What is the future of biochar as a climate change mitigation tool?

Biochar production can help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture and tackle climate change. Image: Flickr

Adele Peters

Staff Writer, Fast Company

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Biotechnology

- Biochar is a charcoal-like material made from organic waste.

- It can be used to store carbon for hundreds or thousands of years.

- Biochar is a relatively inexpensive and scalable way to remove carbon from the atmosphere.

- It can also be used to improve soil health and reduce the need for fertilizer.

On a site next to a sawmill in Waverly, Virginia, a startup takes sawdust and offcuts from the mill and heats it up to turn it into biochar, a material that can store carbon for hundreds or thousands of years. The project, which recently began operating, will capture a little more than 10,000 metric tons of CO2 each year. Microsoft will buy the carbon removal credits as part of its plan to become a carbon negative company.

It’s one of a growing number of biochar production plants. The potential is big: A new study calculated that if biochar production scales up as much as possible globally, it could capture as much as 3 billion metric tons of CO2 a year, or 6% of global emissions. Here’s how it works.

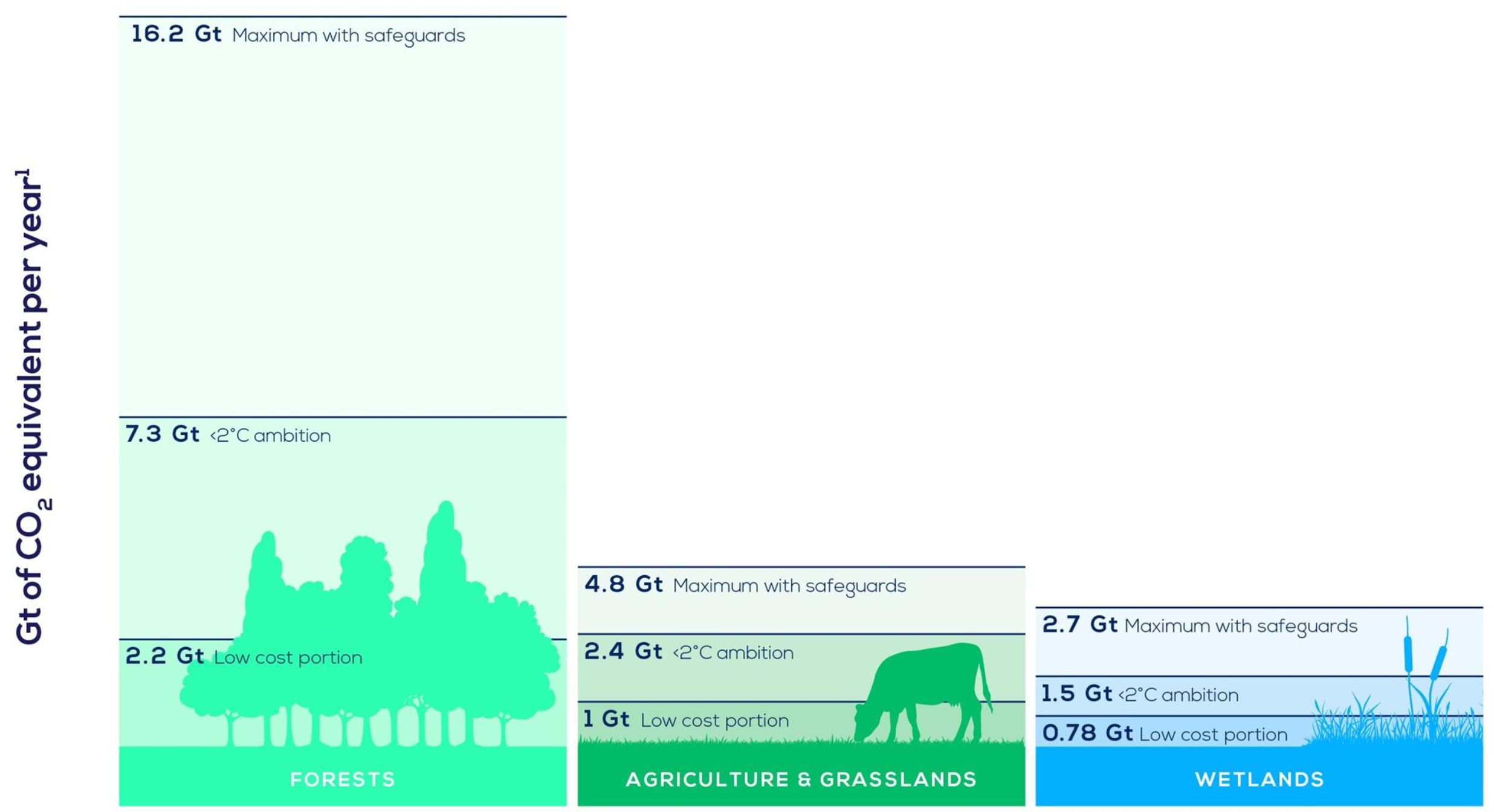

What is the World Economic Forum doing on natural climate solutions?

What is biochar?

When organic waste (like wheat stalks or manure from a farm, or sawdust from forestry) is heated up to extremely high temperatures without oxygen, it turns into a charcoal-like material known as biochar. The material has a long history—indigenous communities in South America used it at least 8,000 years ago in farming, because when it’s added to the soil, it helps plants grow. But it’s also increasingly becoming one tool to help tackle climate change.

How does it store carbon?

Plants suck up CO2 as they grow, but that CO2 is normally released again quickly—if crop waste stays in a field after harvest, it will rot and release emissions. The same thing happens with fallen branches in a forest, or organic waste in a landfill. But if organic material is turned into biochar, that stops most of it from breaking down. “That process essentially takes part of the carbon in the original biomass and locks it into a very stable form that will reduce degradation of the carbon for hundreds or thousands of years,” says Thomas Trabold, a professor at Rochester Institute of Technology and one of the coauthors of the new study.

