Microsoft’s new campus will run on geothermal energy - but what exactly is it and can it really help combat climate change?

Microsoft headquarters in Redmond, Washington. Image: Unsplash/Ricky Han

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

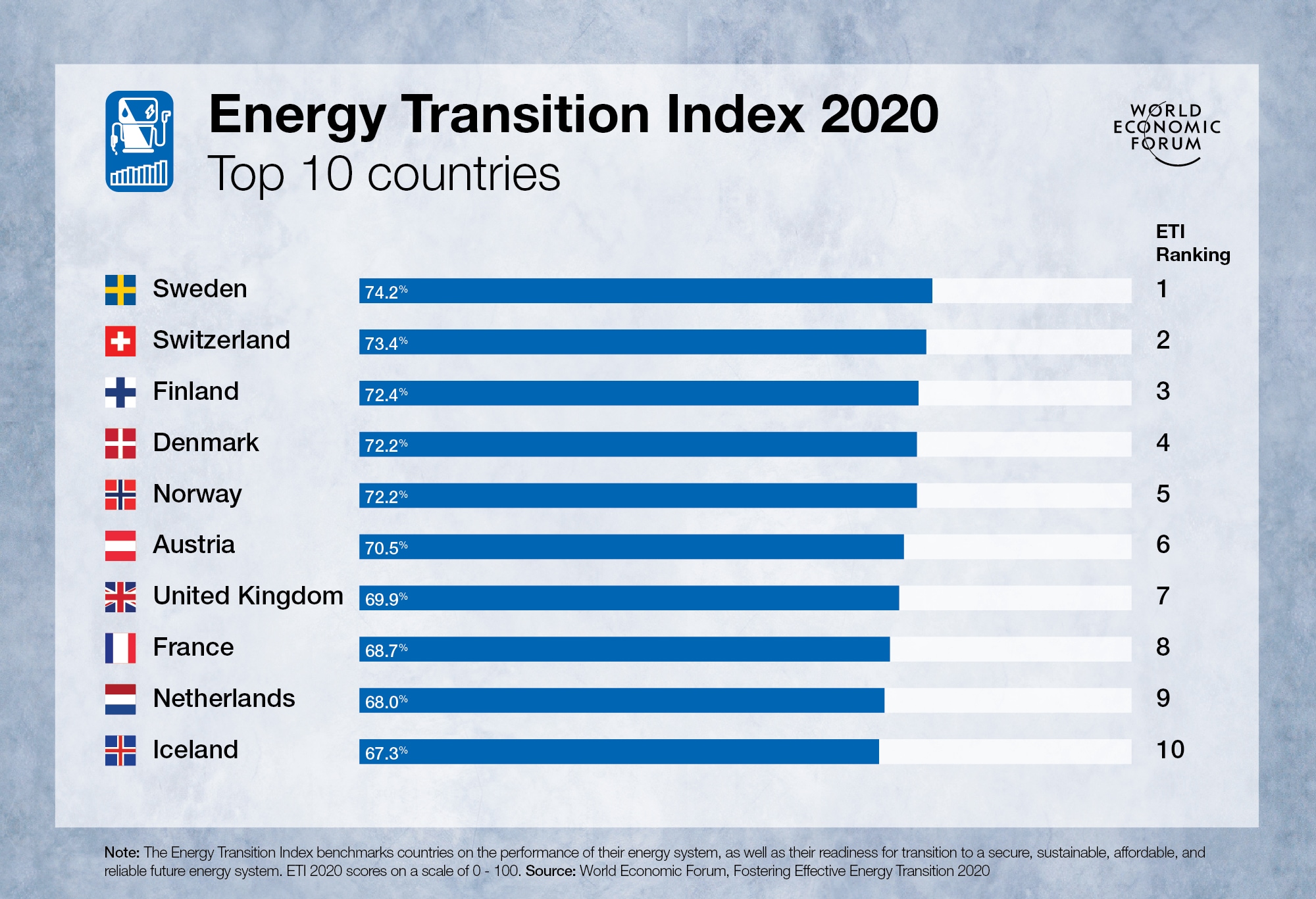

Energy Transition

- Microsoft is using the Earth’s geothermal energy to power its new sustainable campus in the US.

- This will reduce Microsoft’s energy use by more than 50%, the company says.

- Geothermal energy is natural heat stored below the surface that can be used for heating or cooling.

- This type of electricity generation could meet 25% of Europe’s energy needs by 2030.

- But geothermal energy generation needs to increase from 3% to 10% a year to meet sustainability goals.

Microsoft is using geothermal energy from deep underground to power its new sustainable campus in the United States.

The computing giant is building 93,000 square metres of new workspace on 29 hectares of its Redmond campus, east of Seattle in Washington state, as part of its pledge to be carbon negative by 2030.

“Our new Thermal Energy Center will generate heating and cooling for the campus using geowells that access and use the deep earth’s constant temperature,” Microsoft explains on its Building a modern campus page.

What is geothermal energy?

Geothermal energy is natural heat stored below the Earth’s surface that can be used for heating or cooling. It’s accessed via wells, dug deep underground.

Microsoft’s geothermal system will involve 875 geothermal wells drilled 167 metres into the ground across a 1 hectare field.

What's the World Economic Forum doing about the transition to clean energy?

The wells will comprise one of the biggest geothermal fields of its kind in the US to harness the Earth’s thermal energy, Microsoft says.

Water will be distributed across the campus in 354 kilometres of pipes to provide heating and cooling to the new sustainable office buildings, the first one of which is due to open in 2023.

Microsoft’s Thermal Energy Centre will be at the heart of this geothermal system. It will house “enormous chillers, cooling towers, back-up generators, solar panels” as well as 20 metre tanks that can store 1,270 cubic metres of water as thermal energy, according to Microsoft writer Vanessa Ho.

Microsoft says tapping into geothermal energy will reduce its energy consumption by more than 50%, compared to a typical utility plant.

Natural energy source

Geothermal energy is a rich source of renewable energy globally.

Iceland, for example, is a pioneer of geothermal energy and has an “abundant source of hot, easily accessible underground water,” says the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

This is provided by more than 200 volcanoes and many hot springs, which bring geothermal energy to the Earth’s surface through water or steam.

Iceland is helping Africa develop its geothermal resources through a UNEP project, the African Rift Geothermal Development Facility Project (ARGeo). East Africa could generate an estimated 20 gigawatts of electricity from geothermal energy, UNEP says.

Interest is growing in geothermal energy as an important alternative to wind and solar – which cannot generate enough electricity all the time to meet demand.

Meeting energy needs

The European Geothermal Energy Council (EGEC) describes geothermal energy as an “endless source of renewable energy, which can be used for heating, cooling, electricity and energy storage for countless uses in buildings, industry and agriculture”.

It could meet about 25% of Europe’s energy needs by 2030, EGEC says, and is one of the cheapest renewables in the long-term.

“After an initial installation investment, the operating costs are very low and predictable,” it adds.

But the world is currently not on track. Geothermal electricity generation rose by an estimated 3% in 2019, below the average growth of the five previous years, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

To meet the world’s global goals on sustainable development, it would need to increase 10% a year between 2019 and 2030, the IEA says.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Energy TransitionSee all

Liam Coleman

April 25, 2024

Tarek Sultan

April 24, 2024

Jennifer Holmgren

April 23, 2024

Ella Yutong Lin and Kate Whiting

April 23, 2024

Nick Pickens and Julian Kettle

April 22, 2024