How Latin America can break the innovation paradox and jumpstart growth

Latin America has an “innovation paradox” that is in desperate need of solving. Image: Pexels/Marina Leonova

- The 2025 Nobel Prize reinforces innovation and “creative destruction” as the primary drivers of growth.

- Marking 10 years, the World Bank’s Productivity Project builds on these findings and distills frontier research into actionable policy for developing nations.

- Latin America must solve its “innovation paradox” by pairing stable business climates with entrepreneurial capabilities.

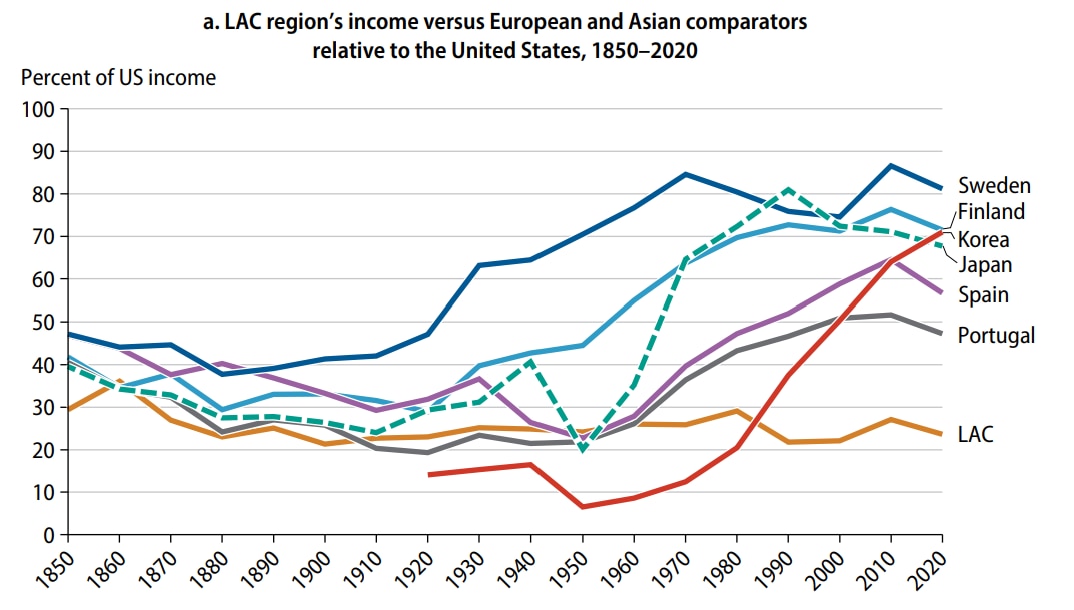

Having had decades of engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), we are seeing the region’s success in breaking old patterns of economic instability, and a convergence towards a broad set of shared macroeconomic principles become evident.

And yet, frustration in the region is rising. Average growth, stuck near 2.5%, is the lowest of any region and too weak to create good jobs or advance social progress. Even Chile, often cited as a model of market-friendly reforms, has seen little productivity growth in over a decade. In this context, it is no surprise that we are seeing a renewed interest in industrial policies.

Frontier thinking on productivity

This persistent low-growth puzzle inspired the World Bank to launch the Productivity Project. It aims to distill frontier thinking on productivity into evidence that policy-makers in developing countries could use. Over 10 years, the series has explored what drives productivity, how innovation and entrepreneurship emerge, where agriculture and services still hold unrealized potential, how space and cities shape growth, and why risk finance remains scarce.

Across these topics runs a common message about the centrality of technological adoption and creative destruction for growth, ideas now spotlighted by the 2025 Economics Nobel Prize, awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt for their groundbreaking research into the mechanics of innovation-driven economic growth.

The Productivity Project frames this discussion around two elements. First, building market-friendly enabling environments. Second, ensuring that those environments are populated by capable entrepreneurs backed by institutions that encourage innovation.

These two elements and their interactions are key to explaining why growth outcomes can differ so much among similar countries, or, strikingly, within identical sectors: Japan and the United States leveraged copper for industrialization; Chile could not. Norway used oil and gas revenues to drive and diversify growth; Brazil has been less successful. Korea and Mexico began assembling electronics at roughly the same time, but only one has invented a world beating cellphone. These cases suggest that, rather than trying to pick “high- growth” sectors, policy should focus on how countries produce, more than on what they produce.

The innovation paradox

As an example of this how, Peter Howitt argues that a nation’s ability to adapt existing technologies to its own context, and then develop new ones, ultimately determines whether it falls into a low- or high-growth “club”. LAC continues to find it difficult to do so. This has deep historical roots of the kind Howitt discusses and Joel Mokyr has explored in detail for Europe.

As my co-authors and I argued in a recent book, Reclaiming the Lost Century of Growth: Building Learning Economies in Latin America and the Caribbean, during the second industrial revolution, peer nations adopted the new emerging technologies and took off, while LAC slid into a low-growth club marked by limited diversification and dependency.

This trajectory of missed opportunities, and that of many other developing countries, gives rise to what the Project calls the “innovation paradox”. Despite potential returns to innovation often above 50%, and the potential to join the high-growth club, firms and governments invest too little in education, knowledge capital, managerial capabilities, R&D and new products – insufficient even to keep traditional sectors dynamic, much less build new ones.

Explaining persistent underinvestment

Why does this underinvestment persist? Part of the explanation arises from deficiencies in the first growth element: weak enabling environments that reduce the profitability of innovation and impede risk management, such as shallow financial markets, weak competition, poor infrastructure, macro uncertainty and limited worker skills. Howitt and Aghion argue that financial constraints can choke off investment needed to adopt technologies. China’s recent slowdown suggests that even vast state spending on innovation cannot overpower challenges in the business climate. Even in Europe, the report on European Competitiveness authored by Mario Draghi sees European innovation dampened by excessive and poorly designed regulation.

But critical as reforming the enabling environment continues to be, it is not enough and needs the second element: capable entrepreneurs and technical professionals to spot opportunities, manage risk and organize firms to create value, and innovation institutions to support them.

For instance, more competition does not automatically spur innovation. Aghion finds that stronger competition increases innovation only in firms near the managerial and technological frontier. LAC also lags here. Evidence from the surge of Chinese imports into Chile and Colombia suggests that LAC has far fewer of these frontier firms, around one-fifth of the share in the UK or France, implying a much lower growth “kick” from competition. Improving the enabling environment and building capabilities must proceed in tandem.

Why fortune favours the prepared

LAC can do more to seize whatever opportunities or meet whatever challenges are presented with 21st century technological innovation. It can follow the successes of Norway or Korea, both of which improved their business climates while developing the necessary capabilities and institutions. To paraphrase Pasteur: fortune favours the prepared.

The Productivity Project remains a useful tool for building that preparedness by bringing frontier insights, like those celebrated by the 2025 Nobel in Economics, into policy debates and helping LAC and other developing countries chart more dynamic paths forward.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Latin America

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Elizabeth Mills and Gayle Markovitz

January 30, 2026