How women are turning the page on literary sexism

Unfair share ... male bylines have traditionally dominated the literary pages – but this is changing Image: REUTERS/Toby Melville

“Crippled, creepish, fashionable, frigid” – an unsavoury volley of adjectives from the pen of Norman Mailer, Pulitzer-winning author and American cultural icon. Their target: the writing capabilities of female authors.

Though they were written in 1959, the assumptions contained in Mailer’s words haven't gone out of date. It was as recently as 2011 that author VS Naipaul lashed out at the “feminine tosh” produced by female novelists: "I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not. I think it is unequal to me," he said.

Dismissive opinions of women’s literary ambitions are no mere anomaly: quite the opposite, they appear to be part of what Virginia Woolf called the dominance of “masculine values” in intellectual life. Three-quarters of a century after her death, men still take up a disproportionate amount of space on the pages of literary publications – whether as authors, reviewers, protagonists within novels or the winners of book awards.

It’s a fact backed up by the findings of a survey by Vida, an American organization that tracks the number of women and men in the publishing world both doing the reviewing and being reviewed. In 2011, its first year of counting, the survey found that only 16% of the reviewers at the London Review of Books were women, and only 26% of the authors reviewed. At the New York Review of Books, only 21% of reviews were by women.

A happy ending?

The good news is that this may be changing. Vida’s latest survey (2015) has found that the number of female writers and reviewers in some publications is creeping up. The Boston Review has been singled out for particular applause: last year more than half of the reviews and the books reviewed in the publication were by women. Overall, women made up 46% of the pie, the highest percentage seen in the six years since Vida started counting.

Vida's work has won praise from female authors. Bestselling novelist Jodi Picoult said of the 2012 survey: "I don't know how to even the odds for female authors except to thank Vida for reinforcing what many readers had a gut feeling about; and reminding the editors of these book review institutions: We are well aware of the gender gap you've helped to create; now we challenge you to help fix it."

Novelist Jennifer Weiner, who once accused the New York Times of favouring “its literary darlings, who tend to be dudes with MFAs”, was optimistic about the impact of Vida's annual count: "Readers and writers being vocal and persistent have made editors take a hard look at those pie charts and try to do better,” she told the Guardian.

A new chapter

How can the survey build on its success? One suggestion, by author Nicola Griffiths, would be to expand its scope to the gender of fictional protagonists. Griffiths carried out a study of six major book awards over 15 years, and found that a literary novel is more likely to win a prize if the central character is male.

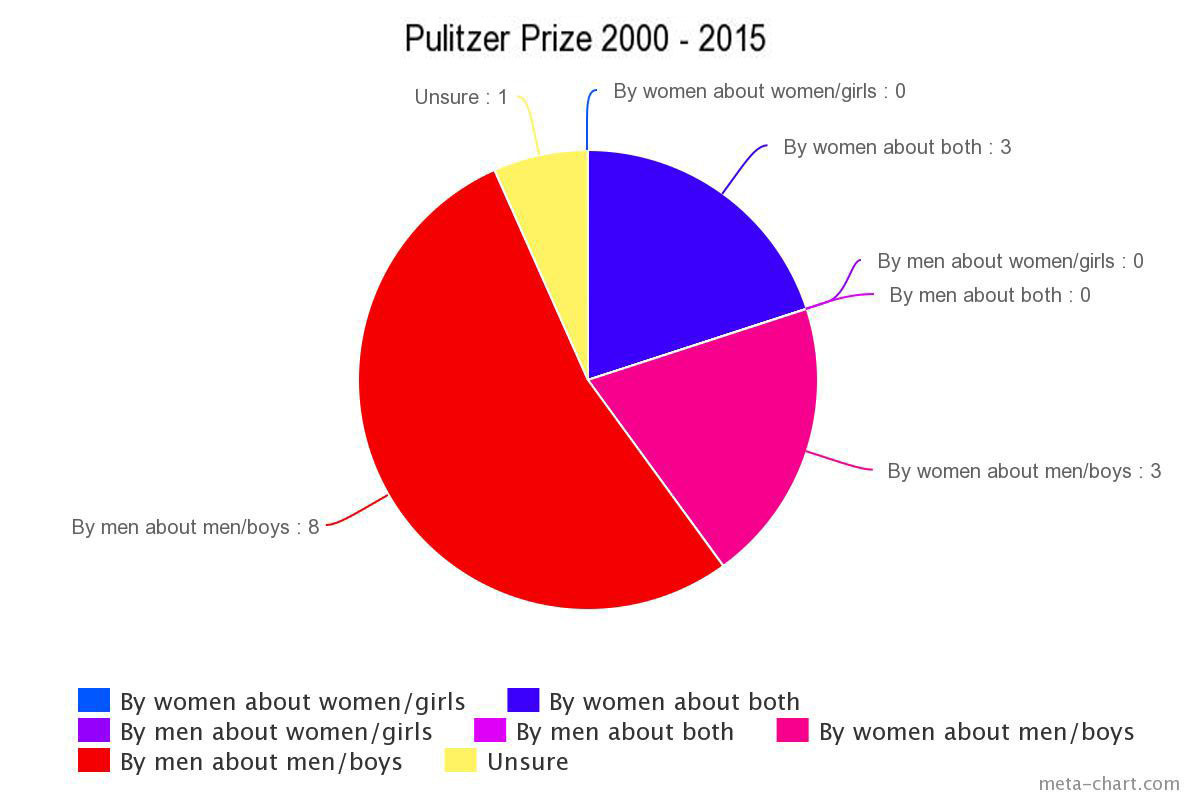

The most dramatic statistics came from studying the Pulitzer prize, where between the years 2000 and 2015 the overwhelming majority of prize-winners were male authors who wrote about male characters. Not one of the 15 award-winning books was written wholly from the point of view of a woman or girl. “Women seem to have literary cooties,” wrote Griffith in a piece outlining her data.

Vida is in fact expanding its remit: the 2015 edition surveyed for the first time the race, ethnicity, sexual identity and ability of its female writers. It found, perhaps unsurprisingly, that the best represented women were straight, white and able-bodied.

Vida’s chair, Amy King, explains that examining female writers according to their demographic identities could reveal valuable information about why certain groups are underrepresented. “In future years, we hope to refine our categories so that we can accurately link categories and their impact on women writers’ reception in the literary landscape,” she says.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Values

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Sebastian Reiche

November 19, 2025