Are we sleepwalking into geopolitical turmoil?

The world is at risk of sleepwalking into a future of widening chaos, says Espen Barth Eide. Image: REUTERS/Rafael Marchante

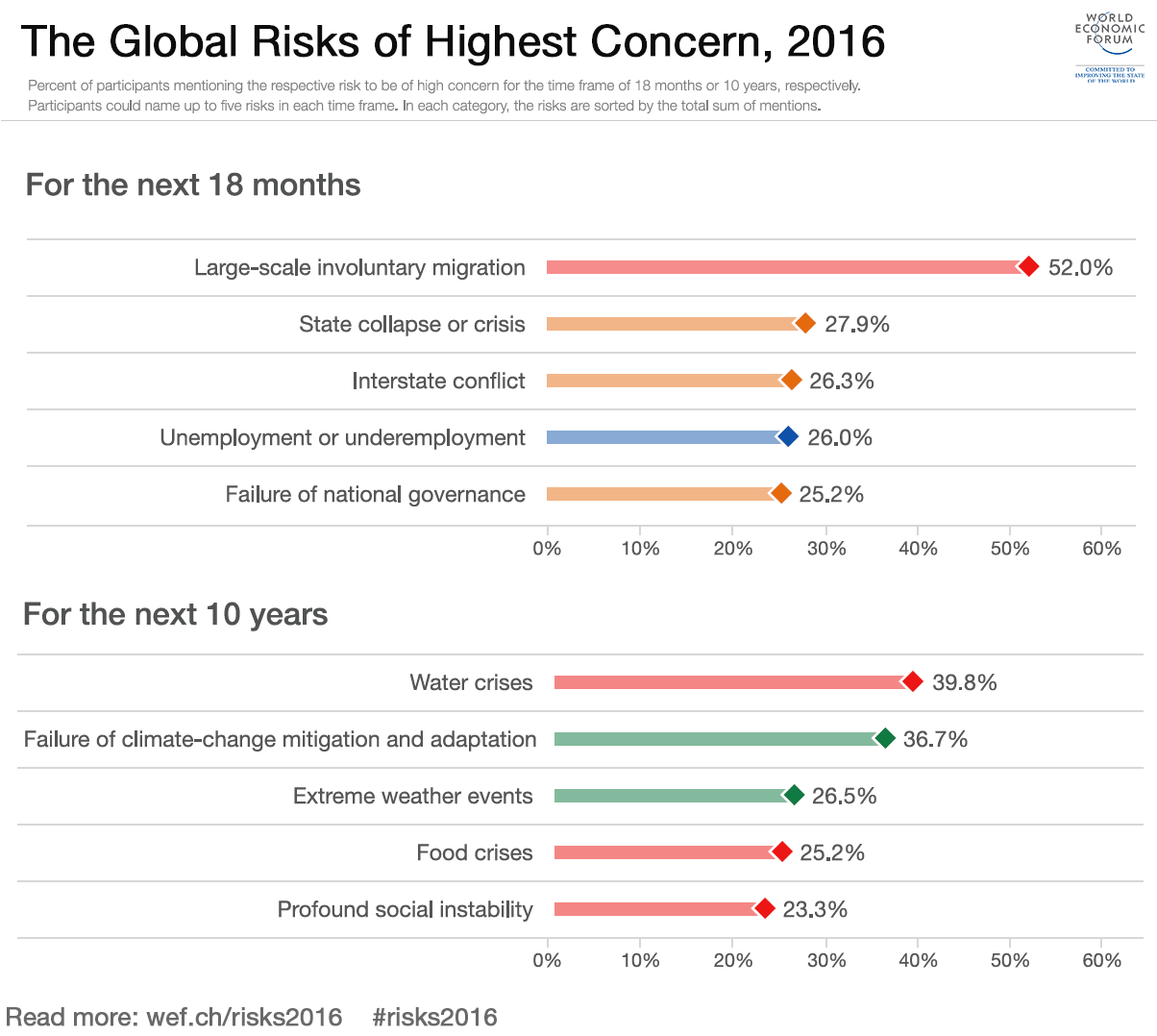

Without a concerted effort to properly address current trends, the world is at risk of sleepwalking into a future of widening chaos with growing danger of interstate conflict. This is the conclusion of a year-long review of global risks, The Global Risks Report 2016, being presented today in London. Geopolitical risk is among the top concerns, but it is the convergence of drivers at different levels – national, regional and global – that threatens to overwhelm existing institutions, and should push us to engage a wider range of stakeholders.

Economic and technological change is happening at a pace that leaves most political and regulatory systems unable to cope. This spurs dissatisfaction with leaders and increasing polarization in society, already weakened by a steep fall in social cohesion and trust. Trust is a fundamental element of social capital, and when it wanes, it negatively affects all aspects of society. Loss of trust results in part from a steady increase in inequality, undermining the feeling essential to the fabric of society of citizens being “in the same boat”.

Downbeat perception of future economic opportunity aggravates grievances, now also in many of the economies that only recently were labelled as “emerging”. Polarization and growing populism forces leaders to take rather ill-advised, short term measures that may give the appearance of “doing something” without really tackling protracted crises at their roots.

