Four Nobel economists on the biggest challenges for 2016

How to manage risk, sluggish productivity, deteriorating patterns of growth, relocating refugees – what keeps economists up at night? Image: REUTERS/Toru Hanai

A. Michael Spence

Philip H Knight Professor Emeritus and Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford Graduate School of Business

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Fourth Industrial Revolution

What are the biggest economic challenges facing the world in 2016? We put this question to four winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, all of whom will be attending this year's Annual Meeting in Davos. Here's what they had to say.

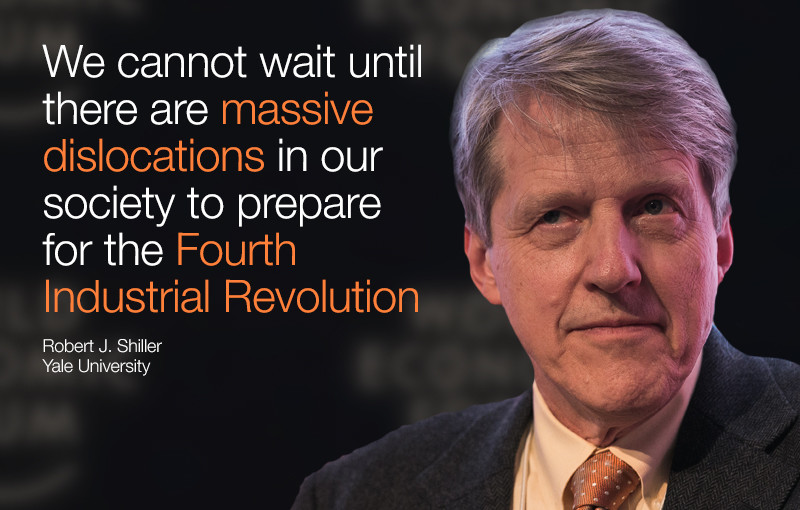

Robert J. Shiller, Sterling Professor of Economics, Yale University, USA. Awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize for Economic Sciences in 2013.

The theme of this year's World Economic Forum's Annual Meeting in Davos is "Mastering the Fourth Industrial Revolution". This revolution has been designated as one of "cyber-physical systems," or, roughly speaking, advanced robots, driverless cars, the Internet of Things, and the like.

I commend the Forum for choosing this theme, for it is indeed the biggest issue facing the world today.

It does seem that such a revolution is coming, someday, but it also seems presumptive that democratic society can "master" it. Such a revolution portends great changes in economic status for individuals and changes in the political power of various groups in society.

I would prefer that we make as an objective that we do what we can to "risk manage" it. By this I mean that we set in place a plan today to deal with the possible dislocations caused by this revolution. We do not know yet who will benefit and who will suffer from the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In a sense, it is good that we do not yet know, for this means that we can use the tools of risk management to manage it. You cannot wait until a house burns down to buy fire insurance on it. We cannot wait until there are massive dislocations in our society to prepare for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

One concrete proposal that I have made, in my 2012 book, Finance and the Good Society and elsewhere, is that we should legislate now a long-term tax and benefits plan to deal with a possible huge increase in economic inequality, should the Fourth Industrial Revolution lead to this. If the revolution turns out to be benign, then we will have lost virtually nothing. Should the revolution turn out not to be benign, we will be glad we did this.

One way to view this is as using modern financial principles to manage risk. Another way to view it is as developing a moral consensus now, from the Rawlsian original position, on what should be done if this revolution has unpleasant consequences.

Professor Edmund S. Phelps, The Center on Capitalism and Society, Columbia University, USA. Awarded in 2006.

The “modern project” to innovate began in Britain and America around 1820, then reached Germany and France around 1880. Their dynamic economies provided rising productivity and expanding trade around the world. The passion to participate, the fascination with the unknown, and the “rage for the new” set an example to the world of what working lives could be. The way was clear for men and women to prosper and to flourish. Yet, despite the digital and internet revolutions, aggregate innovation wound down in the mid-1900s. Total factor productivity, which grew at better than 2% a year for decades, has grown at 1% after the ‘60s.

Nothing has been the same since. With productivity slower, capital goods output fell to a lower growth path and the male labour force fell in parallel. Tax revenues slowed alongside productivity while politicians, deploring “austerity,” plan on permanent fiscal deficits – as if they were sustainable in a near-zero growth economy. Thus the West has been in a crisis. The Asian and Latin American nations need all the more to find their own dynamism.

The difficulty is that standard economics – both neo-classical, Keynesian and supply-side economics – is unsuited to find the cure. The economy is not a machine that can be cranked up to the best possible performance level: a functioning modern economy is a living organism made up of all the individuals participating in it. Their initiatives are sparked by imagination, encouraged by values and assisted by their personal knowledge.

A. Michael Spence, William R. Berkley Professor in Economics and Business, NYU Stern School of Business, Italy. Awarded in 2001.

One of the biggest economic challenges for 2016 is to reverse the deteriorating pattern of global growth. All kinds of trouble awaits if the present trend continues. Fiscal distress, persistent unemployment, rising inequality, and the loss of political and social cohesion to name just a few.

A key element is beginning to deal with the shortage of aggregate demand that is constraining the growth, trade, inflation, and exacerbating fiscal distress. The combination of low growth and inflation below target (also in part a product of the aggregate demand problem) significantly increases the difficulty of reducing excess sovereign indebtedness without deflates or the equivalent. That in turn constrains counter cyclical space and public sector investment, which contributes to lower aggregate demand and reduces future growth via the negative impact on private sector investment returns.

Other measures to increase private investment would help. They vary from country to country. Reforms targeted at reducing structural rigidities in a number of advanced and developing countries are needed. Tax reform in the US and a more serious addressing of deteriorating income distributions would also help. Avoiding competitive currency devaluations on the negative side is important, as it does not solve the global growth issue. Unblocking intermediation channels between large pools of savings and public and urban investment needs would measurably improve overall economic performance.

This multi-dimension growth challenge cannot be met in a single year, or even 3-4 years. But it should be a central focus of the G20 economic agenda in China. The challenge is not made easier by the fact that major structural changes and adjustments of a secular nature caused primarily by digital technologies are ongoing and may accelerate in middle and high income countries.

Monetary policy has done what it can do. It needs to be complimented by a host of complementary growth-oriented measures, none of which are part of the monetary policy toolkit, measures that thus far have been notably absent. Staying on the present course will leave the global economy largely unarmed with respect to future shocks. And long term repression of the returns on savings has its own very substantial costs.

Alvin Roth, Professor, Department of Economics, Stanford University, USA. Awarded in 2012.

One important challenge for 2016 and beyond will be thinking about refugee (and other migrant) resettlement.

Refugee relocation is a matching problem, in the sense that how a refugee thrives can depend on which country they go to. Determining who should go where, and not just how many go to each country, should be a major goal of relocation policy.

This will be important not just because we want refugees and other migrants to do well, but because it’s hard to keep them where they don’t want to be. In the U.S., where immigrants may relocate at will once they have entered the country, this is especially clear. So the information and preferences of the refugees themselves about where they could thrive shouldn’t be ignored.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Fourth Industrial RevolutionSee all

Thomas Beckley and Ross Genovese

April 25, 2024

Agustina Callegari and Daniel Dobrygowski

April 24, 2024

Christian Klein

April 24, 2024

Sebastian Buckup

April 19, 2024

Claude Dyer and Vidhi Bhatia

April 18, 2024