The surprising decline in US petroleum consumption

US oil production has transformed itself fundamentally in the past decade. Between 1970 and 2008, US crude oil production fell by nearly half as conventional wells were depleted. Since 2008, however, production has rebounded from 5 million barrels per day to an average of 8.7 million barrels per day in 2014. The almost entirely unexpected increase – largely attributable to technological innovations such as advances in horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing, and seismic imaging – has helped the US become the world leader in oil production.

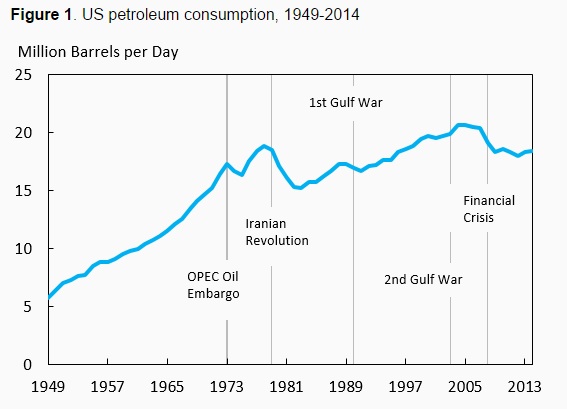

Whereas the developments in oil production have been widely reported and appreciated, far less attention has been paid to US petroleum consumption’s remarkable decline relative to both recent levels and past projections — one of the biggest surprises to have occurred in global oil markets in recent years. Petroleum consumption in the US was lower in 2014 than it was in 1997, despite the fact that the economy grew almost 50% over this period. As illustrated in Figure 1, consumption rose steadily from 1984 through the early 2000s, peaking in 2004 before decreasing in conjunction with rising oil prices.

Figure 1. US petroleum consumption, 1949-2014

Source: Energy Information Administration.

Unexpected

The levelling off of US petroleum consumption was largely unanticipated. In 2003, the US Energy Information Administration, which provides some of the most influential and well-regarded analysis in the field, projected that consumption would steadily grow at an average annual rate of 1.8% over the subsequent two decades. Consumption in 2025 was projected to be 47% higher than its 2003 level. The actual path that consumption has taken, however, diverges dramatically from this projection (Figure 2). Consumption in 2014 was actually slightly below 2003 consumption, and about 25% below the projections for 2014 that were made in 2003. We refer to this as the 2014 consumption surprise. Moreover, the difference between the actual and projected consumption in 2014 – 6.4 million barrels per day – is almost double the unexpected production increase over the same period (3.4 million barrels per day). The surprise consumption reduction frees up roughly $150 billion (2014 dollars) for spending on non-petroleum goods and services. There is even greater divergence in longer-term projections – the most recent projection for 2025 is 34% lower than the projection made in 2003. This 2025 consumption surprise frees up roughly $250 billion for spending on other things.

Figure 2. Total US petroleum consumption, 2000-2025

Source: Energy Information Administration’s Annual Energy Outlook.

The surprising decline in consumption is an almost uniquely American story. In percentage and absolute terms, the 2014 and 2025 surprises in the US are much larger than those observed in many other countries and regions of the world. For example, the consumption surprise for European OECD countries is about half that of the US, amounting to about 13% of petroleum consumption in 2015 and declining slightly to a projected 12% in 2025. For other OECD countries the surprises are even smaller, at 7% and 11% in 2015 and 2025. The consumption surprises for Japan lie just below those of the US.

The objective of our recent report (CEA 2015a) is to identify the mechanisms behind the large decrease in US petroleum consumption relative to past projections. Quantifying the underlying causes of the remarkable consumption decline improves understanding of why the consumption path has changed, how it might evolve in the future, and the role that public policy might play in further change. Petroleum consumption accounts for about 40% of US energy-related carbon dioxide emissions, and projections of long-run greenhouse gas emissions from petroleum consumption are highly dependent on the drivers of the consumption decline. If the Great Recession were the primary driver, for instance, we would expect petroleum consumption to return to past trajectories as the economy recovers, causing consumption-related emissions to rebound. On the other hand, if fuel economy standards were the primary driver, consumption and associated greenhouse gas emissions might continue to decline.

Decomposing the consumption surprises

As illustrated in Figure 3, the transportation sector accounts for 80-90% of the 2014 and 2025 petroleum consumption surprises. The industrial sector accounts for most of the remainder, at around 20% in 2014 and 7% in 2025, while the residential and commercial sectors account for a combined 4% of the surprise in both years. While other sectors experienced similar percentage surprises as the transportation sector, because they consume considerably less petroleum, they do not contribute nearly as much to the overall story. Our main analysis includes renewables such as ethanol in total petroleum products consumption, but the surprise reduction in the consumption of oil derived from fossil fuels is even larger than the surprise reduction in petroleum consumption because of the increasingly large share of petroleum derived from renewables like ethanol. Excluding ethanol, the size of the overall petroleum consumption surprises would be roughly 0.6 million barrels per day larger in both 2014 and 2025, and equal to 7 and 11 million barrels per day.

Figure 3. Decomposition by sector

Source: Energy Information Administration; CEA calculations.

Within the transportation sector, declining vehicle miles travelled has had a greater effect on consumption than rising fuel economy to date, but the role of fuel economy grows through 2025 (in Figure 4 the fuel consumption rate, as measured in gallons per mile, is the reciprocal of fuel economy). In 2014, rising fuel economy explains roughly 25% of the consumption surprise, and vehicle miles travelled explain the remaining three quarters. In the 2025 projections, however, the factors are more comparable, with fuel economy accounting for 45% of the surprise and vehicle miles travelled accounting for 55%, demonstrating the growing rule of public policies like fuel economy standards in shaping fuel use.