Individuals increasingly feel disengaged from traditional structures of power, but strongly engaged through new forms of participation and voice, but in ways that do not necessarily foster shared understanding in society.

The conflicts in Syria and Iraq show how today’s wars are not confined to the battlefront itself. They are “glocal” in the sense that while most of the fighting takes place in a specific region, accompanying terrorist attacks can happen anywhere. Sophisticated recruitment campaigns and social media based information warfare has become genuinely global, with fighters from over 100 countries involved in Syria and Iraq. The allure of joining the battle, for ideological or personal reasons, is just a click away from a teenager’s computer somewhere in a European city. Intelligence services around the world are struggling to cope with a new reality, challenged by everything from well-organized, stealthy groups to self-radicalized “lone wolves”. Three years after the Snowden revelations, the debate on privacy vs. security has been slow to move on from recriminations to the search for practical solutions that command broad-based support.

Cohesion and trust between countries and societies are also under threat. In its most extreme form, this trend may lead to successful calls for withdrawal from an integrated and interlinked world, creating the 21st Century equivalent of medieval “walled cities” that offer the few a sense of security and order, protecting them from the “sea of disorder” on the outside. For instance, the disjointed political debacle over how to manage the reality of people on the move, while not primarily a European phenomenon, has led to strong demands to undo some of Europe’s primary successes of integration, like the Schengen open borders agreement. A gradual dis-integration of Europe would not only be a regional drama, it would, if it happened, have severe implications for global norms and joint aspirations.

This lack of trust and cohesion is also a factor in the development of “hybrid” war. Adversaries – be they states or non-state actors – exploit popular mistrust of government in the design of information operations deployed through conventional media channels as well as more sophisticated campaigns to influence individuals directly via social media. Asymmetric, ambiguous, grey zone, non-linear – these have become the default mode of conflict between major powers seeking to keep their rivalry below the threshold of what is legally defined as "war".

With nuclear powers upgrading their delivery systems, confirming their continued emphasis on the ultimate tool of deterrence, such deniable or indirect ways to influence events, including the use of proxy forces, are gradually becoming the norm. The face of warfare itself is changing. Aversion to outright conflict is also a factor in the rise of geo-economics, or the use of economic relations, sanctions, trade regimes and potentially even means of payment for the purpose of geopolitical rivalry.

The implications for the infrastructure of the global economy are highlighted by the fact that every conflict today is also a cyber-conflict. Cyberspace has become a domain of warfare, on pair with land, sea, air and space. In cyberspace, however, the attacker gets an advantage that he would not have in the physical world, as distance and early warning becomes largely irrelevant. Possibly, globalization has contributed to new modes of conflict that, if left unchecked, could bear the seeds of its destruction.

For some time, the World Economic Forum has warned against globalization going into reverse. The sense of the first post-Cold War decades was that economy finally was becoming open and global, free of the geopolitical lid imposed by great powers. This assumption is again challenged. We see new institutions emerge, driven by new actors, at times complementing, at times challenging the established order. Only time will tell if this is a good or a bad development.

We could see it as a trend towards a net of interlinked regional systems coalescing around regional hegemons, displacing a unified, global economic order, but still sustained by some form of overall agreement. But it could also be read as an early indication that we are transiting into a future global system not so much built on a shared set of values, but rather on tacit understanding of each other’s interests and consensus on the lowest common denominators.

Last year's edition of the Global Risk Report featured the increase of fragility and disintegration on the one hand, and the return of strategic competition between strong and well-organized states on the other. Both trends strengthened in 2015, at times merging into a perfect storm like the one we are now observing in the Middle East: the conflicts in Syria, Iraq and Yemen, to name a few, have local, regional and global dimensions. Regional players, like Iran and Saudi Arabia, compete over the future order of the region. Major global players are simultaneously competing and cooperating, at times engaged on opposing sides in the battle but also at times seeking to forge diplomatic compromises.

This gloomy picture, however, is not a given. The array of technological advances that, when combined, takes us into the Forth Industrial Revolution – a main theme of this year’s Annual Meeting in Davos – hold out the promise of new solutions to old problems. In principle, we are living in a world of almost endless opportunity; with phenomenal advances in health, sustainable energy and economic possibilities. Without effective governance and direction, however, the Fourth Industrial Revolution could also enhance the sense of deprivation and societal alienation. Existing modes of governance seem largely unable to deal with the complex challenges or to fully reap the opportunities available with dedication, foresight and mutually beneficial solutions.

A broad, shared understanding of global trends, across societal sectors, and a will to collectively think through how to deal with them is urgently needed in order to prevent further deterioration and to stake out a better course. Putting these issues on top of the agenda of the Annual Meeting in Davos next week is one attempt to contribute to this global conversation and to inspire collective action.

The Global Risks Report 2016 is available here.

Author: Espen Barth Eide, Head of Geopolitical Affairs, Member of the Managing Board, World Economic Forum

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Global Risks

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Global RisksSee all

Allison Shapira

November 14, 2025