Why cities hold the key to safe, orderly migration

Toronto, Barcelona and New York have offered themselves up as sanctuary cities. Many others must follow suit. Image: Reuters/Mark Blinch

Harald Bauder

Professor of Geography and the Director of the Graduate Program in Immigration and Settlement Studies, Ryerson University, TorontoLoren Landau

South African Research Chair for Mobility & the Politics of Difference, African Centre for Migration & Society, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Migration

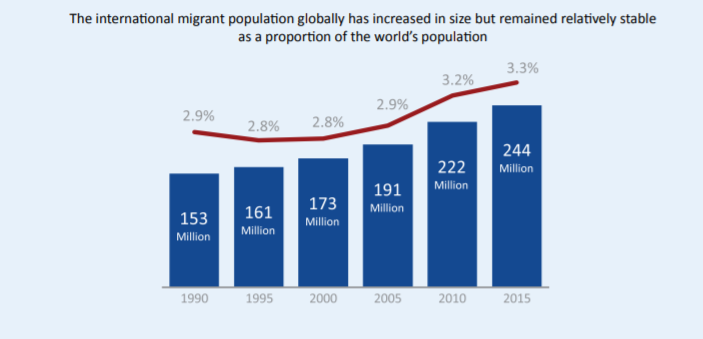

Migration is largely an urban phenomenon. According to the 2018 World Migration Report, “nearly all migrants, whether international or internal, are destined for cities”.

Cities respond very differently to migration. Many cities are supportive, boost the rights of migrants and reap the benefits of migration. The mayors of these municipalities are frequent panelists and speakers, extolling the virtues of migration, and proudly proclaiming that the future of migration is local. Other cities, however, seek to restrict migration and actively exclude migrants from social, economic and political participation.

This dual role poses a challenge to the implementation of the United Nations’ ambitious agenda, presented in the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. The Global Compact for Migration, as it’s also known, is an intergovernmental agreement on multiple dimensions of international migration; this agreement is expected to be adopted by the vast majority of UN member states in December 2018.

In support of migration, the mayors of major migrant destination cities, such as New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, are standing up against national policies that treat migrants unfairly and deny them rights and services. In January of 2017, New York’s Mayor Bill de Blasio proclaimed that “we’re going to defend our people regardless of where they come from, regardless of their immigration status”. With this proclamation, De Blasio reaffirmed New York’s status as a sanctuary city that protects the city’s most vulnerable inhabitants.

Cities in other countries pursue a similar approach. In 2013, the Canadian city of Toronto declared itself a sanctuary city, inspiring other Canadian cities to follow suit. Cities like Barcelona in Spain or Quilicura in Chile pursue a similar approach, although they don’t call themselves sanctuary cities but a “Refuge City” and “Commune of Reception” respectively.

Although African cities have been notably missing in many of the global debates on refugee support or migrant integration, they too are stepping tentatively on to the stage. Although often constrained by highly centralised financial and political authorities, they are exploring options for building services that can accommodate mobility in all its forms. Arua in northern Uganda, for example, has embraced its role as a destination for migrants and refugees from South Sudan. The Cities Alliance is now working with “secondary cities” across Asia, Africa and Latin America to find ways to incentivize similar responses.

These cities are assuming responsibility in addressing and reducing the vulnerabilities in migration, which is one of the key goals of the Global Compact for Migration. They commit to providing basic services for migrants, and seek to ensure that migrants receive access to these services free of discrimination, based on race, gender, religion, national or social origin, disability or migrant status.

However, cities can also play a darker role in the migration process. As a set of institutions closely connected to a local political constituency, cities are often more responsive to popular attitudes than more distant national administrations are. Where there are strong pro-migrant business, religious or civic bodies, cities may embrace mobility. But this is not always the case. Indeed, some migrant-receiving cities are enacting restrictive local policies in an effort to repel newcomers and drive out migrants already living within their municipal borders. In 2006, the Pennsylvania town of Hazelton pioneered – albeit ultimately unsuccessfully – this type of local policy by making it more difficult for irregular migrants to rent housing or get employment in the municipality. In Canada, the Quebec town of Hérouxville took a swipe at Muslim migrants by introducing a “code of conduct” in 2007 that, among other measures, prohibited the stoning of women. Other cities simply passively comply with or support national immigration raids and exclusions.

African cities are not immune to creating hostile environments for migrants. The mayor of Johannesburg, Herman Mashaba, has been accused of anti-migrant tactics and announced earlier this year that he will actively cooperate with national authorities in conducting immigration raids. In Nairobi, authorities have cooperated with national police in rounding up Somali refugees, even while turning a blind eye to a range of other international migrants living in the city. Other municipal or sub-municipal authorities across Africa have also actively and sometimes violently moved to exclude outsiders. Sometimes these are refugees and international migrants. Sometimes they are migrants from within their own countries.

These cities are, in fact, increasing the risks and vulnerabilities migrants face, counteracting the intentions of the Global Compact for Migration.

Cities around the world encounter diverse situations as migrant destinations, transit hubs or places of departure; they have different histories and find themselves in different geopolitical situations; some cities are richer and others are poorer; and cities in different countries possess different levels of autonomy from national and regional governments.

What is clear, however, is that the successfully implementation of the Global Compact for Migration requires the cooperation of cities.

Cities that lack a strong local pro-migration constituency will require incentives to be inclusive of migrants. Such incentives might involve financial support and access to resources and programmes from national and international bodies. Enhancing local authority and participation can ironically make it more difficult for local authorities to fight for unpopular refugees and migrants. Global norm-setting can help counter such moves, but advocates and authorities also need to operate more quietly, stealthily incorporating refugees and migrants into their programmes across sectors. Indeed, migration policy per se is likely to offer few protections if local policies for housing, employment, education, commerce, trade and planning do not consider mobility.

As recent as 2015, William Lacy Swing, the director-general of the International Organization of Migration (IOM), lamented at the Conference on Migrants and Cities that “city and local government authorities have so far not had a prominent voice in the global debates on human mobility”. This situation is changing. Cities increasingly assert their voices and are recognizing that they are key partners in tackling the challenges of migration.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Urban TransformationSee all

Lisa Chamberlain

April 25, 2024

Victoria Masterson

April 17, 2024

Fatemeh Aminpour, Ilan Katz and Jennifer Skattebol

April 15, 2024

Victoria Masterson

April 12, 2024