You can now live for ever. (Your AI-powered twin, that is)

A growing number of companies are exploring how AI can be used to create digital models of people's personalities. Image: Christopher Burns/Unsplash

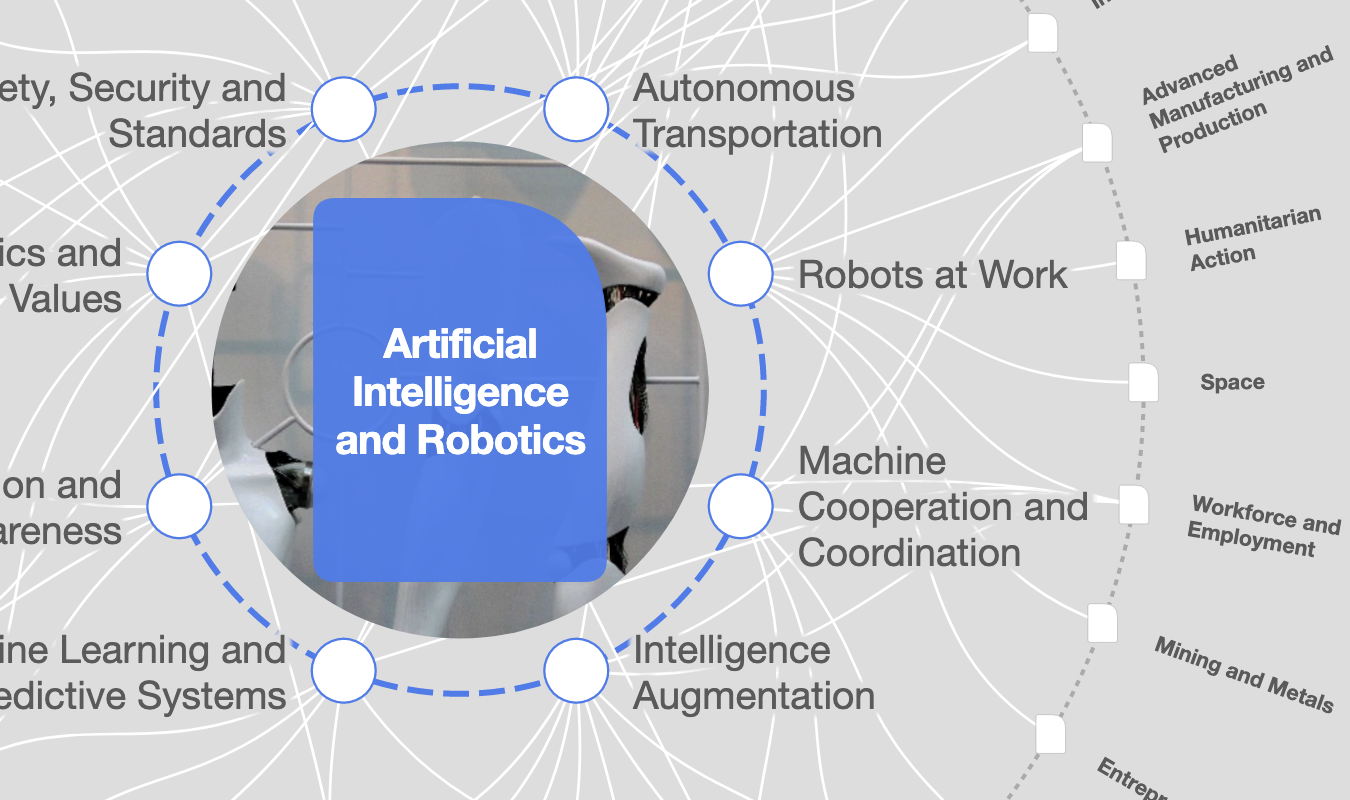

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Emerging Technologies

- A growing number of companies are exploring how AI can be used to create digital models of people's personalities.

- Mind Bank Ai is a startup that enables customers to create a "digital twin" of themselves that could eventually talk and think like the real person.

