Three risks to the Chinese economy

Clearly, the debt issue must be addressed. Image: REUTERS/Bobby Yip

After a decades-long “growth miracle,” China’s economy has lately become a source of mounting concern. Some factors – from high corporate debt to overcapacity in the state sector – have received a lot of attention. But three less-discussed trends point to still other threats to the country’s economic growth.

First, despite the decline in GDP growth, total social financing – and especially bank credit – has increased. This relates directly to China’s debt problem: the continual rolling over of large liabilities creates a constant demand for liquidity, even if actual investment does not increase. Such “credit expansion” – which is really just rolled-over debt – is not sustainable.

Clearly, the debt issue must be addressed. And the Chinese government has been working to do so, implementing policies aimed at supporting debt restructuring. For example, the central government has helped local authorities to replace CN¥3.2 trillion ($471.9 billion) of risky debt in 2015, and an expected ¥5 trillion this year. Its corporate debt-for-equity swap plan could augment the impact of these efforts.

But these strategies cannot fully address China’s debt problem, not least because the largest share of debt in China is held by state-owned enterprises. One important solution that has not yet been proposed would involve a far-reaching restructuring of large SOEs. The sale or transfer of state-owned assets would cover liabilities, breaking the state sector out of its debt-ridden status quo. This approach would also create an opportunity to advance privatization, which could bolster innovation and competitiveness.

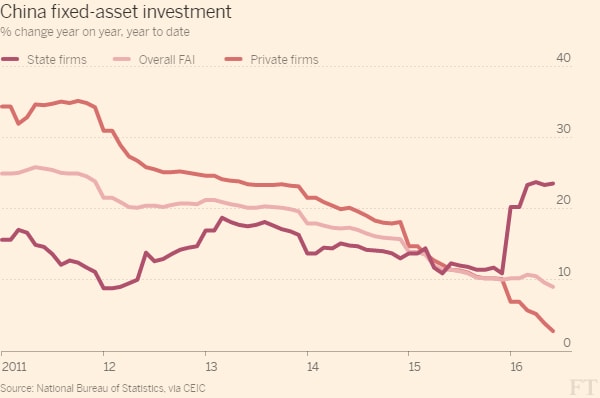

The second risky trend is the rapid decline in fixed-asset investment, from 20-25% to around 8% today. The decline has been particularly marked in the private sector. In 2002-2012, growth in private-sector investment averaged around 20%; by the end of last year, it amounted to just 10%, and from January to August of this year, it reached just 2.1%, including a stunning 1.2% contraction in July. Investment in real estate has also slowed, having increased by just over 1% last year, owing to a number of policy constraints.

Given that private investment accounts for at least 60% of total investment in manufacturing, this will undoubtedly have macroeconomic consequences. And, though double-digit growth in state-sector investment will temper the overall effect, this trend also reflects problems with state-sector dominance. Private companies struggle to gain credit from state-owned commercial banks and are at a disadvantage in the direct financing market. Moreover, private firms are blocked from entering SOE-dominated, capital-intensive, and high-end service industries. In most of the modern service sectors, the share of non-state actors remains small, limiting private investment.

The third trend that should be worrying China is that unemployment remains relatively steady. Because the unemployment rate is not excessively high, this might seem like a good thing. But it reflects some negative trends – starting with long-term weakness in productivity growth.

China’s productivity growth rate, which averaged 8% over the last 20 years, may have dropped now to less than 6%. And the country is not exactly positioned for a surge in productivity. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the services sector has far outpaced manufacturing in employment growth since 2010, a reversal of the earlier trend.

Given the need for China to move away from manufacturing, this is not altogether bad news. But most of the service-sector jobs being created are in low-end, low-productivity activities. Worse, these are often informal jobs characterized by high turnover, which impedes long-run human-capital accumulation.

Stable employment levels in China also reflect – yet again – shortcomings in the state sector. Few workers have been released from SOEs, despite the overall growth slowdown. In other words, there is considerable hidden unemployment in China’s state sector, which is already plagued by other kinds of overcapacity.

China has no easy option for addressing this problem. If the government continues to prop up SOEs, especially “zombie” firms, the concentration of a large number of workers in low-productivity, stagnant SOEs will continue to undermine productivity growth. But if China pursues state-sector restructuring, unemployment will rise. And, once unemployed, state-sector workers tend to take much longer to find a new job than their private-sector counterparts do.

Yet state-sector restructuring seems unavoidable. Indeed, it would help to address a number of the most fundamental challenges facing China, from debt and overcapacity to lack of competitiveness.

To be sure, some claim that SOEs should be allowed to continue their operations, citing their huge profits. But those profits are the result of their monopoly status and massive state investment, which brings lower returns than private-sector investment. That is why progress on SOE reform is so urgent, regardless of the short- and even medium-term challenges that it might create.

Two decades ago, then-Premier Zhu Rongji began to pursue such reform, with the goal of bolstering the efficiency of SOEs and creating space for private-sector investment. But the reforms were incomplete, and some have even been rolled back, with SOEs regaining market share in some cases.

In 2013, the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China took up the mantle, with a plan to reform SOEs through mixed ownership. But here, too, progress has been inadequate. And, in fact, without a strategic reorganization of SOEs, mixed ownership will become a feature of only non-essential sectors.

If China is to succeed in its economic restructuring, industrial upgrading, and expansion of high-productivity services, the role of SOEs needs to be once again limited to a few relevant sectors. Only then can China recapture its dynamism and keep its economic growth on track.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

China

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Rishika Daryanani, Daniel Waring and Tarini Fernando

November 14, 2025