Nuclear weapons test: what's the damage to people and places?

Decades later, nuclear test zones are still uninhabitable

Image: Reuters/Gleb Garanich

Stay up to date:

Nuclear Security

On 9 September, North Korea confirmed it had carried out its fifth test of a nuclear bomb.

The first data on the test came from the US Geological Survey, where monitors detected a 5.3 magnitude earthquake. The epicentre of the quake was located close to North Korea’s nuclear testing site at Punggye-ri in the north-east of the country, close to the border with China.

More powerful than the Hiroshima bomb

Scientists were quick to label the blast as the most powerful North Korea has ever achieved. Jeffrey Lewis of the California-based Middlebury Institute of International Studies said: "That's the largest DPRK test to date, 20 to 30 kilotonnes at least. Not a happy day."

With the explosive power of up to 30 thousand tonnes of TNT, the latest North Korean warhead was more powerful than the bomb dropped by the United States on Hiroshima.

The Little Boy class of bombs that devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki were never detonated in tests. But, as this interactive infographic shows, there have been more than 2,000 nuclear weapons tests since the end of the Second World War.

These are five of the most infamous nuclear test sites.

Bikini Atoll

The first peacetime detonation of a nuclear bomb happened on Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean in 1946. In total, more than 20 tests were carried out on the atoll. A huge hydrogen bomb, code-named Castle Bravo, was detonated in 1954. It was 1,000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb.

