Why doing good makes for good business

There are many ways of achieving social impact, and many ways that people organize themselves to do so. Sometimes this is through informal associations, like community groups; sometimes it’s through more formal ventures, such as charities and cooperatives.

Increasingly, there’s a third group: business. A growing number of people are choosing to make a difference through commercial enterprise. And interestingly, it’s in line with what consumers, employees and investors want. In the United Kingdom, more than 30% of consumers look for products based on their environmental or social impact. Meanwhile, some 60% of millennials choose their workplace based on its purpose.

This is nothing new: all business has an impact, and corporate social responsibility has been around for years. What seems to be different, though, is that more and more people are saying that the primary purpose of their business, or the way they do business, is a social or environmental cause. So achieving social impact sits at the core, rather than at the sides. Some people call this “mission-led” business.

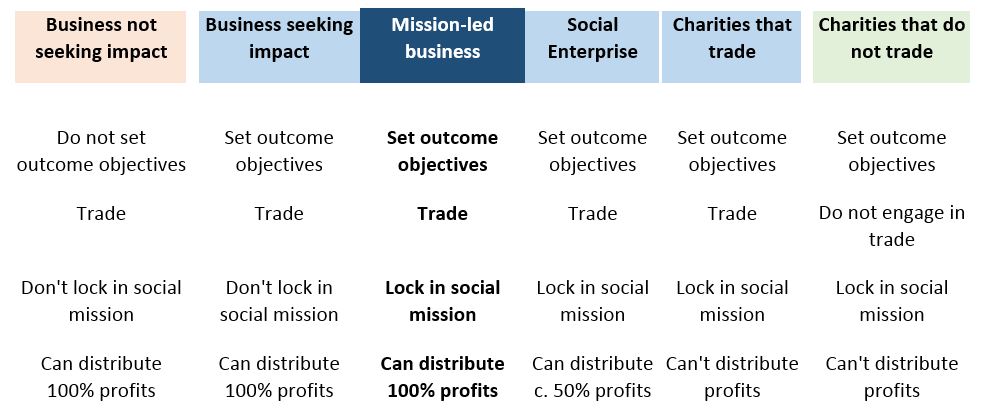

The chart below shows the different types of impact organizations and how they operate.

There are examples from all over the world. Warby Parker, a manufacturer in the United States, distributes a pair of glasses in a developing country for each pair it sells in a developed one. Natura, a Brazilian beauty and cosmetics firm, is working to become carbon neutral. Bridges International Academies, founded in Kenya, educate underprivileged children across Africa and Asia. They’re one of the largest chains of primary schools in the world.

The numbers back this up. Take the United Kingdom, for example, where there are 180,000 regulated social-sector organizations. They have a combined annual income of more than £40 billion and a workforce of over 800,000 people. Surveys indicate there are another 180,000 businesses that claim a social or environmental cause. These enterprises employ 1.5 million people and have an annual turnover of more than £120 billion. What’s more, in the UK, mission-led businesses seem to be among the fastest-growing start-ups.

All of which, undoubtedly, is great news. The more organizations dedicated to achieving social impact the better.

But it also raises some important questions for the rest of us – in particular, how do we know that an organization is “social”? And how do we know it will carry on being social? These are sometimes referred to as questions of “signal” and “lock”.

To some extent, “signal” is the easy one. Many of us know to look out for the word fairtrade to know that something is, broadly speaking, a good thing. New industry initiatives, like B Impact Assessments, aim to communicate the standards of a company.

More complicated is “lock”, as there are a few different ways we can think about this – profit, mission and performance.

- Profit lock: is probably the first thing that comes to mind when we think about social organizations (though it’s not the profits as such, it’s what you do with them). This is the idea that profits can be constrained to support and protect social purpose. In many countries, organizations like charities aren’t allowed to distribute any profits, and social enterprises are often defined by the fact that they put the majority of their profits back into their social mission. Most businesses don’t have a profit lock.

- Mission lock: is probably the second thing that comes to mind. This is the idea that an organization sets its rules (typically its governing articles) so that it is “locked” into achieving a social or environmental mission. Sometimes this is regulated, but it doesn’t have to be. And while some countries allow businesses to prioritize this kind of social mission, many do not.

- Performance lock: is a bit more complex. This is the idea that the organization’s business model is intrinsically linked to supporting their social purpose. So, for example, only selling things that achieve social or environmental impact. The aim of a performance lock is that profit equals purpose, and vice versa.

Some organizations have all three locks. Others say that one or two is enough. Some have none, and say that as long as they’re happy with how they are achieving social impact, it doesn’t really matter what others think.

And within that choice lie all sorts of tensions. For example, a profit lock seems to suggest that profit is dangerous. A mission lock seems to suggest that intent might be more important than impact. A performance lock seems to suggest that social need tracks neatly to what people or governments want to buy. All of these are questionable.

So why does this matter? Well, for a start, the growing numbers of mission-led businesses are having to tackle these choices head on. Most are choosing not to take profit locks – in some instances, to allow for ease of growth and raising investment; in many, a rejection of the idea that private benefit is incompatible with public good.

All of which raises questions for consumers. If unable to depend on profit lock, we need to be confident that the tools exist to ensure a business keeps to its social mission (short answer: they probably do), and that countries have the appropriate legal structures to enforce these (short answer: most don’t yet).

But these are all addressable concerns. More importantly, the emergence of these mission-led businesses has to be seen as a good thing. In their potential to bring further scale, sustainability and talent to tackling social problems, they’re a powerful addition to the world of charities and social enterprises. And although names matter, it’s like with any good party: the more the merrier.

Author: Kieron Boyle is Head of Social Investment at the UK Cabinet Office

Image: Volunteers give toys to the needy during a food and toy distribution at the Legiao da Boa Vontade social centre in Lisbon, December 19, 2012. REUTERS/Rafael Marchante

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.