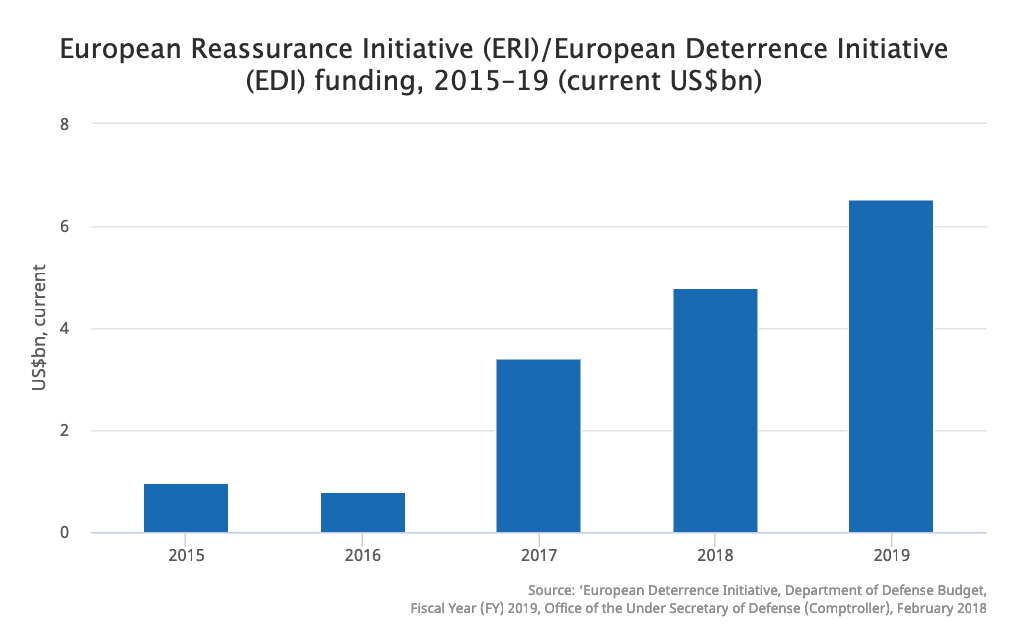

- The costs of the US military presence in Europe, including the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI). The EDI budget was $789 million in 2016 but rose to $4.78bn in 2018 and is projected to increase to $6.53bn in 2019. Overall, counting personnel costs and operating bases, US military presence in Europe is estimated at $29.1bn in 2018.

- US foreign military financing (FMF). The US has significantly reduced FMF funds, and a smaller number of countries now receive FMF, part of the State Department budget (major recipients include Egypt and Israel). In 2018, no European country received FMF funds.

Altogether, the estimated direct US expenses on defence in Europe reached $35.8bn in 2018, or around 5.6% of total US ‘national defense function’ outlays that year. These numbers put the total defence spending by European NATO states – the $264bn mentioned above – in a different light.

Of course, in policy terms, this does not account for the totality of the US commitment to Europe. In the event of a major contingency, such as against Russia, this would also involve significant reinforcement from the continental US; it also encompasses the US nuclear umbrella. But, given Washington’s other global commitments, attributing to European defence the entirety of the $643bn 2018 US defence outlay would equally seem to overstate the US commitment. (If one were to employ this rationale on Europe’s spending, a proportion of French and UK spending would also have to be attributed to their global commitments.)

More efficient and cooperative spending

The arguments over burden-sharing are not new and will evolve alongside changes to national threat perceptions and budgets. At the same time, amid rising populism and social discontent, decisions to dedicate more national resources to defence will likely be carefully weighed against other policy priorities.

With this in mind, it is worth recalling the defence-investment pledge made in Wales in 2014. This indicated that, alongside the 2% goal, allies agreed ‘to make the most effective use of our funds’. As such, simply spending more on defence may not necessarily be the optimum outcome; rather, allies could at the same time sharpen their focus on spending their defence funds more effectively. For instance, European states could improve the ‘value for money’ of their defence investments.

One way of doing this would be by spending better together. Of course, the practical benefit of this depends on the degree to which their defence-equipment requirements can be aligned and how much states decide to reduce duplication across their defence capabilities; perhaps as a consequence deepening their mutual interdependence.

Where such alignment exists, and where countries are willing to adjust previous imperatives relating to factors like industrial workshare, common procurements could lead to economies of scale.

A sign of European states’ commitments to taking their part in burden-sharing is the future €13bn ($15.4bn) for defence they are looking to include in the next European Union budget. This will fund defence-research and joint defence-industrial projects. Amid continued calls from across the Atlantic for more spending ‘tout court’, Europe’s smart response should begin with more efficient spending.

On the up: Western defence spending in 2018, Lucie Béraud–Sudreau, the International Institute for Strategic Studies

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

United States

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Resilience, Peace and SecuritySee all

Shoko Noda and Kamal Kishore

October 9, 2025