Could blockchain help track outbreaks like e. coli in spinach?

Blockchain can be used to capture data along the food supply chain. Image: Unsplash/GuerrillaBuzz Crypto PR

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Blockchain

- Retailers such as Walmart have been promoting blockchain as a way of tracing perishable foods as they travel through the supply chain.

- Blockchain’s ability to capture data along the supply chain makes it a fast and efficient way to pinpoint where contamination or other safety issues may have originated.

- However, new research suggests there are concerns around how the technology could be used to maximize profitability at the expense of farmers, leading to more supply chain problems.

Food contamination outbreaks are regular occurrences in the United States food system and can be costly. In 2006, for example, 276 consumer illnesses and three deaths were attributed to an E. coli outbreak in California, during which spinach disappeared from supermarket shelves nationwide for two weeks and the state’s farmers incurred losses of $74 million.

To protect themselves and their customers, retailers such as Walmart have been promoting blockchain as a novel method for tracing perishable foods such as leafy greens as they travel through the supply chain.

But what is the impact of such traceability technology, particularly on the strategic behaviors of stakeholders within the supply chain, and does it make good on its promises to increase safety and reduce waste? The answer, Fasheng Xu, professor of supply chain, operations, and technology at Syracuse University and his colleagues found in their theoretical model, is complex and depends on the configuration of the supply chain.

The greatest benefit of blockchain in this context is immediately apparent: Its ability to capture, maintain, and grant access to data along the supply chain makes it fast and efficient to pinpoint where contaminated spinach or other produce came from, allowing the continued sale of unaffected products. (The researchers call this the “pure traceability effect.”)

Considering the different stakeholders within the supply chain—retailers, suppliers, and farmers—complicates the picture. “They’re self-interested, and playing games with one another to try and maximize their profit,” Xu explains. “Their strategic actions may backfire and may not lead to win-win-win but to a triple loss.” (This is termed the “strategic-pricing effect.”)

For example, Walmart may strategically reduce the wholesale price for spinach, leading distributors to offer a lower procurement price to farmers. “The direct result is that the farmers are going to put less effort into improving supply chain safety, so as a result contamination risks will become higher after this technology adoption,” Xu says. The system and its individual supply chain members, including the retailer, end up worse off.

Having a greater number of farmers in the system, however, eventually allows the benefits of pure traceability to surpass the strategic-pricing effect. “When we have so many farmers, it becomes more valuable to quickly identify which farm the contamination was coming from, because otherwise we need to destroy the produce from all the farmers,” Xu explains.

In practice, the researchers recommend managers lock in the pricing system when traceability technology is put in place to discourage supply chain members from using strategic pricing and ensure that the benefits of the new system are distributed equally. “Walmart can make a commitment to the upstream suppliers saying that after they’ve adopted this technology, it’s not going to change the wholesale price,” Xu says.

In fact, perfect traceability may not even be the best solution. “There are many different ways to offer alternative risk mitigation measures, such as safety inspections in the middle of the supply chain,” Xu says. The study’s model, however, only applies to this specific case of perishable produce, he makes sure to emphasize. “If you look into other types of supply chains, like vehicle parts, it’s a different story.”

Coauthors of the study are from the John M. Olin School of Business at Washington University in St. Louis. A paper on the findings is forthcoming in the journal Management Science.

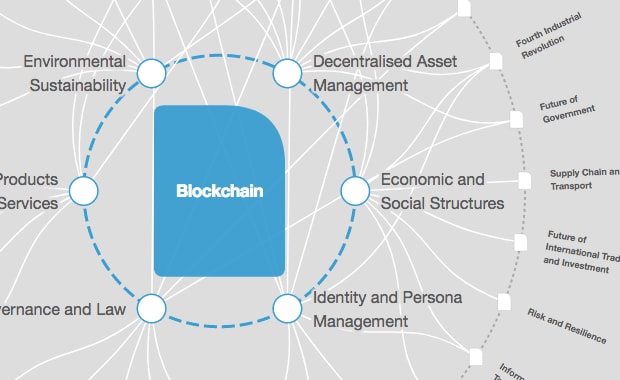

What is the World Economic Forum doing about blockchain in supply chains?

Have you read?

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Emerging TechnologiesSee all

Thomas Beckley and Ross Genovese

April 25, 2024

Robin Pomeroy

April 25, 2024

Beena Ammanath

April 25, 2024

Muath Alduhishy

April 25, 2024

Vincenzo Ventricelli

April 25, 2024

Agustina Callegari and Daniel Dobrygowski

April 24, 2024