How do you measure the thickness of sea ice?

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

Yale University scientists have answered a 40-year-old question about Arctic ice thickness by treating the ice floes of the frozen seas like colliding molecules in a fluid or gas.

Although today’s highly precise satellites do a fine job of measuring the area of sea ice, measuring the volume has always been a tricky business. The volume is reflected through the distribution of sea ice thickness — which is subject to a number of complex processes, such as growth, melting, ridging, rafting, and the formation of open water.

For decades, scientists have been guided by a 1975 theory (by Thorndike et al.) that could not be completely tested, due to the unwieldy nature of sea ice thickness distribution. The theory relied upon a term that could not be related to the others, which represented the mechanical redistribution of ice thickness. As a result, the complete theory could not be mathematically tested.

Enter Yale professor John Wettlaufer, inspired by the staff and students at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Summer Study Program at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, in Massachusetts. Over the course of the summer, Wettlaufer and Yale graduate student Srikanth Toppaladoddi developed and articulated a new way of thinking about the space-time evolution of sea ice thickness.

The resulting paper appears in the Sept. 17 edition of the journal Physical Review Letters.

“The Arctic is a bellwether of the global climate, which is our focus. What we have done in our paper is to translate concepts used in the microscopic world into terms appropriate to this problem essential to climate,” said Wettlaufer, who is the A.M. Bateman Professor of Geophysics, Mathematics and Physics at Yale.

Wettlaufer and co-author Toppaladoddi recast the old theory into an equation similar to a Fokker-Planck equation, a partial differential equation used in statistical mechanics to predict the probability of finding microscopic particles in a given position under the influence of random forces. By doing this, the equation could capture the dynamic and thermodynamic forces at work within polar sea ice.

“We transformed the intransigent term into something tractable and — poof — solved it,” Wettlaufer said.

The researchers said their equation opens up the study of this aspect of climate science to a variety of methods normally used in nonequilibrium statistical mechanics.

This article is published in collaboration with Yale. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Jim Shelton is the Senior Communications Officer for Science & Medicine at Yale University.

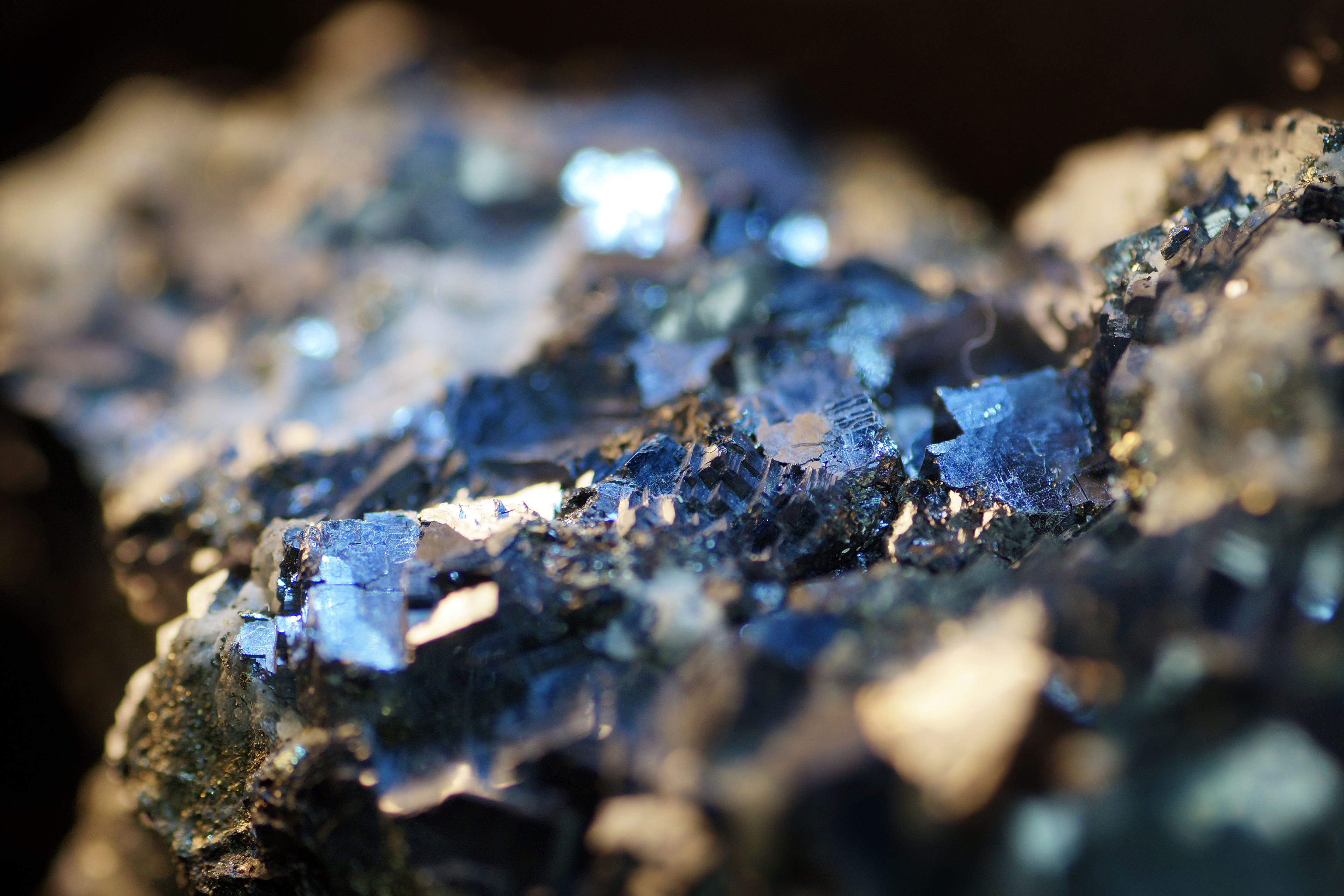

Image: Adelie penguins walk on the ice. REUTERS/Pauline Askin/Files.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

Andrea Mechelli

May 15, 2024

Sha Song

May 8, 2024