Imagine: we're in a recession. What does the Fed do with interest rates?

The US Federal Reserve predict a hike in interest rates. Image: REUTERS/Gary Cameron

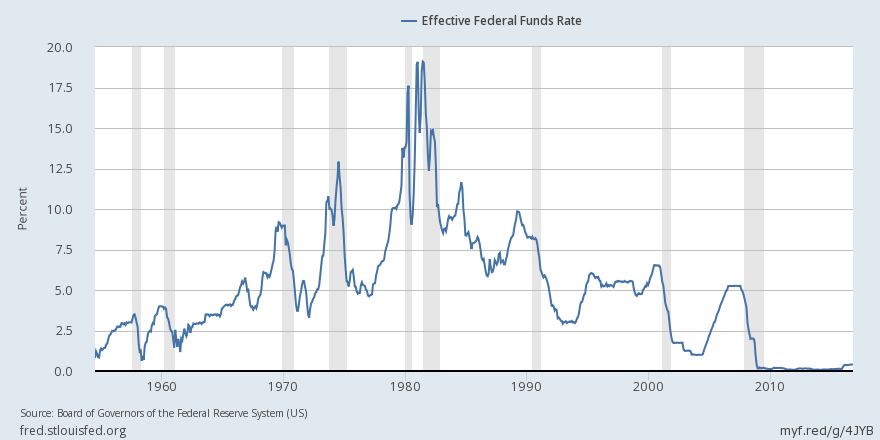

Markets nowadays are fixated on how high the US Federal Reserve will raise interest rates in the next 12 months. This is dangerously shortsighted: the real concern ought to be how far it could cut rates in the next deep recession. Given that the Fed may struggle just to get its base interest rate up to 2% over the coming year, there will be very little room to cut if a recession hits.

Fed chair Janet Yellen tried to reassure markets in a speech at the end of August, suggesting that a combination of massive government bond purchases and forward guidance on interest-rate policy could achieve the same stimulus as cutting the overnight rate to minus 6%, were negative interest rates possible. She might be right, but most economists are skeptical that the Fed’s unconventional policy tools are nearly so effective.

There are other ideas that might be tried. For example, the Fed could follow the Bank of Japan’s recent move to target the ten-year interest rate instead of the very short-term one it usually focuses on. The idea is that even if very short-term interest rates are zero, longer-term rates are still positive. The rate on ten-year US Treasury bonds was about 1.8% at the end of October.

That approach might work for a while. But there is also a significant risk that it might eventually blow up, just the way pegged exchange rates tend to work for a while and then cause a catastrophe. If the Fed could be highly credible in its plan to hold down the ten-year interest rate, it could probably get away without having to intervene too much in markets, whose participants would normally be too scared to fight the world’s most powerful central bank.

But imagine that markets started to have doubts, and that the Fed was forced to intervene massively by purchasing a huge percentage of total government debt. This would leave the Fed extremely vulnerable to enormous losses should global forces suddenly drive up equilibrium interest rates, with the US government then compelled to pay much higher interest rates to roll over its debt.

The two best ideas for dealing with the zero bound on interest rates seem off-limits for the moment. The optimal approach would be to implement all of the various legal, tax, and institutional changes needed to take interest rates significantly negative, thereby eliminating the zero bound. This requires preventing people from responding by hoarding paper currency; but, as I have explained recently, this is not so difficult. True, early experimentation with negative interest-rate policy in Japan and Europe has caused some disenchantment. But the shortcomings there mostly reflect the fact that central banks cannot by themselves implement the necessary policies to make a negative interest rate policy fully effective.

The other approach, first analyzed by Fed economists in the mid-1990s, would be to raise the target inflation rate from 2% to 4%. The idea is that this would eventually raise the profile of all interest rates by two percentage points, thereby leaving that much extra room to cut.

Several central banks, including the Fed, have considered moving to a higher inflation target. But such a move has several significant drawbacks. The main problem is that a shift of this magnitude risks undermining hard-won central bank credibility; after all, central banks have been promising to deliver 2% inflation for a couple of decades now, and that level is deeply embedded in long-term financial contracts.

Moreover, as was true during the 2008 financial crisis, simply being able to take interest rates 2% lower probably might not be enough. In fact, many estimates suggest that the Fed might well have liked to cut rates 4% or 5% more than it did, but could not go lower once the interest rate hit zero.

A third shortcoming is that, after an adjustment period, wages and contracts are more likely to adjust more frequently than they would with a 2% inflation target, making monetary policy less effective. And, finally, higher inflation causes distortions to relative prices and to the tax system – distortions that have potentially significant costs, and not just in recessions.

If ideas like negative interest rates and higher inflation targets sound dangerously radical, well, radical is relative. Unless central banks figure out a convincing way to address their paralysis at the zero bound, there is likely to be a continuing barrage of outside-the-box proposals that are far more radical. For example, the University of California at Berkeley economist Barry Eichengreen has arguedthat protectionism can be a helpful way to create inflation when central banks are stuck at the zero bound. Several economists, including Lawrence Summers and Paul Krugman, have warned that structural reform to increase productivity might be counterproductive when central banks are paralyzed, precisely because it lowers prices.

Of course, there is always fiscal policy to provide economic stimulus. But it is extremely undesirable for government spending to have to be as volatile as it would be if it had to cover for the ineffectiveness of monetary policy.

There may not be enough time before the next deep recession to lay the groundwork for effective negative-interest-rate policy or to phase in a higher inflation target. But that is no excuse for not starting to look hard at these options, especially if the alternatives are likely to be far more problematic.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Financial and Monetary Systems

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Financial and Monetary SystemsSee all

Jaime Magyera

November 13, 2025