Figure 4. Transportation sector fuel consumption rate and VMT decompositions

Source: Energy Information Administration; CEA calculations.

Figure 5 illustrates the contributions of each sector to the overall petroleum consumption surprises. In the figure, the transportation sector petroleum consumption surprise is decomposed further into the vehicle fuel consumption rate, vehicle miles travelled, and other factors such as aircraft consumption. In 2014, vehicle miles travelled is the single most important factor, accounting for just under half of the total petroleum consumption surprise. The importance of the fuel consumption rate doubles (in percentage terms) between 2014 and 2025. Because the transportation sector accounts for 80-90% of the two consumption surprises, and vehicle fuel consumption dominates consumption of other fuels in the transportation sector, we next discuss the factors that explain vehicle fuel consumption rates and miles travelled.

Figure 5. Overview of contributions to the 2014 and 2015 consumption surprises

Source: Energy Information Administration; CEA calculations.

A closer look at fuel economy and ‘vehicle miles travelled’

Two factors have contributed to rising vehicle fuel economy:

- Fuel economy standards; and

- Higher-than-expected gasoline prices.

Fuel economy standards explain up to 43% of the increase in fuel economy between 2003 and 2014, and will explain an even larger portion going forward as tighter standards set in. High gasoline prices —relative to 2003 projections — explain at least 17% of the fuel economy increase to date.

According to new analysis from the Council of Economic Advisors (an agency within the Executive Office of the President of the United States) much of the change in the trajectory of vehicle miles travelled can be explained by changes in demographics, such as the ageing of the population and the retirement of the baby boomers, and by changes in economic variables like income, employment status, and gasoline prices (CEA 2015a).

The Council of Economic Advisors used panel data on the driving behaviour of households from 1990 through 2009. The analysis projects the path of vehicle miles travelled since 1990, given only information on demography and economic factors like income and gasoline prices. Absent such information, a linear trend would have simply predicted a continued increase in vehicle miles travelled from 1990 forward, as illustrated by the green line in Figure 6. Because of the ageing of the population and other demographic factors, the model predicts that vehicle miles travelled levels out in the late 1990s and starts to fall after 2001. However, changing demographics and economic factors are not the entire story. In fact, the red and blue lines in the figure show that actual vehicle miles travelled was slightly higher than the model’s prediction, suggesting that, if anything, the factors that are omitted from this model have led to more driving and not less.

There is also evidence that the effects of demographics on vehicle miles travelled have changed as well. For example, individuals younger than 40 drove 5% less in 2009 than individuals who were younger than 40 did in 1990. Because demographics and economic factors themselves are easier to project than the changes in their impacts, the importance of these changes presents a challenge to projecting future petroleum consumption.

Figure 6. Actual and predicted VMT per household using changes in household demographics and economic factors

Source: National Household Travel Survey; CEA calculations.

A surprising decline

Documenting the surprising decline in US petroleum consumption, both in absolute terms and relative to past projections, we find that the transportation sector explains most of the surprise between previous projections of petroleum consumption and actual data, as well as the surprise between previous and the most recent projections. Miles travelled by passenger vehicles plays an important role in the transportation sector, but rising fuel economy (implying declining fuel consumption rates) has a large influence that is growing over time.

Between 2003 and 2014, gasoline prices explain a large share of the fuel economy increase of the light-duty fleet. However, over time we expect fuel economy standards to have a growing influence on fuel economy — both for the light- and heavy-duty fleets. Fuel consumption from the heavy-duty fleet accounts for one-fifth of total transportation sector consumption, and is the fastest growing component in the transportation sector. New heavy-duty fuel economy standards that the Administration has announced will reduce actual transportation sector consumption relative to even the 2015 projections, which do not reflect these new standards.

Given the importance of miles travelled in explaining the surprises, we use household survey data to present new evidence on the factors underlying the changes. Demographics appear to explain a very large portion of the vehicle miles travelled developments, but we also find evidence that the effects of demographics and economic variables on vehicle miles travelled have changed over the past 20 years. Such changes present a major challenge to projecting future petroleum consumption.

Importantly, there has also been a large unexpected increase in ethanol consumption relative to 2003 projections. Given the large and growing importance of fuel economy standards and ethanol, this analysis suggests that federal government policy has, and will continue to have, a substantial effect on US petroleum consumption and on overall carbon emissions reductions by the transportation sector.

President Obama’s clean energy strategy has made concrete strides to reduce petroleum consumption and shift the US economy to a low carbon future through policies like fuel economy standards and tax credits for renewable energy (CEA 2015b). The president remains deeply committed to providing a clean and secure energy future for our children and will continue to act to reduce carbon emissions through policies like the Clean Power Plan and engagement with international allies.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

References

CEA (2015a), Explaining the U.S. Petroleum Consumption Surprise, Washington, DC: Council of Economic Advisors.

CEA (2015b), Economic Report of the President, Washington, DC: Council of Economic Advisors.

Energy Information Administration (various years), Annual Energy Outlook, Washington, DC.

This article is published in collaboration with VoxEU. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Lydia Cox is a Research Economist at the Council of Economic Advisers. Jason Furman is the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. Joshua Linn is currently serving as a Senior Economist at the Council of Economic Advisers. Maurice Obstfeld is the Class of 1958 Professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley.

Image: Traffic moves through the rain along interstate 5 in Encinitas, California. REUTERS/Mike Blake.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.