Scientists have developed truly biodegradable plastics

A research team has found a way to make biodegradable plastics actually disappear, unlike ones that only claim to break down. Image: gricultural Research Service / Wikimedia Commons / CC0

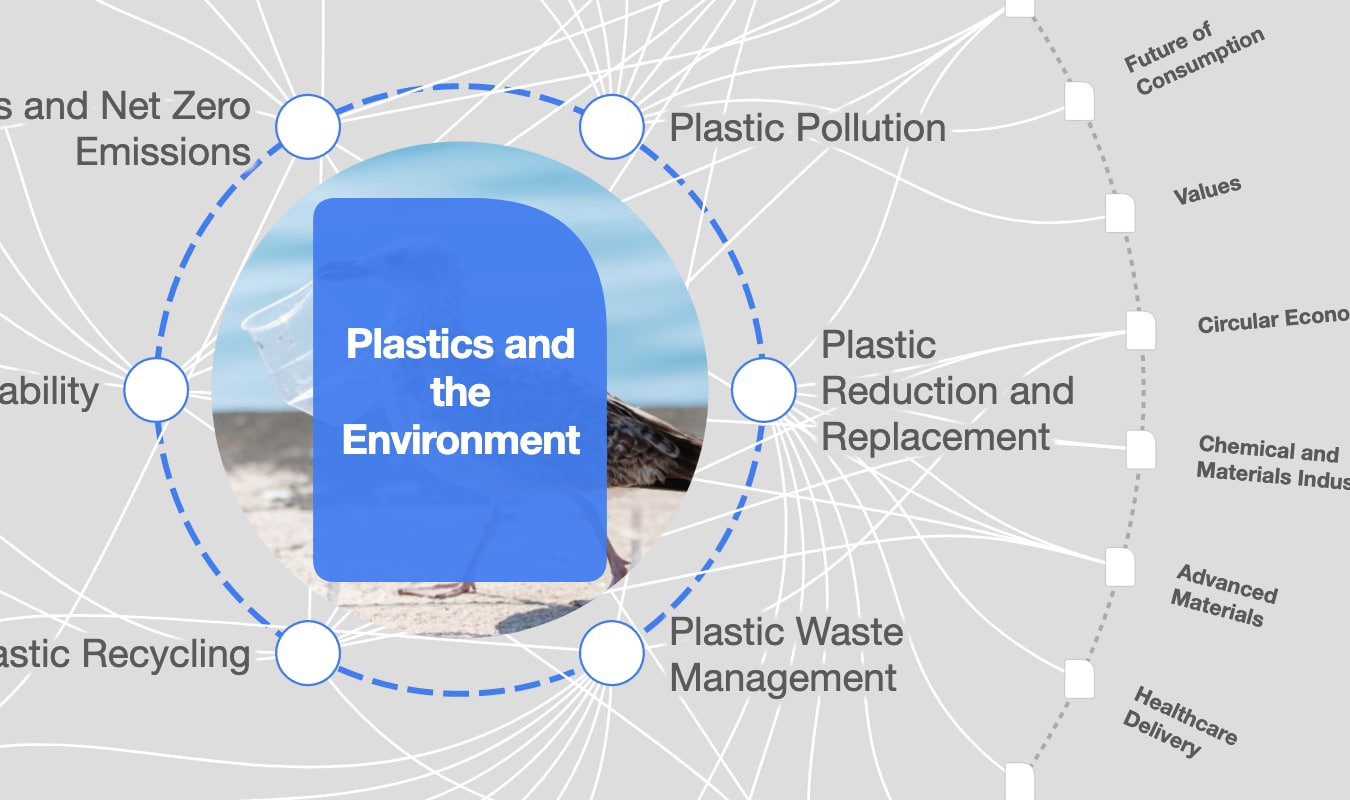

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Plastics and the Environment

- Typical plastics, even ones dubbed as biodegradable, may not biodegrade in certain environments.

- Since the 1950s, only 600 million metric tons of plastic have been recycled, compared to the 4.9 billion metric tons in landfill or polluting the planet.

- Researchers at the University of California have found a way to make plastics disappear, using plastic-eating enzymes.

A research team at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC), Berkeley has found a way to make biodegradable plastics actually disappear.

While biodegradable plastics have been touted as a solution to plastic pollution, in practice they don't work as advertised.

"Biodegradability does not equal compostability," Ting Xu, study coauthor and UC Berkeley polymer scientist, told Science News.

But by studying nature, Xu and her team have developed a process that actually breaks down biodegradable plastics with just heat and water in a period of weeks. The results, published in Nature on Wednesday, could be game-changing for the plastic pollution problem.

"We want this to be in every grocery store," Xu told Science News.

What's the problem?

Humans have tossed 6.3 billion metric tons of plastic since the 1950s and only recycled 600 million metric tons, leaving 4.9 billion metric tons sitting in landfills or otherwise polluting the environment, BBC Future reported. Plastic waste is a problem because it does not disintegrate, but only breaks apart into tinier pieces known as microplastics, which have infiltrated almost every part of the planet — and our bodies.

Biodegradable plastics were supposed to solve this problem, but face three main limitations, according to Berkeley News and Berkeley Lab.

- They get missorted and contaminate recyclable plastics.

- They end up in landfills, where the conditions are not suitable for plastic breakdown, so they last as long as forever plastics.

- When they are composted, they don't entirely degrade and still leave microplastics in the soil.

Xu told Science News that she had found supposedly biodegradable plastics in compost.

"It's worse than if you don't degrade them in the first place," Xu said.

The solution

To create plastics that do disappear, Xu and her team studied nature.

"In the wild, enzymes are what nature uses to break things down — and even when we die, enzymes cause our bodies to decompose naturally," Xu told Berkeley Lab. "So for this study, we asked ourselves, 'How can enzymes biodegrade plastic so it's part of nature?"

The researchers focused on a polyester called polylactic acid, or PLA, which is used for most compostable plastics. Berkeley News explains how the process works:

The new process involves embedding polyester-eating enzymes in the plastic as it's made. These enzymes are protected by a simple polymer wrapping that prevents the enzyme from untangling and becoming useless. When exposed to heat and water, the enzyme shrugs off its polymer shroud and starts chomping the plastic polymer into its building blocks — in the case of PLA, reducing it to lactic acid, which can feed the soil microbes in compost. The polymer wrapping also degrades.

What is the World Economic Forum doing about plastic pollution?

The researchers found that as much as 98 percent of their modified plastics converted into small molecules, leaving no microplastics behind. At room temperature, the plastics degraded by 80 percent after about a week. In the high heat of industrial composting conditions, plastics degraded even faster. They also disappeared after a few days in warm tap water.

What's next?

Aaron Hall, another study coauthor and a former UC Berkeley doctoral student, has founded a company to commercially develop these plastics.

Xu also thinks the process could apply to different types of polyester plastic and various recycling problems, such as developing compostable glue for electronics.

"It is good for millennials to think about this and start a conversation that will change the way we interface with Earth," Xu told Berkeley News. "Look at all the wasted stuff we throw away: clothing, shoes, electronics like cellphones and computers. We are taking things from the earth at a faster rate than we can return them. Don't go back to Earth to mine for these materials, but mine whatever you have, and then convert it to something else."

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

Dan Lambe

April 24, 2024

Roman Vakulchuk

April 24, 2024

Charlotte Kaiser

April 23, 2024

Jennifer Holmgren

April 23, 2024

Agustin Rosello, Anali Bustos, Fernando Morales de Rueda, Jennifer Hong and Paula Sarigumba

April 23, 2024

Carlos Correa

April 22, 2024