- After someone dies, their digital twin could provide comfort to surviving loved ones, says the company, if it doesn't upset the grieving process.

Mind Bank Ai is the newest entrant in an ambitious idea: using AI to create a kind of immortality.

It’s January 17, 2020 — the world has yet to change; Wuhan locks down six days later — and Emil Jimenez is on a train from Vienna to Prague. His daughter, then four years old, inadvertently activates Siri while playing pony games on her iPad.

“She’s like, ‘Daddy,’ y’know, ‘what is this?’” Jimenez tells me on a video call from the Czech Republic. Jimenez tells her it’s Siri, and encourages her to talk to the digital assistant.

Her first question is if Siri has a mother.

From there, she peppers the artificial intelligence with the kinds of questions kids ask — do you like ice cream? do you like toys? — and, by the end of their conversation, tells Siri she loves it, that she’s her best friend.

Jimenez, who has a background in psychology, sees this heartwarming interaction and is struck by how quickly and seamlessly his daughter formed a relationship with the AI — we usually ring Siri when we need something, even if it’s a laugh.

But a generation reared on conversational interactions with technology is quickly developing a relationship with devices, AIs, and robots completely different from those of us who didn’t come of age with AI, Jimenez thinks.

Jimenez knows how Siri works — how a natural language processing algorithm understands your speech, how a deep-learning black box sits up in a cloud, from which Siri throws down answers like a baby Zeus.

How is the World Economic Forum ensuring the responsible use of technology?

And he has an idea.

“Today (my daughter) speaks to Siri. But one day in the future, I want her to speak to me. Because I know I’m not going to be around forever, and I love my daughter to bits …

“What if I’m always able to help her?”

A personal digital twin

This is a story about “your” future. Or at least, your possible future.

Jimenez’s desire led him to found Mind Bank Ai, a startup whose mission is staggeringly ambitious: to break the chain of death and knowledge loss — at least, for those you leave behind.

The company wants to provide a simulacra of you that can live indefinitely — can be called upon, consulted, commiserated and joked and argued with.

This “personal digital twin” Mind Bank Ai envisions will be built up, across your lifetime, from a data set of you.

Through conversations — a mixture of prompted topics and more organic interaction — the AI will craft a model meant to “think” like you, understand your personality, and, eventually, be able to apply that model to future conditions: answering as you would, conversing like you would.

“What’s wrong? What do you like to eat? How did you meet your wife? Why are you divorced?” Jimenez laughs. He envisions Mind Bank Ai asking “all the questions of life,” akin to the conversations we have to get to know one another. (Getting to know us is, essentially, what the AI would be doing, after all.)

Jimenez wants to create a digital twin which would, at the least, speak in your voice, as voice can be powerfully evocative, capable of bringing how you look (however they want you to look; healthy if you had been sick, for example) in their mind’s eye.

While that personal data is gathered, users can take these conversations with Mind Bank Ai as a chance to self-reflect and better get to know themselves — Socratic psychology, or “a fitness tracker for your mind” — Jimenez says.

Jimenez envisions interacting with Mind Bank Ai as a chance to self-reflect, while all the while the digital twin becomes closer to being like you.

Speaking forever

It is after you die that Mind Bank Ai would truly come into its own, like a digital cryogenics lab.

A personal digital twin is the latest iteration of an idea as old as humankind: the desire to, if not live forever, then at least be able to pass on your knowledge, experience, insights.

While your perfect digital twin will not be winking into life anytime soon, the capabilities of modern natural language processors (the deep-learning programs behind Siri, Alexa, and predictive texting) and the impressive facsimiles known as deepfakes are moving the idea from the fantastical to the might-be-possible.

Some computer programmers and startups already have creations similar to Jimenez’s vision.

Replika founder Eugenia Kuyda created a digital version of her dear friend, Roman Mazurenko.

