What are 'sponge cities' and how can they prevent floods?

Urban areas can prevent flooding due to climate change by becoming 'sponge cities'. Image: Patrick Tomasso/Unsplash

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

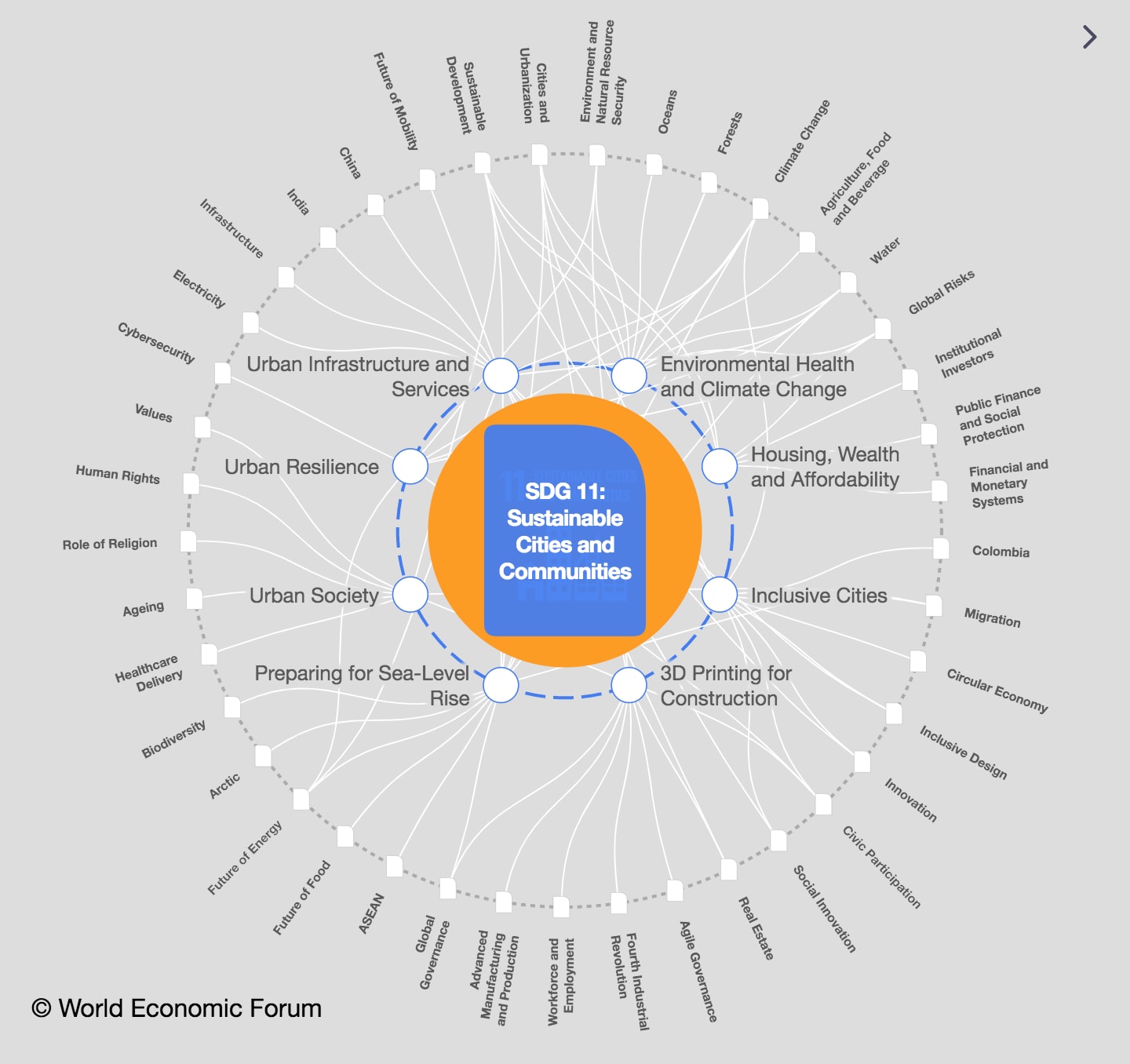

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- A new AI-based study compares cities' trees and lakes to how much concrete they have, to gauge their ability to respond to climate shocks.

