Q&A: The changing role of the United States in a shifting geopolitical landscape

The United States has many residual strengths and is able to sustain its pre-eminent position Image: REUTERS/Jim Young

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

United States

Global trends, including shifting balances of power, growing nationalism, and the emergence of new digital battlefields, are reshaping the geopolitical landscape.

What do these developments mean for the U.S. position as the world’s leading power and will Washington look to maintain its position of influence in the world?

To answer these questions, the World Economic Forum spoke with Michael Mazarr, senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation.

You recently wrote in Foreign Affairs that the United States is “showing signs it no longer values its role as leader”. Is Pax Americana coming to a close?, and where do you see the U.S. in the next 10 or 20 years in terms of global power and influence?

No, I don’t think so. Many recent actions have signaled that the United States no longer values leadership in the same way, and have been counterproductive to long-term U.S. influence. But the United States has many residual strengths. Its military is still predominant and faces challenges only in relation to a few exceptionally demanding contingencies.

Washington has the world’s reserve currency and dominates global financial networks. But more than that, the United States remains the hub of a network of free, open, democratic, economically developed or rapidly developing states which share important values and many objectives. And its liberal, democratic, relatively tolerant, market-based system, shared by many friends and partners, has historically proven more efficient and productive than any rivals.

China’s strengths are considerable, but are also being exaggerated at the moment; and its weaknesses—such as the absolute lack of any sort of appealing narrative of values and political principles to offer—will end up being quite constraining.

In a sense, anything like a truly absolute “Pax Americana” existed for a vanishingly short period of time anyway. It is coming to an end, but only in its most extreme unilateralist form.

A period in which the U.S. is the clear primus inter pares in the world community, and the recognized leader of the value-sharing democratic (and democracy-aspiring) world, need not be over, or close to over.

But for U.S. leadership to be put on a sustainable footing, two very difficult things must happen. Domestically, the United States must find a route to some politically painful and economically costly reforms, and do so amid a populist surge that has boosted polarization and mistrust.

And internationally, the United States must embrace a more shared vision of the shared order, allowing friends, allies and partners to have larger voices in the operation of that order. Neither is guaranteed.

But the critical thing, to me, is that the factors holding the United States back are the products of policy choices, not systemic issues. China’s handicaps, as a comparative example, are far more essential to its system.

Nationalist trends have gained ground in many countries – do you see this as a serious threat to a broad cooperative international framework?

Yes, absolutely, and indeed these trends are most serious threat to a stable international system. The United States confronts two epochal historical trends: the rise of China, and the most significant global challenge to the reigning neoliberal socioeconomic model. That socioeconomic challenge, as has been widely discussed, is the product of such things as inequality, stagnant wages and economies, the power of large and unaccountable institutions, and urgent ecological challenges led by climate change.

