Explainer: How catastrophe bonds help manage climate risks

Catastrophe bonds protect insurers from losses related to the climate crisis. Image: REUTERS/Octavio Jones

This article has been updated.

- Extreme weather events have become the new normal as a consequence of the climate crisis.

- Insurers use catastrophe bonds to shield themselves against losses from natural disasters.

- But less than 60% of global weather-related losses are insured, according to a World Economic Forum report, which lays out a roadmap to ensure the most vulnerable are not left behind.

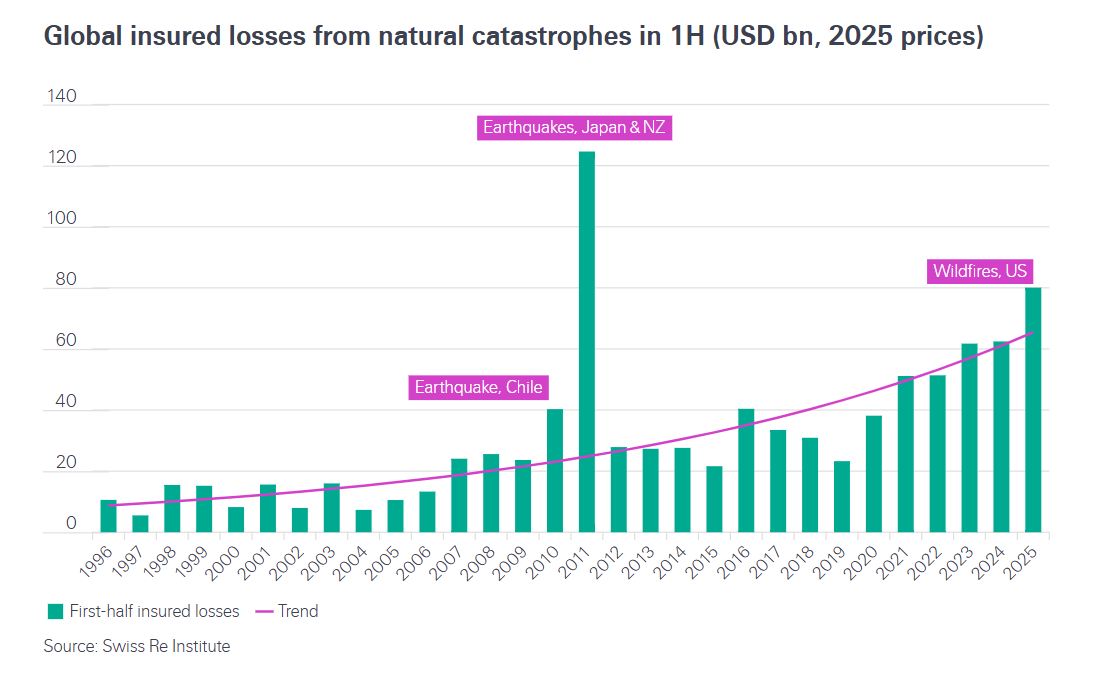

Global natural catastrophes, like this year’s LA wildfires and severe storms across the world, helped push insured losses to $107 billion in 2025, marking the sixth year in a row losses have exceeded $100 billion.

With extreme weather events becoming the new normal due to the climate crisis, insurance companies have had to adjust around this growing financial risk – with catastrophe bonds one of the solutions.

How do catastrophe bonds work?

Catastrophe bonds, or cat bonds as they’re often called, allow insurance companies to transfer the risk of natural disasters covered by their policies to investors – for a price.

They were first issued in the 1990s at a time when the insurance industry was reeling from a series of costly catastrophes including Hurricane Andrew, which had devastated Florida and the Gulf coast and driven some insurers out of business.

Since then, the cat bond market has grown steadily, as demonstrated by the chart below which shows cat bonds for property-related perils like hurricanes or earthquakes.

The money raised with these bonds is set aside to cover potential losses. If triggers that are spelled out in the contract – insured losses from a hurricane reaching a specific level, for example – are met, the insurer gets to use the money to offset what it has paid out to policyholders. In that case, it no longer has to repay the holders of the bond, who can lose their investment.

If the natural disasters covered by the bond don’t occur, the investors get their money back in full when the bond matures, usually in three to five years. And along the way, they collect regular interest payments.

Why do insurers like catastrophe bonds?

The main tool insurance companies use to offload risk is called reinsurance, whereby they buy policies from other insurers that limit their losses in case of a disaster. This prevents any one company from taking on too much risk.

But reinsurers, just like any insurance company, don’t always pay out on every claim. And the policies they sell typically last just one year. Catastrophe bonds, by contrast, are set up to remove ambiguities by setting out clear triggers for payment, as in parametric insurance, and allowing insurers to lock in the price of protection for a longer period of time.

The main attraction for investors is that these bonds pay higher interest rates than most other varieties, so they can potentially make more money. The other big benefit is that, because catastrophe bonds are tied to specific natural events, they provide returns that are largely unaffected by economic cycles and the ebb and flow of financial markets. That can make them a useful buffer when other investments sour.

Catastrophe bonds aren't just for insurers

Insurers aren’t the only ones turning to catastrophe bonds. In 2021, the World Bank priced a bond that gave the government of Jamaica protection of up to $185 million against losses from named storms during three Atlantic tropical cyclone seasons. More recently, Jamaica received the full pay-out of $150 million from the World Bank’s cat bond after Hurricane Melissa swept through the Caribbean in October, causing widespread destruction. The cat bond will enable the country to rebuild.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power raised $30 million in 2021 to shield it from California wildfire losses. Its latest cat bond stands at $100 million, an amount which is not surprising when you consider that 83% of global insured losses for 2025 were due to natural disasters in the US, and mainly the LA wildfires.

Extreme weather and insurance

Despite these figures, it’s also true that less than 60% of global weather-related losses are insured, according to a World Economic Forum report, Insuring Against Extreme Heat: Navigating Risks in a Warming World. This is placing a $150 billion financial burden on world governments and communities, it says. And while extreme heat is currently the deadliest climate risk, responsible for almost 500,000 deaths annually (more than floods, hurricanes, earthquakes and wildfires combined), the cat bond market for this area is less developed than for perils like hurricanes.

With the most vulnerable communities set to suffer the most as a result of, firstly, extreme weather events and secondly, a lack of insurance, it’s paramount that coverage becomes more accessible and affordable, says Christopher Townsend, Member, Board of Management at Allianz. The report encourages the insurance industry to utilize AI to better support prevention and risk mitigation.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Climate and Health

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Global RisksSee all

H. Charles J. Godfray and Douglas Gollin

January 30, 2026