Where can it be produced?

The equipment that makes biochar can be used either at a small scale—at an individual farm, for example—or in larger facilities that collect waste from multiple sources. For the lowest carbon footprint, it makes sense to have a location that’s near the source of the organic waste and near the places where the biochar will later be used. To calculate how much biochar could be produced globally, the study looked at how much crop waste and other organic waste exists in 155 countries. In the U.S. alone, there’s the potential to produce enough biochar to sequester nearly 400 million metric tons of CO2 a year.

How does biochar help on farms?

Under a microscope, biochar looks like a sponge. If it’s added to soil, the spongy structure helps it hold water and nutrients, so farmers need less irrigation and fertilizer. (Fertilizers are another large source of emissions; the new study didn’t add up that benefit.)

It also can have other benefits beyond farms. Biochar companies can use wood cleared from forests at risk of wildfires, for example. And the biochar itself can also be used in other ways, including as an ingredient in concrete to help make the material stronger while it stores carbon.

What are the advantages compared to other types of carbon removal?

Biochar is considered a relatively permanent form of carbon storage, unlike planting trees that face the risk of later being cut down or burning in a forest fire. It’s also cheaper than technology like direct air capture, massive machines that suck CO2 out of the air. Equipment to produce biochar isn’t complicated to build. “What makes biochar interesting is it is one of the few sort of near-term-scalable removal credits,” says Justin Cochrane, CEO of Carbon Streaming, the company that helped finance the project in Waverly, Virginia.

Why isn’t it widely used now?

The cost has been a barrier in the past. But because of the ability to sell carbon credits now, that’s changing. “The industry existed for at least a decade with no means of financial reward . . . for all the carbon removed, we couldn’t get a dime for it,” says Josiah Hunt, CEO of Pacific Biochar, a company that makes biochar from sources like wood cleared from forests to prevent fires. “Since 2020, there has been a profound change in the biochar industry allowing for companies not only to survive but thrive.”

