Is Japan really in recession?

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Economic Progress

This article is published in collaboration with The Washington Post.

Japan’s economy is shrinking, but it is not in a recession—at least not if that word has any meaning at all.

Well, other than the fact that technically it is. Japan’s gross domestic product just contracted for the second quarter in a row, which, yes, is the rule of thumb we use to define a recession. That has been enough for the usual suspects to crow that Japan’s attempt to jumpstart growth by printing money and deregulating its economy, what is known as “Abenomics,” has failed. But if this is really a recession, it is the strangest one in history. Unemployment, after all, is still only 3.4 percent. That is a whopping … tenth of a percentage point higher than it was six months ago. The reality is that, even in the best of times, Japan’s economy can’t grow much anymore. So it doesn’t mean that it’s the worst of times just because it’s slightly shrinking. That only means that things are normal — and maybe even good.

Now, the simple story is that Japan’s population is decreasing, so its workforce is too, which makes it hard for its economy not to do so as well. That’s because GDP is really the result of two factors—how many people are working, and how productive those people are—and you can’t just wave a magic wand, or, a little more realistically, pull a policy lever, to make the latter go up to offset the former going down. The upshot is that the Bank of Japan thinks the country’s trend growth rate has fallen to “around 0.5 percent or lower.” It doesn’t take much to get from there to negative territory. A bad export or inventory number will do the job. That’s how you get four “recessions” in five years.

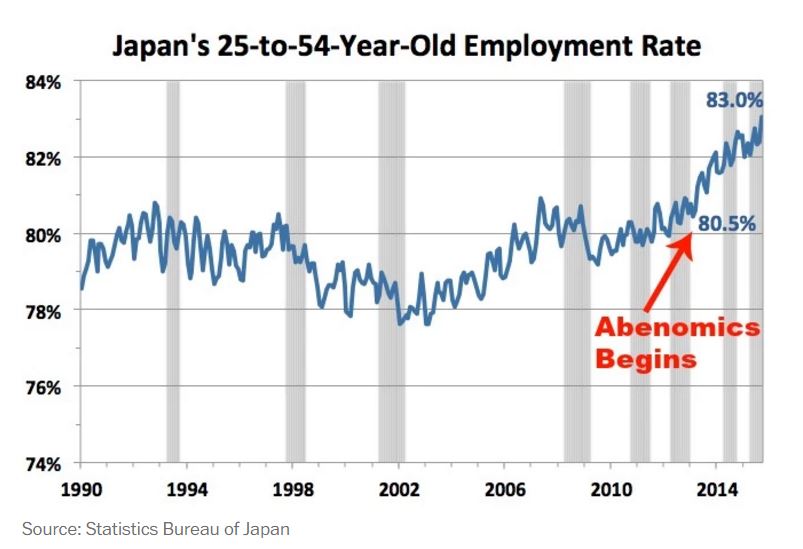

In the real world, though, it’s been more like one. The r-word just doesn’t seem appropriate when everyone who wants a job can find one. Indeed, as you can see above, Japan’s share of working-age adults who are, in fact, working has shot up from 80.5 percent when Abenomicsbegan to 83 percent today, two recessions notwithstanding. As point of comparison, it’s only increased from 75.9 to 77.2 percent in the United States during that time. This is an economy firing on all cylinders—there just aren’t that many of them now that so many Japanese people are hitting their golden years.

The question, then, is what we want to talk about when we talk about recessions. Is it bad demographics or a bad economy? The way we define things now says that both count as a “recession.” Now, this wasn’t a problem until the past 20 years or so when Japan’s workforce started shrinking. But since then, Japan has turned, well, Japanese, and the rest of the rich world has too, with low-to-negative labor force growth of their own. That means that “recessions” won’t just tell us when the economy has hit a turning point, but rather when it’s hit a bump in the road. That’s a little less than useful. If we want to make it more so, as the Financial Times’ Robin Harding points out, we need to look at how the economy is doing relative to how we’d expect it to do. Maybe, as he argues, that means redefining a recession from two quarters of negative growth to two quarters of growth at least 2 percentage points below trend—which, in Japan’s case, would mean -1.5 percent. Or maybe it means looking at when GDP per working-age person starts to decline. In any case, though, the idea is the same: looking past the demographics and at the economy itself.

If the word “recession” is going to tell us what we need to know, it has to be able to distinguish between an economy that’s shrinking because retirement-age people don’t want jobs, and one that’s shrinking because working-age people can’t find jobs. Otherwise, we’ll keep hearing how Japan’s 3.4 percent unemployment is a failure since the country has a lot of old people.

It isn’t. Not even close.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Matt O’Brien is a reporter for the The Washington Post Wonk Blog.

Image: Businessmen walk behind a Japanese national flag at a convention centre. REUTERS/Toru Hanai.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Economic ProgressSee all

Joe Myers

April 12, 2024

Joe Myers

April 5, 2024

Pooja Chhabria

March 28, 2024

Kate Whiting

March 28, 2024

Joe Myers

March 28, 2024

Andrea Willige

March 27, 2024