Scientists find plastic pollution in the rain and in the air we breathe

Plastic pollution is a major problem worldwide Image: REUTERS/Zohra Bensemra

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

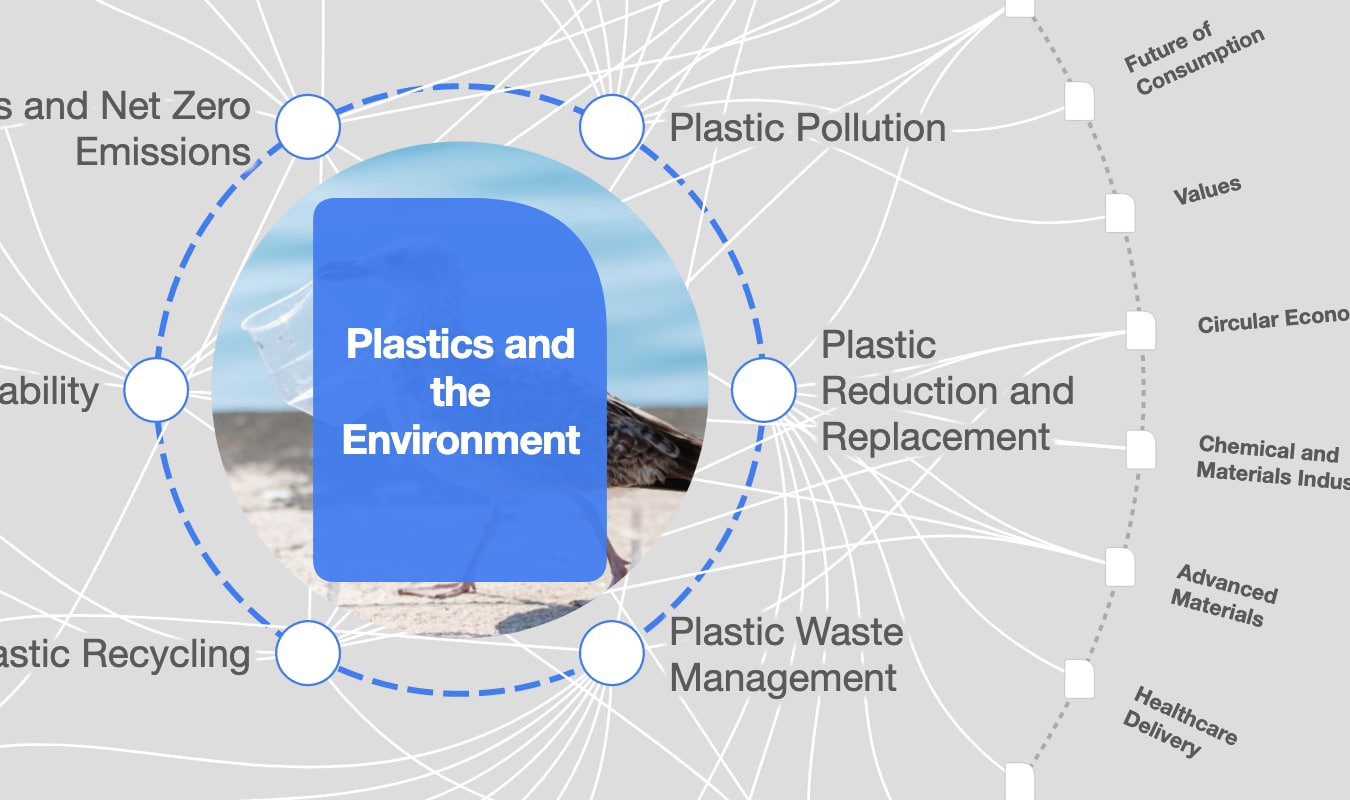

Plastics and the Environment

- Researchers in the US have found enough plastics

- to make over 120 million bottles fell to Earth in just 11 sites.

- It’s breaking down in particles so small you could be breathing them in.