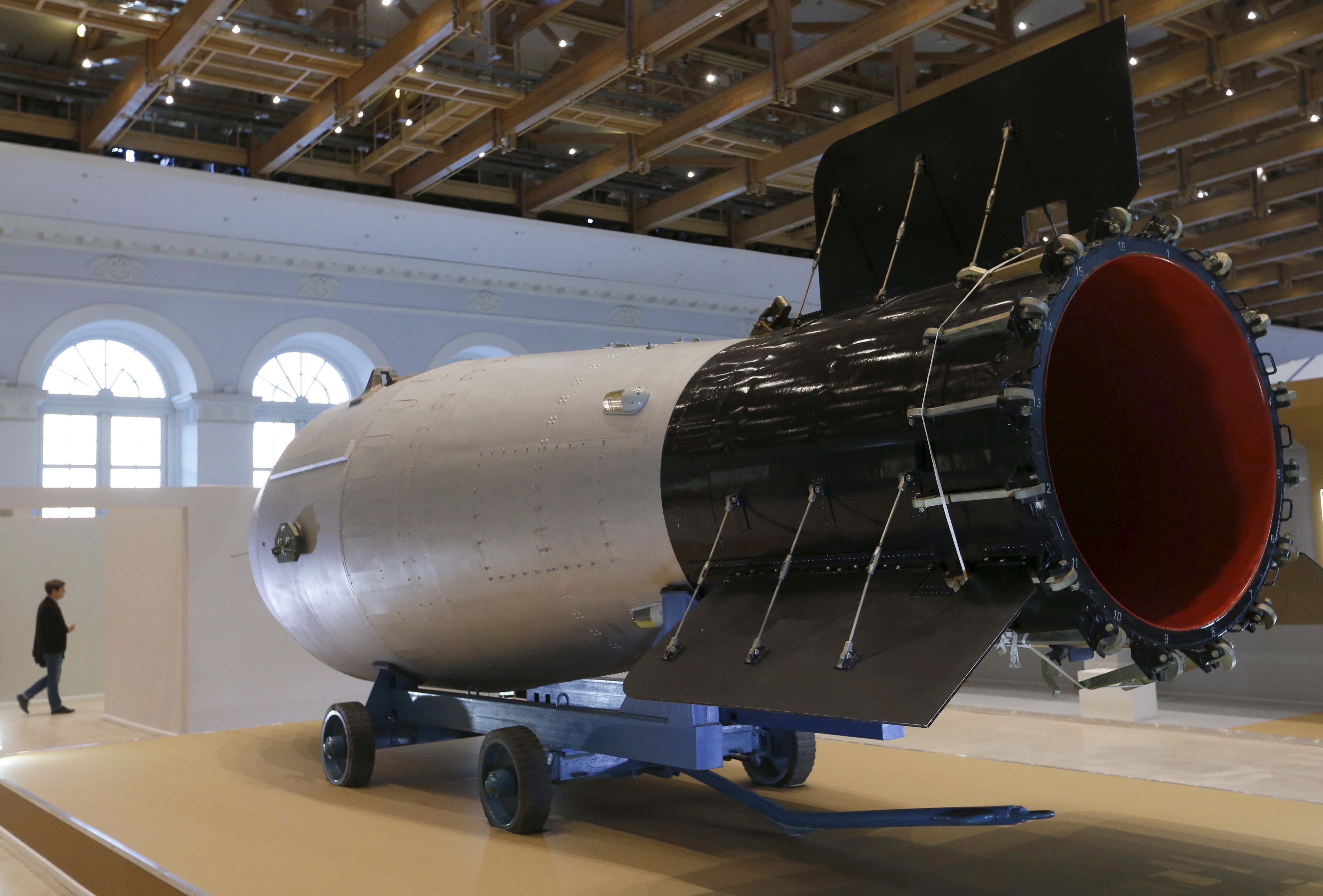

Novaya Zemlya

This remote island in the Arctic Circle was the site of the world’s biggest nuclear detonation.

The Tsar Bomb caused a 100 megaton explosion in 1961. The last test at Novaya Zemlya took place in 1991.

Kiritimati

Once known as Christmas Island, this is one of the most remote places on Earth. It’s the only test site to have been used by two countries. The British tested hydrogen bombs on Kiritimati in 1957 and 1958. When they abandoned the site, the US used it to detonate 22 nuclear devices.

Semipalatinsk

Russia’s first nuclear device was detonated here in 1949. It began a process that included 456 nuclear explosions. Semipalatinsk is actually in Kazakhstan, and after the collapse of the Soviet Union the site was returned the Kazakhs.

Nevada Test Site

Known as the most nuked place on Earth, the Nevada Test Site was used for almost 1,000 nuclear tests between 1951 and 1992. The site covers 3,500 kilometres of the Nevada desert to the north-west of Las Vegas.

A devastating legacy

The human and environmental devastation caused by decades of nuclear testing is still being felt today. The people of Bikini Atoll were told they would have to leave the island for just three months before it would be safe for them to return home. More than 60 years after the detonation of the Castle Bravo bomb, the island is still too dangerous to live on.

The safe level of radiation set by the Republic of the Marshall Islands and the US is 100 millirems per year. In June 2016, researchers from Columbia University reported levels as high as 639 millirems per year and an average of 184 millirems. The researchers compared those readings with levels in New York’s Central Park, which showed just 9 millirems per year.

The nuclear fallout

Such severe nuclear contamination is created in fractions of a second. When a nuclear bomb explodes underground, the rock surrounding the device is vaporized. Rock lying further from the bomb is melted as temperatures rise by several million degrees. In many cases, the ground above collapses into the molten cavity, allowing radiation to spread into the atmosphere and surrounding environment.

But many of the early tests were carried out above ground. There was no attempt at containment. It’s estimated that hundreds of thousands of people living within 80km of Russia’s Semipalatinsk test site were exposed to high levels of radiation.

The website of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty states that the Semipalatinsk region has the lowest "official" cancer statistics in Kazakhstan. It goes on to report that local doctors believe that at least 60,000 people have died from radiation-induced cancers. More than half a million people who were affected by radiation now receive disability allowances from the Kazakh authorities.

Where nuclear explosions are contained below ground, the outcomes for the test site can be less devastating. The Tatum Dome test site in Lamar County, Mississippi was used to test two nuclear devices in the 1960s. Locals reported the ground undulating like liquid as a result of the blasts. A 2015 report by the US Department of Energy shows the site was left with two underground melt cavities but no nuclear material escaped into the wider environment.

From nuclear tests to nature reserve

The surface is now considered safe for humans to visit but nobody is allowed to live there. Growing food on the land is also banned and the government continues to monitor radiation levels in the groundwater. The land is now a nature reserve.

The North Korean legacy?

North Korea’s latest nuclear test has escalated political and military tensions in the region and beyond. The secretive nature of the DPRK will mean we may never fully know how many people are at risk from the nuclear tests being carried out. What we do know is that the human and environmental impact of the tests will last for decades or even centuries to come.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

Elena Raevskikh and Giovanna Di Mauro

July 23, 2025

Arunabha Ghosh and Jane Nelson

July 22, 2025

Sebastian Buckup and Beth Bovis

July 10, 2025