What a football shirt tells us about globalization 4.0

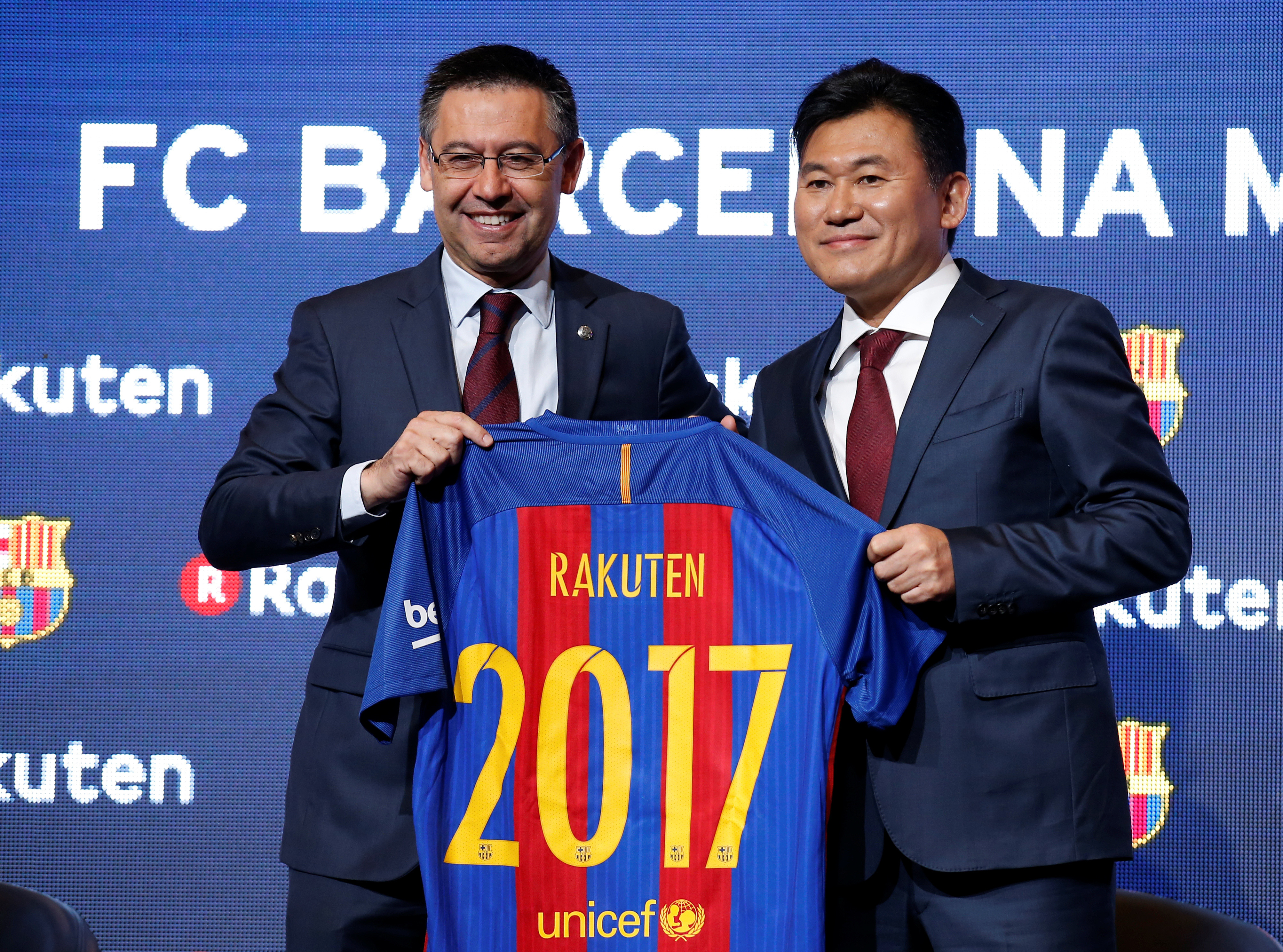

Rakuten’s sponsorship deal with FC Barcelona began on July 1, 2017 Image: REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon

It was an eye-watering deal. Starting in the 2017-2018 season, Japanese internet service provider Rakuten became the main global sponsor of FC Barcelona for a record €55 million per year. Only one other company, kit provider Nike, also had its logo on the iconic shirts of the “blaugrana”. They made a powerful pair of global sponsors.

But the two companies may never have been around together, had Rakuten’s digital globalization begun 50 years earlier, or Nike’s Phil Knight started importing shoes in 2017 instead of 1964. To understand why, we need to look at the state of globalization when Nike was founded, and contrast it with today.

When Phil Knight started Blue Ribbon Sports in 1964 - the company that seven years later would become Nike - it wasn’t as easy to buy a product from abroad as it is today. China was an agricultural economy that produced barely any exports. Its rise as “the factory of the world” - let alone as the home of tech platforms - was decades away.