- There could be 11 billion tonnes of environmental plastics by 2025.

If you saw 120 plastic bottles fall from the sky, you’d be right to feel concerned. But what if that number was multiplied by a million?

That’s equivalent to the amount of microplastics that fall on just 11 national parks and wilderness areas in the United States annually, according to new research – more than 1,000 tonnes in those areas alone.

Some of those plastics are so tiny you can’t see them. But you can breathe some of them in. You probably already have.

Writing in the journal Science, the report’s authors warn that 11 billion tonnes of plastics will accumulate in the environment by 2025.

The great outdoors

The team of researchers, led by a Utah State University scientist, collected samples of air and rainwater from 11 sites in the western part of the US. They found unexpectedly large quantities of microplastics had fallen in the rain and were being carried in the air.

Over the course of the year, 98% of the samples they collected contained tiny, sometimes microscopic particles of plastics.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the tiniest particles were those carried by the wind – larger ones were typically found in the collected water. The implications of that finding alone are a clear indication of the widespread problem of plastics that are not being disposed of responsibly.

One of plastics' greatest attributes has turned out to be their greatest curse too – it’s so resilient and long-lasting that it is hard to get rid of. Whether it’s a bottle, bag, or burrito wrapper, plastic doesn’t decompose, it fragments. A single plastic item can eventually be transformed into countless pieces of microplastics.

Discarded as litter, plastic pollution also frequently finds its way into many of the world’s major rivers, eventually being carried out to sea.

Microplastics have been found on the seabed and in Arctic sea ice. They are in rivers and lakes, on top of mountains, in desert sand dunes, and maybe even in the food chain. In 2019, researchers found fibres and microplastics on eight Spanish beaches that have special protection status under the EU Habitats Directive and Birds Directive.

This isn’t the first time microplastic pollution has been found in protected natural areas. In 2014, particles were found on 125 beaches on three of the Canary Islands: Lanzarote, La Graciosa, and Fuerteventura. As much as 100g of plastics were detected per one litre of sand.

It has also been found in the South Pacific and North Atlantic, on the lowest point on Earth (the Mariana Trench, 11km below the surface of the Pacific Ocean), and at the highest point, Mount Everest.

In short, it’s everywhere. It has even been detected in human faecal matter.

While the World Health Organization has said that microplastics in drinking water don't appear to pose a problem to human health based on the limited information available, it has called for more research and a clampdown on plastic pollution.

From micro to nano, it’s a growing problem

Any particles smaller than approximately 5mm are deemed to be microplastics. Smaller still are nanoplastics, which can be as small as one-millionth of a millimetre. Some of these are purposefully produced and used in a range of domestic and industrial applications, from cosmetic products to diagnostic work. Others are the result of plastic erosion.

Some of these particles are so tiny that even those that have found their way into the sea can be whipped up into the air by the wind and carried vast distances. High altitude air currents carry them across thousands of kilometres, while some adhere to rain-forming clouds.

Those that remain in the sea are believed to be entering the food chain, too. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization: “Ingestion of microplastics by aquatic organisms, including species of commercial importance for fisheries and aquaculture, has been documented in laboratory and field studies.”

The extent to which this is harmful to humans is unclear. The UN also states that potentially harmful effects of ingested plastics on marine creatures have so far only been detected under laboratory conditions. Even then, only when plastic concentrations were high.

For the most part, people only eat fish that have had their gastrointestinal tracts removed first. That could minimize the potential for microplastics being passed from fish to person. But it’s not always the case. Molluscs such as mussels, clams, scallops and oysters are eaten whole, as are many small fish species.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Food and WaterSee all

Pooja Chhabria and Michelle Meineke

April 28, 2024

Abhay Pareek and Drishti Kumar

April 23, 2024

Johnny Wood

April 15, 2024

Charlotte Edmond

April 11, 2024

Brian D’Silva and Abir Ibrahim

March 19, 2024