Why the US foreclosure crisis was not just a subprime event

Many studies of the housing market collapse of the last decade, and the associated sharp rise in defaults and foreclosures, focus on the role of the subprime mortgage sector. Yet subprime loans comprise a relatively small share of the U.S. housing market, usually about 15 percent and never more than 21 percent. Many studies also focus on the period leading up to 2008, even though most foreclosures occurred subsequently. In A New Look at the U.S. Foreclosure Crisis: Panel Data Evidence of Prime and Subprime Borrowers from 1997 to 2012 (NBER Working Paper No. 21261), Fernando Ferreira and Joseph Gyourko provide new facts about the foreclosure crisis and investigate various explanations of why homeowners lost their homes during the housing bust. They employ microdata that track outcomes well past the beginning of the crisis and cover all types of house purchase financing—prime and subprime mortgages, Federal Housing Administration (FHA)/Veterans Administration (VA)-insured loans, loans from small or infrequent lenders, and all-cash buyers. Their data contain information on over 33 million unique ownership sequences in just over 19 million distinct owner-occupied housing units from 19972012.

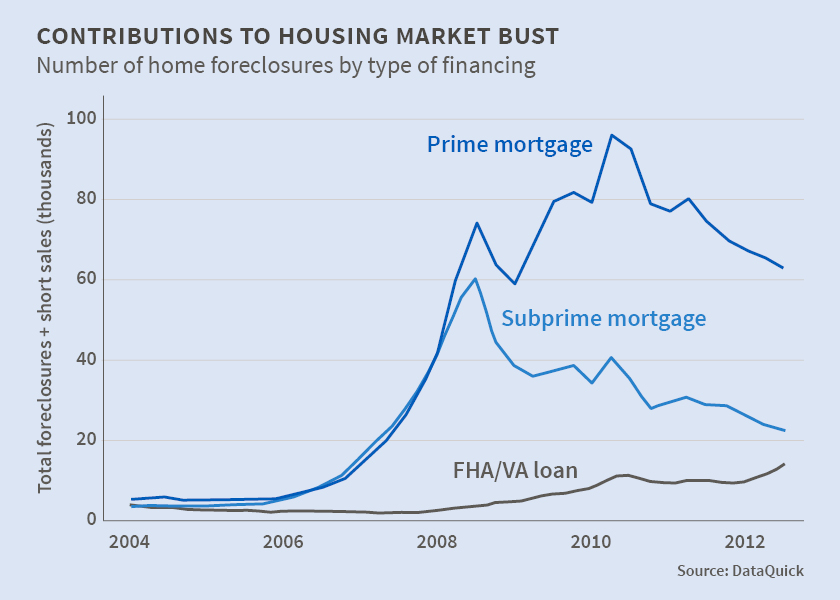

The researchers find that the crisis was not solely, or even primarily, a subprime sector event. It began that way, but quickly expanded into a much broader phenomenon dominated by prime borrowers’ loss of homes. There were only seven quarters, all concentrated at the beginning of the housing market bust, when more homes were lost by subprime than by prime borrowers. In this period 39,094 more subprime than prime borrowers lost their homes. This small difference was reversed by the beginning of 2009. Between 2009 and 2012, 656,003 more prime than subprime borrowers lost their homes. Twice as many prime borrowers as subprime borrowers lost their homes over the full sample period.

The authors suggest that one reason for this pattern is that the number of prime borrowers dwarfs that of subprime borrowers and the other borrower/owner categories they consider. The prime borrower share averages around 60 percent and did not decline during the housing boom. Although the subprime borrower share nearly doubled during the boom, it peaked at just over 20 percent of the market. Subprime’s increasing share came at the expense of the FHA/VA-insured sector, not the prime sector.

The authors’ key empirical finding is that negative equity conditions can explain virtually all of the difference in foreclosure and short sale outcomes of prime borrowers compared to all cash owners. Negative equity also accounts for approximately two-thirds of the variation in subprime borrower distress. Both are true on average, over time, and across metropolitan areas.

None of the other ‘usual suspects’ raised by previous research or public commentators—housing quality, race and gender demographics, buyer income, and speculator status—were found to have had a major impact. Certain loan-related attributes such as initial loan-to-value (LTV), whether a refinancing occurred or a second mortgage was taken on, and loan cohort origination quarter did have some independent influence, but much weaker than that of current LTV.

The authors’ findings imply that large numbers of prime borrowers who did not start out with extremely high LTVs still lost their homes to foreclosure. They conclude that the economic cycle was more important than initial buyer, housing and mortgage conditions in explaining the foreclosure crisis. These findings suggest that effective regulation is not just a matter of restricting certain exotic subprime contracts associated with extremely high default rates.

This article is published in collaboration with The National Bureau for Economic Research. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Les Parker is a writer for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Social Protection

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Marielle Anzelone and Georgia Silvera Seamans

October 31, 2025