And it wasn’t just China that wasn’t globalized. As a percentage of global GDP, trade stood at approximately the same level as a century earlier. Worldwide, less than one out of ten dollars of added value came from trade. The US was further ahead than most advanced economies, as many countries were still recovering from the Second World War, but the overall picture was one of local production.

The early days of globalization explain Nike’s first business model. After being impressed by the running shoes of Japanese sports company Onitsuka Tiger, Knight offered to distribute the Japanese shoes in the US. Tiger would produce the shoes in Japan, and Knight would arrange the logistics, distribution and marketing in return for any profits. It was global trade and arbitration in its simplest form.

In the 50 years since, there have been many structural changes to the global economy, as well as to Nike. The company stopped being a Onitsuka distributor just a few years into the joint venture, and produced its own line of shoes instead. Nike is now the largest sports company in the world, and its supply chain model with suppliers and distributors in dozens of countries is the norm for global companies.

This is the modern global supply chain. Your sneakers may be designed in Portland, Oregon (home to Nike’s headquarters). The raw materials may be sourced from a dozen or so countries - wherever they are best and cheapest. The shoes may be produced in Viet Nam or Indonesia. Their regional distribution may be handled in, say, Belgium. And the sale takes place in your local shoe shop in Germany.

As global trade gained in importance, tariffs dropped, and such globalized supply chains became the norm, not just for Nike, but for most multinationals. Trade now stands at close to a quarter of global GDP - its highest level ever - and despite a recent surge in more protectionist governments, new trade deals ensuring the physical flow of goods across borders still are signed every month. Yet if trade is to get another boost, it's more likely to take a different form than the global supply chain. It could come from digital trade, carried out by companies like Rakuten.

Rakuten was founded in 1997 as an online shopping mall or “ichiba”. Much like Amazon in the US, Alibaba or JD.com in China, Flipkart in India or Zalando in Germany, it engaged in plain e-commerce. You could order a product online and have it delivered to your home. In just a couple of years, it became the largest e-tailer in Japan, with 95 million customers. (Japan’s entire population is 127 million.)

But e-commerce stopped being a domestic play a long time ago, and so did Rakuten. After a period in which it focused mostly on Japanese sourcing and sales, Rakuten started international expansion in 2010. It bought similar e-commerce platforms in France, Germany, Brazil, Malaysia and other countries. By 2018, it claimed 1.2 billion users across 28 countries. It started to diversify to other verticals, including chat apps, e-book platforms and online content production.

It is in this light that we should see global sponsor deals such as Rakuten’s with FC Barcelona. E-commerce is increasingly happening across borders, with consumers buying goods direct from a manufacturer in another country. At the same time, e-commerce is also expanding in the virtual realm, where digital goods can be bought and sold everywhere in the world, no matter their origin. This is the new face of globalization. To be successful at it, global recognition is key.

When Rakuten signed its deal with FC Barcelona in 2016, it said it did so as “an important part of its plans for global expansion”. No wonder. According to a McKinsey report that year, “approximately 12% of the global goods trade [was by then] conducted via international e-commerce”. That number has likely risen fast in the years since (no recent estimates exist).

With more than four billion people now estimated to be online worldwide, and millions added every month, it seems a foregone conclusion that digital trade in all its forms will continue to rise for many years to come. It is true as much for Rakuten in the US or Europe, where it sells Japanese products direct to consumers, as for Alibaba, Amazon and other e-commerce players.

Just how this trade will happen, and how much of it will take place in the future, remains to be seen. No international organization currently has up-to-date, or even historical, statistics on digital globalization. However, there is a broad differentiation in digital trade:

- Digitally ordered and physically delivered, as with sneakers or football shirts

- Digitally ordered and digitally delivered, as with e-books or IT consulting tasks

What is certain is that the world has rapidly changed in the last 50 years. In 1964, Phil Knight could build a successful company by buying Japanese-made running shoes in bulk and selling them in the US. Today, any consumer can go to Rakuten.com in the US and buy Japanese-made Onitsuka Tiger shoes direct. The business model that worked in the 1960s likely wouldn’t work today.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that Nike’s globalization model is out of date. As a matter of fact, the same company that would undercut Phil Knight if he started today is helping Phil Knight’s successors sell their products in Japan and around the world. Go to Rakuten.co.jp, and you can buy Nike sneakers direct in Japan. And of course, Nike has its own global e-commerce store.

Perhaps it’s not all that odd, after all, that both companies in harmony decided to sponsor the then-most popular football club in the world on social media. Yet they should beware. Today’s winner can become tomorrow’s runner-up. Ask Barcelona. In 2018, a year after it launched the Rakuten-Nike shirt, it lost its place as most popular online club to Real Madrid. Digital globalization is huge, growing and certainly still changing.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Retail, Consumer Goods and Lifestyle

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.