Opinion

Polarization is one of the world's top risks. Jesse Jackson had answers 40 years ago

When examining coalition building models, Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition deserves attention. Image: REUTERS/Mike Segar/File Photo

Alem Tedeneke

Media Lead, Canada, Latin America and Sustainable Development Goals, World Economic Forum- Polarization is a major global risk that impacts various other societal and economic issues.

- Decades ago, the late US civil rights leader Jesse Jackson offered a path forward to coalition building.

- Jackson's organizing philosophy was straightforward: unity does not require sameness.

Unity and difference are often treated as opposites. Leaders are told to choose between broad coalitions and clear identities, between inclusion and coherence.

Forty years ago, the late Jesse Jackson rejected that premise.

As a prominent American civil rights activist, politician and religious leader, Jackson built what became known as the Rainbow Coalition on a different idea: that durable solidarity could be formed not by minimizing difference, but by organizing around it.

Coalition forged from difference, not despite it

Today, we talk about polarization like it is new – it isn’t. What is new is the scale and the stakes.

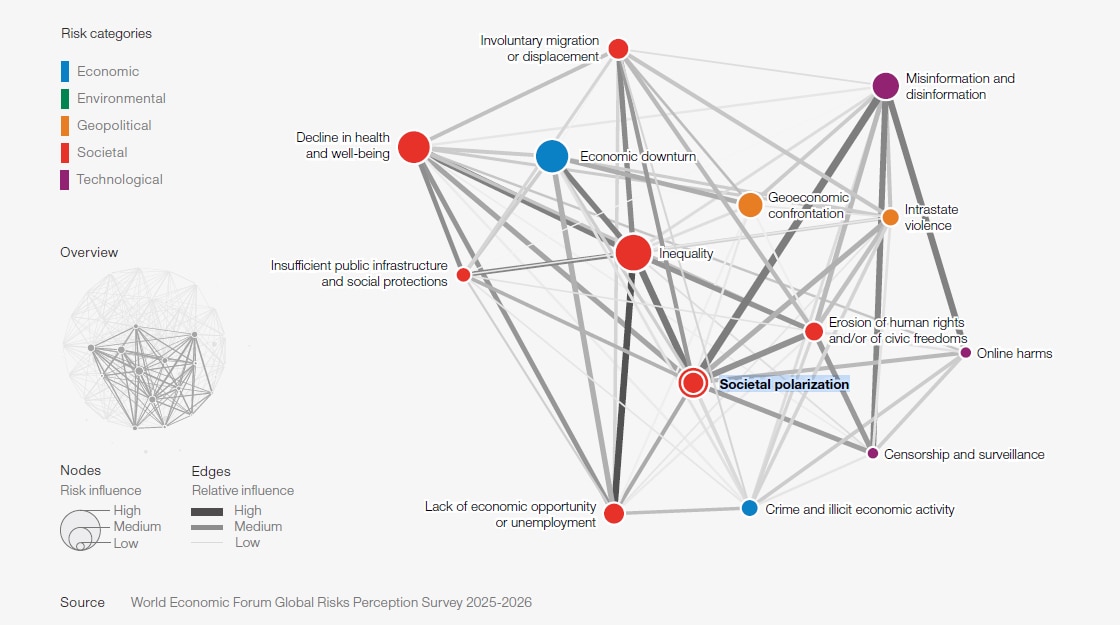

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2026 identifies societal polarization as a risk that does not operate in isolation. It connects to inequality, misinformation and the erosion of shared values. The report describes this dynamic as “values at war,” a phrase meant to capture how division is rooted in more than just policy debates.

So, when we look for coalition building models that have worked not in theory, but in practice, the Rainbow Coalition deserves attention.

When Jesse Jackson launched his presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988, the prevailing logic of political organizing was simple: build power within your base, speak to your constituency and don’t dilute the message. Jackson did the opposite.

The Rainbow Coalition brought together racial and ethnic minorities, working-class communities, young voters, rural communities and others who had been systematically sidelined. These were not groups with the same histories or the same grievances. What they shared was something more fundamental: economic insecurity, limited political voice and a political system that had largely moved on without them.

Moreover, Jackson spoke plainly and morally, often without hedging, to rooms that were not used to being spoken to that way. He campaigned in communities that had been told, often without words, that their voices were peripheral, and he made a credible case that they were not. That included explicitly naming gay and lesbian Americans as part of the Rainbow Coalition and publicly advocating for action on HIV and AIDS at a moment when most national political leaders remained silent.

The coalition did not ask people to set aside their identities in the name of unity. Rather it insisted that unity and difference could coexist; that the shared stakes could be the basis for shared power.

The results were significant. In 1984, Jackson helped register over a million new voters and won roughly 3.5 million primary votes. Those newly registered voters contributed to Democrats retaking the Senate in 1986. By 1988, he had helped register two million more voters, won seven primaries, briefly led the delegate count, and secured nearly seven million votes.

Jackson never won the nominations. But he did not have to for the coalition to matter. As Illinois state lawmaker Emanuel Welch later stated: “We don’t have Barack Obama as president without Jesse Jackson running in 1984 and 1988.”

The principles still hold

The Rainbow Coalition’s core insight was straightforward: unity does not require sameness.

This runs against two instincts that shape much of today’s mainstream political culture. The first is fragmentation, the retreat into ever-narrower identity-based silos, where coalition feels impossible because difference feels too large to bridge. The second is forced consensus, pressure to minimize differences in the name of unity, which almost always benefits those who already hold power.

The Rainbow Coalition offered a third path. Differences were acknowledged openly, not smoothed over, and the shared stakes became the basis for shared power.

In particular, Jackson’s legacy offers three practical lessons for today’s leaders:

- Start with shared material realities as abstract appeals to unity rarely hold. What does endure is a clear-eyed recognition of common stakes such as economic security, access to opportunity and the experience of being genuinely heard.

- Design for inclusion rather than assume it. The Rainbow Coalition did not emerge by accident; it required intentional outreach, deliberate structure and the willingness to sit with difference rather than rush past it.

- Treat differences as a resource. Coalitions that bring together distinct experiences and perspectives tend to be more resilient than those that achieve cohesion through uniformity. The goal is not consensus on everything, but enough shared purpose to act together on what matters most.

The Rainbow Coalition did have real tensions. It did not hold together perfectly, and Jackson’s campaigns were not without controversy.

But the model, the deliberate choice to organize across difference rather than within it, outlasted the campaigns. In short, its legacy is simple: unity is not something you find; it is something you build.

Why it matters now

Today, polarization is not only cultural; it is structural.

Economic inequality concentrates power in fewer hands and declining civic institutions reduce the spaces where difference can be negotiated. Meanwhile, misinformation accelerates distrust, and distrust makes collective action harder. When polarization compounds in this way, it becomes more than a political problem. It is a governance problem, a resilience problem and ultimately an economic one.

Moreover, this is not only an American story. From Europe to sub-Saharan Africa to Southeast Asia, the same pattern holds: when economic insecurity coincides with political exclusion, fractures deepen. The question of how to build durable coalitions across differences is one every society is being asked to confront.

The Rainbow Coalition did not resolve these structural forces; no single initiative could. But it offers something today’s leaders urgently need: a real-world demonstration that broad, inclusive coalitions are achievable even in periods of deep division, and that building them is, above all, a deliberate choice.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Parity and Inclusion

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Civil SocietySee all

Ginelle Greene-Dewasmes

February 20, 2026