“As she grieved, Kuyda found herself rereading the endless text messages her friend had sent her over the years — thousands of them, from the mundane to the hilarious,” The Verge‘s Casey Newton wrote. With Mazurenko relatively inactive on social media and his body cremated, his texts and photos were all that was left.

Kuyda, up until that point, had been working on the Y Combinator-backed Luka, a messenger app for communicating with bots. Using Mazurenko’s personal canon, she created a bot that could respond like her friend when prompted.

“She had struggled with whether she was doing the right thing by bringing him back this way,” Newton reported. “At times it had even given her nightmares.”

Those deep schisms had spread to their extended friend group, as well; some refused to interact with the Roman bot, while others found relief from it.

And then there’s the Dadbot, created by James Vlahos. When his father was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, Vlahos recorded everything he could to create Dadbot — a form, as Vlahos described it in WIRED, of “artificial immortality.”

Vlahos is now the CEO of HereAfter AI, which designs “legacy avatars” built from recorded interviews.

“They are this digital agent that’s modeled after the person who created it,” Vlahos says. “It shares primarily their life story and memories, and secondarily, their persona, their personality; the way they talk, their jokes, their wisdom, that type of thing.”

You can interact with a legacy avatar just like Siri or Alexa, except it will answer personal questions — in the person’s own voice.

The kind of digital twin Mind Bank Ai wants to create, however, is a step beyond this, and presents a wealth of opportunities and challenges, both technical and philosophical.

How far are we from creating a you that feels real? What decisions could we trust them with? Will they help us grieve, or cause us never to let go?

The architecture of a mind

Sascha Griffiths is the person tasked with building the bones and brain of your digital twin.

The co-founder and chief technology officer of Mind Bank Ai, Griffiths is currently researching and coding, pulling together the AI algorithms and tools they believe will be needed to copy you.

An array of AIs may come into play: topic modeling (which mines abstract “concepts” in language); sentiment analysis (basically, feelings recognition); and generative adversarial networks (the technology behind deepfakes) could all be conscripted.

As the project evolves, Griffiths aims to develop more bespoke algorithms to craft a better digital twin.

But few will be as important, especially in the early days, as natural language processing (NLP).

NLPs are most commonly used in digital assistants and predictive texting; GPT-3, which recently made a splash in AI circles, is an NLP that pulls from the mighty corpus of the internet to craft realistic text, from conversations to essays.

There will be a fundamental difference between those NLPs and your digital twin, says Ahmet Gyger, an AI researcher and advisor to Mind Bank Ai. Those current relationships are transactional; you give the NLP a command or question, and it finds you an answer.

“Whereas this one is more building over time,” Gyger, who was formerly a lead engineering program manager for Siri, says. Mind Bank Ai could help users understand how they feel in relation to past events and possibly build “an overt understanding about somebody’s life experience.

“And once you get that, then you open the door to being able to say ‘well, how will that person react in a new situation?’ And that becomes really interesting.”

By digesting the underlying patterns in how you talk, text, and write, an NLP can recreate a decent version of you fairly easily, says Griffiths — so long as it’s a line-by-line, question/answer type of conversation.

But to have a true conversation, he believes, is not yet possible. The “legacy avatar” of HereAfter AI can be created today, but Mind Bank Ai’s digital twin is still in the distance — HereAfter AI avoids open-ended conversation, which Vlahos calls a “nightmare.”

“Even if we could capture and interpret all linguistic and non-linguistic cues, another big problem would be to generate novel things for the ‘digital twin’ to say,” Christos Christodoulopoulos, a senior applied scientist on the Amazon Alexa team, not associated with Mind Bank Ai, tells me via email.

Many of the things we do in daily life are “scripted,” to a degree. When it comes to these kinds of interactions, AI is already capable of imitating us: ordering a coffee is pretty close to a script, but “our crucial, meaningful interactions aren’t,” Christodoulopoulos writes.

“Think of trying to comfort a friend after a break-up, or share in your spouse’s joy when they get a promotion: if you relied on formulaic, ‘canned’ responses, it would sound hollow — no better than interacting with a stranger.”

