A vision for post-pandemic mobility in African cities

COVID-19 has shown us that car-oriented cities are the least efficient Image: Sindile Mavundla

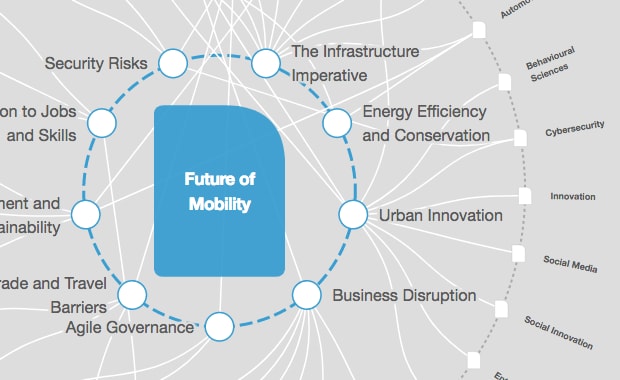

Explore and monitor how Mobility is affecting economies, industries and global issues

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Mobility

- The traffic-free measures taken by cities across the globe during the pandemic are still absent in many African cities.

- But transport infrastructure built with non-vehicular mobility in mind could transform cities for the better in the aftermath of COVID-19.

- Several cities, from Cape Town to Kampala, offer a glimpse of how urban mobility might look in Africa's near future.

Cycling lanes and walkways are popping up in cities across the globe, from Bogotá to Paris to Jakarta, and even in car-centric cities such as Los Angeles and Sydney, as pandemic-calming measures that ensure physically distanced movement. However, across African cities, where pedestrians and public transit users often occupy the vast majority of urban mobility, such infrastructure continues to be conspicuously absent.

Beyond the everyday ills of car-dominant cities – polluted skies, traffic jams and deadly vehicle accidents, for example – “the pandemic has shown us that unplanned, inaccessible and car-oriented cities are the least resilient”, says Iman Abubaker, Urban Mobility Project Manager at WRI Africa Ross Centre for Sustainable Cities.

In cities from Accra to Nairobi, Dakar to Addis Ababa, and Dar es Salaam to Lagos, pedestrians, cyclists, public and collective transport users dominate the streets. “In spite of this high level of non-motorised mobility, street space is disproportionately allocated to motorised vehicles,” Abubaker adds.

Beyond excluding the non-motorised majority, such designs bode poorly for public health. In fact, a recent study in East Africa depicts the unhealthy levels of urban air quality in Addis Ababa, Kampala and Nairobi, largely due to vehicular emissions.

The global decrease in road traffic can be the impulse for African cities to leapfrog into transport infrastructures that reflect realities on the ground. This can happen by avoiding street designs based on highways and sprawling roads (or at least disincentivizing them in places where such design has been embraced and even become mainstream) for a dominant motor vehicle class that does not exist.

Beyond car-free streets

More than just a key ingredient to pandemic survival recipes, Open Streets - meaning the temporary creation of car-free streets – could be a vital element in how we thrive post-pandemic. With the onset of COVID-19, Open Streets has taken on a new meaning that retains its car-free nature but focuses on the need for physical distancing.

However, the global Open Streets movement can do much more than this. It can provide the impetus for rooting our cities in equitable and sustainable transport systems that are grounded in spatial justice and designed for the majority.

Open Streets programmes, inspired by Bogotá's Ciclovía, have gained in popularity in hundreds of cities worldwide, including African cities like Cape Town, Abuja, Kigali and Addis Ababa, where active mobility and collective transport dominate. At its core, the initiative advocates for cities grounded in non-motorised transport (NMT), sustainable mobility and cohesive communities. This enables a change in “how streets are perceived, invested, used and experienced”, says Engineer Emmanuel John, principal organiser at Abuja Open Streets.

In Latin America, where the concept has been rolled out on a weekly basis for decades and serves as a social platform for people to interact and exercise in large numbers, programmes have been suspended because they tend to attract large crowds. In cities like Bogotá for instance, prior to COVID-19, over 1 million inhabitants would take to the streets to cycle, run, take part in organised mass exercise classes and enjoy the car-free space every Sunday. During a pandemic, enforcing physical distance and sanitation measures in such activities is a real challenge. Likewise, smaller and younger initiatives across the African continent have been brought to a halt. Nevertheless, the philosophy has permeated into new efforts that provide a glimpse of how African cities could build post-pandemic.

Cape Town, South Africa

In Langa, the oldest township in Cape Town, a group of young men started a delivery business on their bicycles and recently a bicycle centre has sprung up seeking to encourage more people to use two wheels. The dire conditions of many townships, built on the urban peripheries during apartheid for ‘non-white’ residents and where the majority of the population lives, make such initiatives challenging. This video highlights the real challenges of unpaved roads – let alone bicycle lanes. Indeed, such efforts are a far cry from the many interventions European and some Latin American cities are implementing to promote the use of the bicycle, but it is certainly a start.

To-date, South African authorities have not promoted the use of NMT as a measure to prevent the spread of COVID-19, and temporary measures have not been instituted in a formal way. Nevertheless, there is consensus amongst mobility advocates that there might be a window of opportunity to push for the implementation of existing policies such as Cape Town’s Cycling Strategy. This window may also close as the lockdown eases and people return to their jobs and to what they consider ‘normal’.

Kampala, Uganda and Nairobi, Kenya

Both Nairobi and Kampala have completed major improvements to their NMT infrastructure during the pandemic. Kampala began to improve the walking and cycling facilities in sections of their central business district (CBD) in 2019, notably at the very busy Namirembe Road and Luwum Street area which is located near a major informal transport park. The completed projects were launched at the onset of the pandemic and have received a very positive response.

Nairobi, on the other hand, underwent governance changes earlier this year and the newly launched Nairobi Metropolitan Services commenced its work by improving the walking and cycling infrastructure within the CBD. They aim to extend this to adjacent neighbourhoods in line with the 2015 Nairobi NMT Policy that seems to have finally been put into effect. For these two cities, NMT infrastructure is critical, as their primary mode of transportation for more than 45% of their urban residents is walking.

Ethiopia

Across Ethiopia, the country’s recently launched NMT Strategy is taking big strides towards imagining and creating sustainable transport infrastructures that reflect the needs of the majority of users.

“In spite of the widespread use of non-motorised modes,” the strategy states, “transport planning and the provision of infrastructure in Ethiopian cities has been largely car-centred, underestimating the importance of NMT.”

The national and capital city NMT strategies seek to interrupt this, with a target of building nearly 430 km of pedestrian infrastructure and more than 300 km of cycling tracks across Ethiopia’s secondary cities, as well as 600 km of walkways and 200 km of cycling lanes in the capital, Addis Ababa, by the end of the decade. Ethiopia’s Open Streets movement –Menged Le Sew – complements this vision, by providing interactive community engagement and policy advocacy of what cities who put people first could become.

Looking forward

The pandemic is providing us a moment to reimagine everything, including how we move. With cities, especially in the Global South, marred by choking air pollution, never-ending vehicle fatalities and countless hours of lives lost sitting in traffic, Open Streets and pop-up NMT infrastructure are not only part of how we survive the pandemic – they are fundamental aspects of how we build just societies.

For these temporary mobility designs to remain more than a lockdown memory, their purpose must be shifted from pop-up to permanence to ensure we have streets that grant us clean air, safety and mobility for all.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Geographies in DepthSee all

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

April 25, 2024

Andrea Willige

April 23, 2024

Libby George

April 19, 2024

Apurv Chhavi

April 18, 2024

Efrem Garlando

April 16, 2024

Babajide Oluwase

April 15, 2024