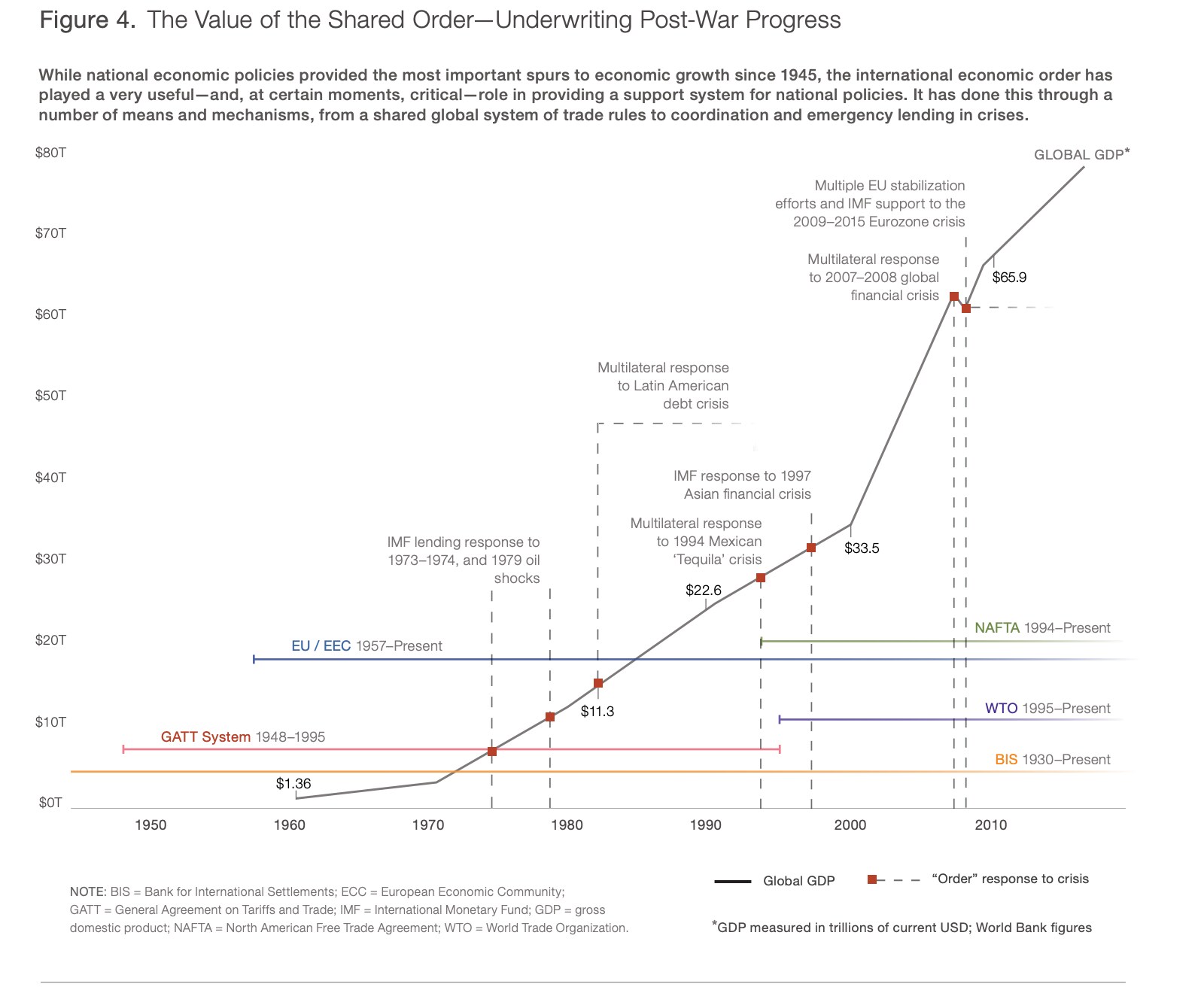

The resulting waves of populism, nationalism, and loss of faith in existing institutions have the potential to rip the liberal order apart from the inside. The evidence of the results is everywhere, from threats to multinational organizations like the EU and international institutions like the WTO to rising tension and hostility to confrontational ethno-nationalist visions.

If that trend continues unabated, it will not really matter what the U.S. defence budget is or how capable its weapons systems are—the world system as we have known it will become far less coherent and far more dangerous. Dealing constructively, powerfully and seriously with the very legitimate objections to the neoliberal model thus stands as the most essential step toward international stability and continued U.S. leadership of a coherent order.

The China challenge is getting a lot of the attention; the socioeconomic crisis is ultimately far more fundamental and potentially decisive.

Much of what drove great power competition in the past was military strength. Are cyber-attacks and trade wars the new battlefields?

Absolutely, those and related areas. Large-scale warfare remains possible, through miscalculation or escalation. But especially among the big powers, the risk of nuclear conflict, U.S. conventional superiority (in general terms) and other factors mean that we’re not likely to see large-scale territorial aggression.

China and Russia want to achieve their goals short of that—by using information manipulation, economic aid and investment, cyber attacks, political subversion, and many other tools.

In particular, I am worried about how societies’ information environments are becoming so networked and vulnerable through such mechanisms as the emerging Internet of Things and the more common use of algorithmic decision making. All of that can be hacked and disrupted, either very gradually or all at once.

But preparing for these 21st century conflicts demands integrated planning and actions from military, informational, economic and other agencies of government—a really tough act to pull off.

You’ve examined some of the errors that led to the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, but said Washington could be pulled into a similar conflict again. What are the biggest blind spots Washington needs to correct to avoid repeating mistakes of the past?

I would say it’s not so much avoiding blind spots as it is being willing to rethink basic assumptions about the way the nation goes to war.

I have argued that the decision making process for the Iraq war was poisoned by several things—bad assumptions about weapons of mass destruction and the character of Iraqi society, to be sure, but also by an unquestioned assumption of America’s missionary role, the idea that the United States had the right and more than that the obligation to deal with any major security issue.

An era of greater competition also demands a more prudent, rigorous and constrained U.S. approach in going to war, in part because the risks are so much higher.

”Ultimately, this was manifest in a sense of obligation or imperative that meant the decision makers weren’t even thinking about risks or costs in any meaningful way.

Paradoxically, I think that an era of greater competition also demands a more prudent, rigorous and constrained U.S. approach in going to war, in part because the risks are so much higher.

In the Iraq case, the U.S. media, Congress, and senior executive branch officials all failed in their duty to interrogate the proposed course of action. There’s no evidence that anything has decisively changed since then.

I don’t believe in visions of large-scale U.S. retrenchment. But I do think that sustainable U.S. leadership is going to demand a greater degree of restraint—arguably the toughest balancing act that the United States has ever had to make.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Resilience, Peace and SecuritySee all

Lisa Satolli

April 18, 2024

Kate Whiting

April 4, 2024

Spencer Feingold

March 22, 2024

Weekend reads: Our digital selves, sand motors, global trade's choke points, and humanitarian relief

Gayle Markovitz

March 15, 2024

Kalkidan Lakew Yihun

March 11, 2024

Liam Coleman

March 7, 2024