- 'Sponge cities' are urban areas with abundant natural areas such as trees, lakes and parks - or other good designs intended to absorb rain and prevent flooding.

- Experts say cities need to be designed with this in mind as a growing number of urban areas are experiencing devastating floods due to climate change.

As climate change brings increasing flood threats, cities need to be designed like giant sponges that allow water to drain away safely, researchers say.

A first-of-its kind study used artificial intelligence to rank seven major cities on their 'sponginess' - in this case, the amount of natural space they have that can easily absorb rainwater.

Here's what sponge cities are and why they matter:

What are 'sponge cities'?

The term "sponge cities" is used to describe urban areas with abundant natural areas such as trees, lakes and parks or other good design intended to absorb rain and prevent flooding.

Interest in harnessing nature - or using "nature-based solutions" - to tackle climate shocks has grown in popularity in recent years.

Cities as diverse as Shanghai, New York and Cardiff are embracing their "sponginess" through inner-city gardens, improved river drainage and plant-edged sidewalks.

Why do sponge cities matter?

A growing number of urban areas are experiencing devastating floods as climate change brings heavier rainfall and growing flood risk.

A recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report said 700 million people already live in areas where rainfall extremes have increased, a number expected to grow as global temperatures rise.

In 2016, flash floods in Nairobi left streets submerged, trees uprooted and buildings in heaps, while Tropical Storm Elsa flooded New York in 2021. Both storms disrupted livelihoods and killed dozens.

How is the World Economic Forum supporting the development of cities and communities globally?

An equal benefit of sponge cities is that they can hold more water in rivers, greenery and soil instead of losing it to evaporation, meaning they are more resilient to drought.

Natural ways to absorb urban water are about 50% more affordable than man-made solutions, and are 28% more effective, according to earlier research by global design firm Arup and the World Economic Forum.

How is "sponginess" measured?

Researchers at Arup measured how much of seven major cities was covered by 'blue and green infrastructure' including grass, trees, ponds and lakes, and how much was covered in 'grey infrastructure' such as concrete, pavement and buildings.

Arup also looked at the type and texture of urban soil to assess how much water it could hold, as well as plant cover, which can help retain water and prevent runoff.

They used satellite imagery, artificial intelligence and machine learning to make the calculations. Arup said its AI digital mapping tool, Terrain, is 80% faster than manually mapping a city's landscape.

What were the findings?

The seven cities analysed were New York, London, Singapore, Mumbai, Auckland, Shanghai, and Nairobi.

Each was given a "sponginess" percentage of 1-100%. Cities with higher ratings can absorb more water during rainfall.

New Zealand's Auckland came out top with a 35% sponge rating - largely thanks to its stormwater systems, many golf courses, green parks and good-sized residential gardens.

It was followed by Nairobi at 34%, while New York, Mumbai and Singapore tied third with 30%, and Shanghai fourth with a 28% sponge city rating. In last place was London, at 22%, mainly due to high levels of concrete and poor soil absorbency.

How can cities become 'sponge cities'?

A city's sponginess is not set in stone. Adding more parks, trees, other greenery or natural drainage can boost a city's absorbency and make it more flood- and drought-resilient.

Many cities are adding green spaces to increase sponginess and deliver other benefits, from cleaner air to wildlife habitat and places to escape summer heat.

Landslide-hit Freetown, Sierra Leone's capital, for instance, is planting trees to help prevent future disasters, while Tirana in Albania is creating a ring forest to clean the air and halt urban sprawl.

Digital mapping tools can allow cities to quickly gauge the best use of their available space - from rainwater harvesting to ponds and inner-city gardens - as well as the risks in not doing so.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Climate ActionSee all

Ewan Gribbin and Deepanshu Singh

July 26, 2024

Gabi Thesing, Ian Shine and David Elliott

July 25, 2024

Luis Alvarado

July 24, 2024

Kate Whiting

July 23, 2024

Natalie Marchant and Julie Masiga

July 19, 2024