Common sense

Among the challenges Mind Bank Ai will need to overcome is understanding people’s emotions, cultures, and backgrounds. And to deliver an AI that is nimble and capable of handling a wide array of interactions, it will also need to overcome the brittleness inherent in AIs.

AI is “brittle” because it cannot operate outside of what it knows. When it encounters an input it can’t recognize, it will fail — often spectacularly.

Vered Shwartz, a postdoc researcher at the Allen Institute for AI and the University of Washington’s Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, offers an example.

When researchers tested GPT-3, they told the AI about a scenario where a cat was waiting by a hole for a mouse to emerge. Tired of waiting, the cat got too hungry. When they asked GPT-3 what the cat would do, it replied that it would go to the market and buy some food.

Clever, but wrong.

“The kind of mistakes that it makes is not even human-like,” Shwartz says. “It’s often the lack of common sense, the things that every adult human knows, and these models, they just don’t really know them.”

There are currently two main approaches to tackling the problem, Shwartz says. One is to gather all common knowledge so that AI can be trained on it — no trivial matter. Gathering the vast amount of data needed is taking decades.

“It’s impossible to collect everything,” Shwartz says, never mind how expensive that would be. And knowledge in text suffers from “reporting bias,” where the unusual is overrepresented, because that’s what’s worth writing down.

The Data Is You — The Twin Is Not

Whereas a GPT-3 learns via scouring everyone on the internet, your digital twin will be concerned with only one, comparatively narrow, data set: you.

There’s of course privacy concerns, but where the real tricky ethics comes in is when the data ceases to be you and is transformed into your digital twin.

A Mind Bank Ai digital twin would not be you, Griffiths says, but a representation of you. It would be trained on your data; it would (they hope) sound, speak, and “think” like you.

But it would not be an uploaded brain or a continuation of your existence. It won’t grow, evolve, change, or learn like you would.

So could we trust a digital twin of your spouse to weigh in on your end of life decisions? A digital twin of a company’s founder troubleshooting problems seems pretty acceptable, but just how much sway should a voice, not just from beyond the grave but beyond humanity itself, carry? Can you will it to have a board seat and voting rights?

There’s thornier issues, too. AI is far better at pattern recognition than human beings, and the NLP could find patterns in your speech and “thought” that you were not aware of. Applying these could make for an even more accurate digital twin, one which, in a narrow way, knows you better than you know yourself.

But if the digital twin’s AI seizes on some particular pattern, it could potentially craft a version of you which is amplified or distorted.

“One piece of data could tweak it in these really bizarre ways,” philosopher Susan Schneider, founding director of the Center for the Future Mind at Florida Atlantic University, says. “Leaving a loved one confused; ‘would grandpa do this?’”

The algorithms powering the digital twin would likely still be susceptible to brittleness, potentially causing catastrophic cat-goes-to-the-supermarket type of failures.

The danger is that AI’s ability to make plausible, convincing arguments may outstrip its grip on common sense. If we catch the failure, we may become distrustful and alienated from our digital friends, rather than being comforted — and if we don’t, we risk being misled.

Schneider fears the process of grieving could be upended, as well. Could a digital twin be so convincing that we never truly move on?

To Jimenez, the answer could be yes. But the opposite could be true, too.

Faced with grief, people traditionally turn to religion, Jimenez says, seeking a response to their searing questions that may never come.

However, what if they could also consult a digital twin? The digital twin of your spouse could tell you it’s time to find someone new, or encourage you to get back into that one passion you used to care so much about.

“How nice would it be if you actually got some answers?” Jimenez asks.

“That’s the hope at least, right?”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Emerging TechnologiesSee all

James Fell

April 26, 2024

Alok Medikepura Anil and Uwaidh Al Harethi

April 26, 2024

Thomas Beckley and Ross Genovese

April 25, 2024

Robin Pomeroy

April 25, 2024

Beena Ammanath

April 25, 2024

Vincenzo Ventricelli

April 25, 2024