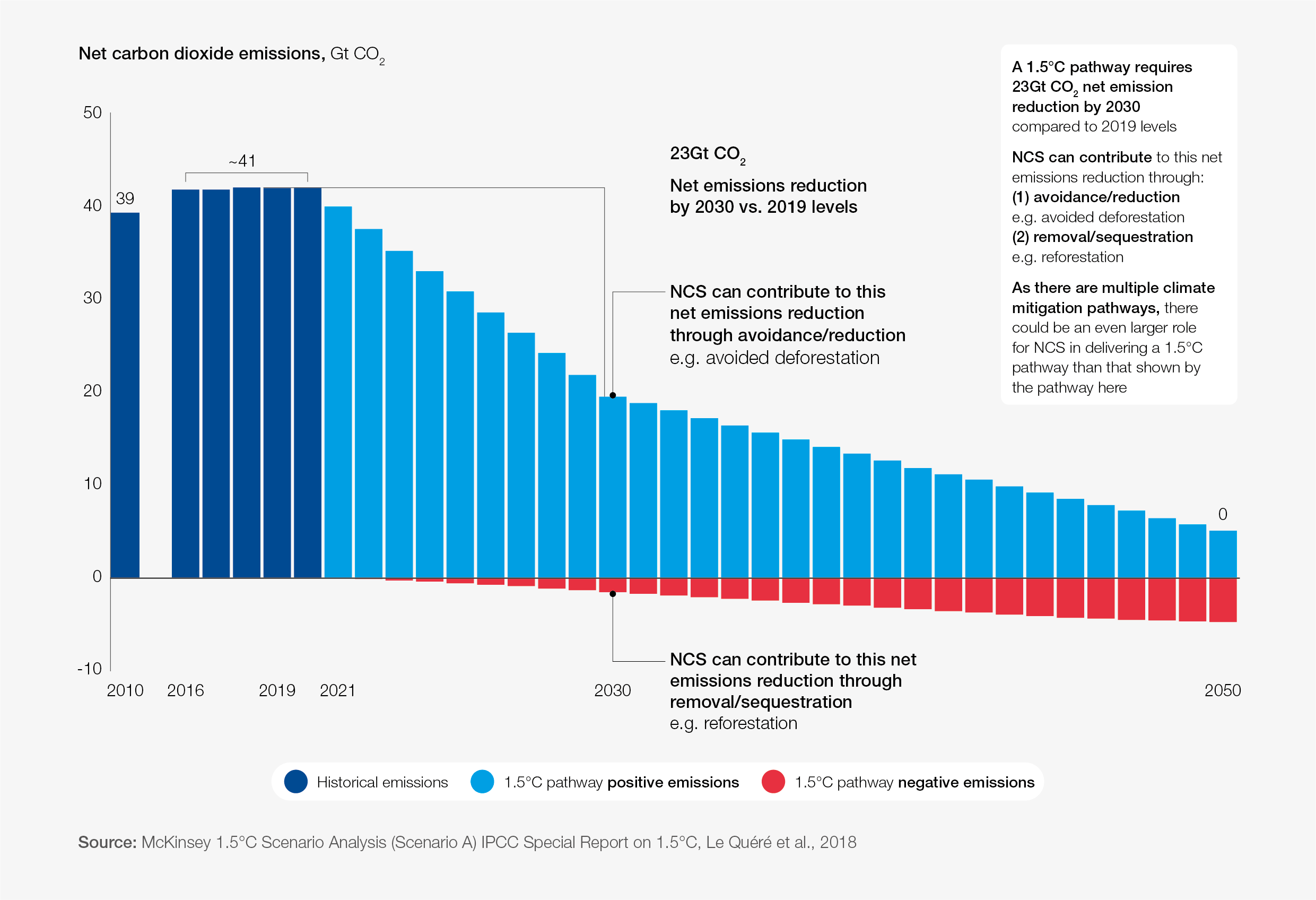

How does it fit into the bigger picture of tackling climate change?

The most critical piece of climate action is reducing emissions—most of which will happen by ditching fossil fuels. But as emissions drop, we’ll still need to remove CO2 from the air, both to deal with emissions that are difficult to eliminate immediately and to eventually begin to remove excess CO2 that’s built up in the atmosphere. Biochar is only one piece of the solution. But its potential to remove 6% of global emissions is significant. That’s equivalent to the climate pollution from more than 800 coal power plants, or nearly three times as much as the CO2 emissions from the airline industry.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Industries in DepthSee all

Robin Pomeroy and Linda Lacina

April 29, 2024

Robin Pomeroy

April 25, 2024

Daniel Boero Vargas and Mandy Chan

April 25, 2024

Abhay Pareek and Drishti Kumar

April 23, 2024

Charlotte Edmond

April 11, 2024